Michael Graziano facts for kids

Michael Steven Anthony Graziano (born May 22, 1967) is an American scientist and novelist. He is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Princeton University. His science work focuses on how the brain creates awareness. He has a theory called the "attention schema" theory. This theory explains how brains understand and use the idea of awareness.

His earlier work looked at how the brain monitors the space around the body. It also studied how the brain controls movement in that space. He suggested that the brain's map for movement, called the homunculus, might be different than previously thought. He believes it's more like a map of complex actions. His ideas have been important in neuroscience, but they have also caused some debate. Graziano also writes novels that often have a surrealism or magic realism style. He also creates music, including symphonies.

Contents

Biography

Michael Graziano was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1967. He grew up in Buffalo, New York. He earned his first degree from Princeton University in 1989. He studied psychology there. He then went to MIT for neuroscience from 1989 to 1991. After that, he returned to Princeton University. He finished his advanced degree in neuroscience and psychology in 1996. He has stayed at Princeton University ever since. He worked as a researcher and then became a professor.

Contributions in Neuroscience

Graziano has made important discoveries in three main areas of neuroscience. These areas include how brain cells in primates understand the space around the body. He also studied how the motor cortex controls complex movements. Finally, he explored the possible brain basis of consciousness. These discoveries are explained in more detail below.

Understanding Space Around the Body

In the 1990s, Michael Graziano and Charles Gross studied special brain cells in monkeys. These cells were "multisensory," meaning they reacted to more than one sense. They found a network of brain areas that seemed to understand the space right around the body.

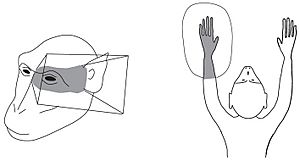

Each of these multisensory brain cells reacted to touch on a specific part of the body. This area was called its "tactile receptive field." The same cell also reacted to things seen or heard near that body part. For example, a cell that reacted to touch on the hand would also react to something seen near the hand. These cells helped the brain know if an object was near or touching a body part. This was true whether the object was felt, seen, heard, or even remembered.

Scientists also found that if they stimulated these cells with electricity, the monkeys would make complex movements. These movements often looked like flinching or blocking actions. If the cells were stopped from working, the monkeys became less likely to flinch. If the cells were made more active, even a small movement toward the face would cause a strong flinching reaction.

Graziano believes these cells form a special brain network. This network helps the brain understand the space around the body. It also helps the brain figure out how safe that space is. This network helps coordinate movements, especially those that involve pulling away or blocking. A small signal from these cells might help avoid a bump. A strong signal could cause a full defensive action.

These "peripersonal" neurons might also explain "personal space." This is the invisible bubble of space around each person. It is a space we like to keep clear of others. These neurons may also be important for the "body schema." This is like an internal model our brain creates of our own body.

How the Motor Cortex Controls Action

In the 2000s, Graziano's lab found new evidence about the motor cortex. The motor cortex is the part of the brain that controls movement. Older ideas, like Penfield's "motor homunculus," suggested it had a simple map of the body's muscles. Graziano's team suggested it might instead contain a map of useful, coordinated actions. These are the actions we use every day.

In their first experiments, Graziano and his team used electrical stimulation on the motor cortex of monkeys. Most past studies used very short bursts of stimulation. Graziano used longer stimulation, about half a second. This matched the typical time a monkey takes to reach and grab something. The longer stimulation caused complex movements involving many body parts. These movements looked like actions the monkeys would naturally do.

For example, stimulating one spot always made the hand close into a grip. It also made the arm bring the hand to the mouth, and the mouth open. Stimulating another spot made the grip open, the palm turn away, and the arm extend. This looked like the monkey was reaching to grab an object. Other spots caused other complex movements. It seemed like the animal's natural actions were mapped onto the brain's surface.

This idea caused some debate because of the longer stimulation method. However, other methods also supported the "action map" idea. For instance, computer models showed that if a monkey's complex movements were arranged on a flat map, similar movements would be close together. This map looked a lot like the known arrangement of the monkey motor cortex.

Graziano suggests that the motor cortex's complex features, like its overlapping maps, might be because it represents many different actions. Each action has its own special needs for control. He believes the "action map" idea helps explain why the motor cortex is divided into different areas. It also explains why these areas are arranged the way they are.

Other scientists have since found similar ways that motor areas are organized in different animals. However, some direct tests of the "movement repertoire" idea have not fully supported it. For example, changing the starting position of a monkey's arm did not change the muscle groups activated by stimulation. This means the movements reached almost the same final position. But the path of the movement was different depending on where the arm started. This suggests that a controlled movement in real life needs many brain areas working together.

The Brain's Basis for Awareness

Since 2010, Graziano's lab has studied how the brain creates consciousness, or awareness. Graziano proposed that special brain systems calculate the feature of awareness. They then assign this feature to other people in social situations. He believes the same system also assigns awareness to ourselves. If this system is damaged, a person's own awareness can be disrupted.

The attention schema theory (AST) tries to explain how a machine that processes information could act like people do. It explains why people insist they have consciousness. It also explains why they describe consciousness in certain ways. AST is now being used in artificial intelligence systems. This is happening through the international Astound project.

The AST idea was partly inspired by two earlier discoveries.

First, certain brain regions are active when people try to understand other people's minds. These regions include the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and the temporoparietal junction (TPJ). These areas are active on both sides of the brain, but especially on the right side.

Second, when these same brain regions are damaged, people can lose awareness of things around them. For example, damage to the TPJ or STS in the right side of the brain can cause hemispatial neglect. This is when a person loses awareness of one side of space.

These two findings led to the idea that awareness might be a feature created by a special brain system. This system partly involves the TPJ and STS. In this idea, the brain can assign awareness to other people when we interact with them. It can also assign awareness to ourselves, which creates our own sense of awareness.

Why would the brain create the feature of awareness and assign it to others? To understand and predict what other people will do, it's helpful to know what they are paying attention to. Attention is how the brain focuses on some signals and ignores others. According to AST, when the brain thinks person X is aware of thing Y, it's actually modeling that person X is paying attention to signal Y. So, awareness is like a "schema" or model of attention. In this theory, the same process can be applied to oneself. Our own awareness is a simplified model of our own attention.

Books

Graziano writes novels for adults under his own name. He writes children's novels using the pen name B. B. Wurge. He uses a different name for children's books so kids don't accidentally pick up his adult novels. His novels have been praised for being original, vivid, and imaginative. His children's book, The Last Notebook of Leonardo, won the 2011 Moonbeam Award.

His books include:

Literary Novels:

- The Love Song of Monkey (2008)

- Cretaceous Dawn (2008)

- The Divine Farce (2009)

- Death My Own Way (2012)

Children's Novels (written under the name B. B. Wurge):

- Billy and the Birdfrogs (2008)

- Squiggle (2009)

- The Last Notebook of Leonardo (2010)

Books on Neuroscience:

- The Intelligent Movement Machine (2008)

- God, Soul, Mind, Brain (2010)

- Consciousness and the Social Brain (2013)

- The Spaces Between Us: A Story of Neuroscience, Evolution, and Human Nature (2018)

- Rethinking Consciousness: A Scientific Theory of Subjective Experience (2019)

Books of Music:

- Three Modern Symphonies (2011)

- Symphonies 4, 5, and 6 (2012)

- Five String Quartets (2012)