Eyak language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eyak |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ʔiːjaːq] | |||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Region | Cordova, Alaska | |||

| Ethnicity | Eyak | |||

| Extinct | January 21, 2008, with the death of Marie Smith Jones | |||

| Language family |

Dené–Yeniseian?

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

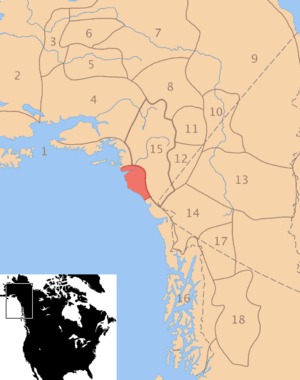

Pre-contact distribution of Eyak

|

||||

|

||||

Eyak was a special language once spoken by the Eyak people. They are a group of indigenous people who lived in south-central Alaska, near the Copper River. The name Eyak comes from a word (Igya'aq) used by the Chugach Sugpiaq people for an Eyak village.

Eyak is closely related to the Athabaskan languages. Together, Eyak and Athabaskan languages form a major part of the larger Na-Dené language family. The only other main language in this family is Tlingit.

Many Tlingit place names along the coast of Alaska actually came from Eyak words. These names often don't make sense in Tlingit, but old stories explain their Eyak meanings. This suggests that the Eyak language was once spoken over a much larger area than when Europeans first arrived. This matches the stories told by both the Tlingit and Eyak people about how they moved around the region long ago.

Contents

The Eyak Language Today: A Story of Revival

The last person who spoke Eyak as their first language was Marie Smith Jones. She was born on May 14, 1918, and passed away on January 21, 2008, in Cordova.

The Eyak language started to disappear for several reasons. One big reason was the spread of the English language. Also, the Tlingit people moved north a long time ago. This led to more people speaking Tlingit instead of Eyak along the Alaskan coast. The Eyak language also faced pressure from the Alutiiq people to the west and people from the Copper River valley. Over time, Eyak and Tlingit cultures mixed, and many Eyak-speaking groups started using Tlingit. This meant that after a few generations, Tlingit replaced Eyak for most of these mixed groups.

Bringing Eyak Back to Life

In 2010, an interesting story came out about Guillaume Leduey. He was a college student from France who had a surprising connection to the Eyak language. When he was just 12 years old, he started teaching himself Eyak! He used books and audio lessons from the Alaska Native Language Center. Even though he never visited Alaska or met Marie Smith Jones, he learned a lot.

The same month his story was published, Guillaume traveled to Alaska. There, he met Dr. Michael E. Krauss, a famous language expert from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Dr. Krauss helped Guillaume learn how to pronounce Eyak words correctly. He also gave him more lessons on Eyak grammar and how words are formed.

In 2011, Guillaume came back to Alaska to lead Eyak language workshops. These workshops were held in Anchorage and Cordova. Today, he is considered a fluent speaker, translator, and teacher of Eyak. Even with his fluency, Eyak is still called "dormant." This means there are no native speakers left. On a scale that measures how much a language is used, Eyak is a 9, which means it's dormant. It helps people remember their heritage, but no one speaks it fluently as a first language. Guillaume now helps the |Eyak Language Project from France. He provides lessons and helps create learning materials.

The Eyak Preservation Council also received a grant to create a website. This website is all about saving the Eyak Language. Other money helps support the yearly Eyak Culture Camp, which happens every August in Cordova. The project offers many ways to learn the language. These include workshops where you can speak only Eyak, an online dictionary with sound clips, and online lessons.

In June 2014, the Eyak Language Revitalization Project launched an online program called "dAXunhyuuga'." This name means "the words of the people."

Eyak's Place in the Language Family Tree

Eyak is part of the Eyak-Athabaskan language family. This family is a branch of the larger Na-Dené group. The Na-Dené group includes Eyak-Athabaskan and Tlingit. Some experts also think the Haida language might be part of this group, but that's still debated.

The Athabaskan family itself is spread across three different areas. There are the Northern Athabaskan languages in Alaska and the Yukon. Then there are the Pacific Coast Athabaskan languages in California and Oregon. Finally, the Southern Athabaskan languages, also called Apache, are spoken mainly in the American Southwest. This group includes the well-known Navajo.

Scientists have studied how the ancient "Proto-Athabaskan-Eyak" language might have sounded. More recently, many linguists (language scientists) have accepted a new idea called Dené–Yeniseian. This idea suggests a link between the Dené languages (which include Eyak and Athabaskan) and the Yeniseian languages from central Siberia. If this idea is proven true, it would be the first confirmed link between languages from the "Old World" (like Asia) and the "New World" (like North America). Another idea, called Dené–Caucasian, has been studied for decades but is much less accepted.

How Eyak Words are Built

Eyak is an agglutinative and polysynthetic language. This means that words are often built by adding many small parts (like prefixes and suffixes) to a main word part (the stem). Imagine building a long train where each car adds a new meaning!

Nouns in Eyak

Most Eyak nouns (words for people, places, or things) don't change their form much. However, words for family members and body parts can have special prefixes added to them. These prefixes show who owns the item. For example, there are prefixes for "my," "your," "his/her/their," "our," and "your (plural)."

Verbs in Eyak

Eyak verbs (action words) are very complex! They can have many prefixes (parts added before the stem) and suffixes (parts added after the stem). There can be up to nine different positions for prefixes before the verb stem and four positions for suffixes after it. Each position can add a different meaning, like who is doing the action, when it happened, or how it happened.

For example, a single Eyak verb could mean something like "I did not tickle your (plural, emphatically) feet." This shows how many pieces can be put together to form one complex word.

Tense, Mood, and Aspect

Eyak verbs also show different moods and aspects. Moods include "optative" (like wishing something would happen) and "imperative" (giving a command). Aspects show how an action happens over time. For example, "perfective" means the action is completed, while "imperfective" means it's ongoing.

How Eyak Sentences are Formed

Most of what we know about Eyak sentences comes from old stories, not everyday conversations. In Eyak, the basic word order is usually Subject-Object-Verb, or SOV. This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the thing the action is done to, and finally the action itself. For example, you might say "Johnny his hand shot" instead of "Johnny shot his hand."

However, many sentences don't follow this exact order. It's more common to find just a Subject-Verb (SV) or Object-Verb (OV) order. A full Eyak sentence can have many parts, including introductory words, the subject, the object, and a complex verb section that includes special words called preverbals.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma eyak para niños

In Spanish: Idioma eyak para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |