Michael E. Krauss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

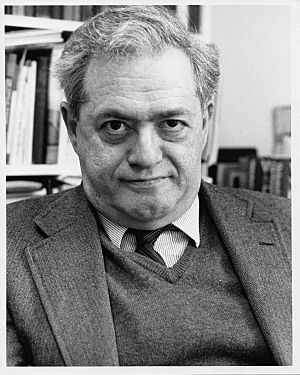

Michael E. Krauss

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 15, 1934 |

| Died | August 11, 2019 (aged 84) Needham, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Linguistics |

Michael E. Krauss (August 15, 1934 – August 11, 2019) was an American linguist. A linguist is a scientist who studies human language. He was also a professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He founded and led the Alaska Native Language Center for many years. Michael Krauss passed away on August 11, 2019, just before his 85th birthday. The Alaska Native Language Archive is named after him.

Krauss was especially known for his work on Athabaskan languages and the Eyak language. The Eyak language sadly became extinct in January 2008. However, he studied all 20 Native languages of Alaska. Many of these languages belong to the Na-Dené and Eskimo–Aleut language families.

Throughout his career, Michael Krauss worked to make people aware of a big problem: endangered languages. These are languages that are at risk of disappearing forever. He encouraged people to record and help bring back languages around the world.

Krauss started working at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in 1960. He led the Alaska Native Language Center from when it began in 1972 until he retired in 2000. Even after retiring, he kept working to document Alaska's Native languages. He also continued to raise awareness about endangered languages globally.

Education and Early Work

Michael Krauss studied at several universities. He earned his first degree from the University of Chicago in 1953. He then received a master's degree from Columbia University in 1955. He also studied in Paris, France. In 1959, he earned his Ph.D. in Linguistics from Harvard University. His Ph.D. research was about the Irish Gaelic language.

After his studies, Krauss did fieldwork in different places. He studied the Irish language in Western Ireland from 1956 to 1958. He also worked with Nordic languages in Iceland and the Faroe Islands from 1958 to 1960.

Saving Alaska's Languages

In 1960, Michael Krauss moved to Alaska. He was very interested in the Native languages of Alaska. He quickly saw that these languages were in danger of being lost. He decided to focus on documenting them. He started with the Lower Tanana language.

Krauss's biggest contribution was his work on the Eyak language. He began this work in 1961. Eyak was already one of the most endangered languages in Alaska. His work was like "salvage linguistics," meaning he worked to save what he could before it was too late. He helped show how Eyak was connected to other languages like Ahtna and Navajo. This helped linguists understand the larger Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit language family.

The Crisis of Endangered Languages

In January 1991, Michael Krauss gave an important speech. He spoke at a conference for the Linguistic Society of America. This speech is often seen as a turning point for the study of languages. It helped focus the field of linguistics on documenting and saving the world's many languages.

His lecture was called "The world's languages in crisis." In it, Dr. Krauss pointed out a serious issue. He said that in the United States, children were learning only a small percentage of the world's remaining languages. This meant many languages were not being passed down to new generations. His work inspired a worldwide effort to document and protect the amazing variety of languages on Earth.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |