Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission facts for kids

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, often called the Sov-Com, was a special government agency in Mississippi. It operated from 1956 to 1977. The Governor of Mississippi was in charge of it.

The commission said its goal was to "protect the state's independence" from the U.S. Federal Government. It also tried to make Mississippi and its system of racial segregation (keeping Black and white people separate) look good. The governor and lieutenant governor were always members of the commission.

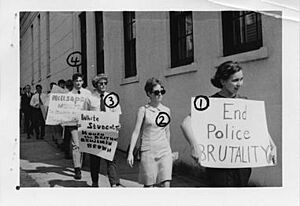

This agency had unusual powers. It could secretly investigate people, ask for official documents, and even act like a police force. During its time, the commission collected information on over 87,000 people. These were people who were involved in, or suspected of being involved in, the Civil Rights Movement. The commission was against this movement. It looked into people's jobs, money, and even their personal relationships. It worked with white officials, police, and businesses to pressure African Americans to stop their activism. For example, they would try to get people fired, evicted from their homes, or have their businesses boycotted.

Why the Commission Was Created

In 1956, James P. Coleman became the new governor. He wanted to stop the federal government from forcing schools to integrate (allow Black and white students to attend together). This was after the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

So, Governor Coleman helped pass a law to create the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission. Its main goal was to keep segregation in place. The commission also claimed it would help improve the state's image for business and tourism. However, it was given special secret powers. It could investigate regular citizens, demand information, and even use police-like actions. All of this was done to stop civil rights activities.

The commission had twelve appointed members. The governor, lieutenant governor, the Speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives, and the state attorney general were also members because of their positions. The governor was the chairman. The commission started with a budget of $250,000 each year.

What the Commission Did

At first, the commission tried to improve Mississippi's image. But when civil rights activism grew, the commission became a secret information-gathering group. It tried to find citizens who might support civil rights, or who seemed to be connected to communists. It also looked for anyone whose activities didn't fit the rules of segregation.

Because of these broad rules, tens of thousands of African Americans and white professionals, teachers, and government workers were put on lists of suspected people. This included people in churches and community groups. The commission secretly joined many major civil rights groups in Mississippi. It even placed office workers in the offices of civil rights lawyers.

The commission told police about planned marches or boycotts. It encouraged police to bother African Americans who worked with civil rights groups. Its agents also tried to stop Black people from registering to vote. They also bothered African Americans who tried to attend white schools.

The commission worked to keep segregation and Jim Crow laws (unfair laws that separated people by race) in place. It also tried to make the state look good. Some of its first employees were a former FBI agent and someone from the state highway patrol. The agency publicly talked about racial harmony. But secretly, it paid investigators and spies to gather information and spread false information.

The commission worked closely with, and sometimes funded, the White Citizens' Councils. These were private groups that supported segregation. From 1960 to 1964, the commission secretly gave $190,000 of state money to the White Citizens Council.

The commission also used its secret information to help Byron De La Beckwith. He was the person responsible for the death of Medgar Evers in 1963. During De La Beckwith's second trial in 1964, a Sov-Com investigator named Andy Hopkins gave information about potential jury members to De La Beckwith's lawyers. The lawyers used this information when choosing the jury.

In 1964, the Sov-Com shared information about civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman. This information went to the people involved in their deaths during Freedom Summer. A commission agent, A.L. Hopkins, met with local law enforcement. He suggested that the disappearance of the three young men was just a trick to get attention.

After Paul B. Johnson Jr. was elected governor, the agency's director, Erle Johnston, expanded its public relations work. He tried to build stronger ties with businesses. He also kept an eye on groups he considered "subversive," like the Congress of Racial Equality, founded by James Farmer. Johnston left the commission in 1968.

End of the Commission and Its Records

In the 1971 state elections, Bill Waller was elected governor, and William F. Winter was elected lieutenant governor. Winter had been against the commission from the start. When they took office, the commission was not doing much work. Both men avoided appointing new members or attending its monthly meetings. They sent representatives instead.

In 1973, the legislature approved money for the commission to continue. But Governor Waller stopped the funding. Lieutenant Governor Winter attended the commission's last meeting in June to confirm that funding was cut. The commission officially closed on June 30.

Six cabinets of the commission's records were given to the Mississippi Secretary of State. They were then stored in a secret underground vault. The law that created the commission was officially canceled in 1977.

There was a big discussion about what to do with the many files about tens of thousands of citizens. Some lawmakers even suggested burning them. After the agency closed, state lawmakers ordered the files to be sealed until 2027 (50 years later). They were moved to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

However, the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) filed a lawsuit to make the records public. In 1989, a federal judge ordered the records to be opened, with some exceptions for people who were still alive. Legal challenges delayed the public release of the records until March 1998.

The court made some rules to protect the privacy of citizens who had been investigated. People in the documents were called "victims" (those who were investigated) or people who worked for the commission or helped it. Since the commission agents had acted illegally and violated people's rights, they were considered to have given up their own privacy rights. Victims had 90 days to decide if they wanted their records sealed, but very few chose to do so.

Once the records were opened, they showed more than 87,000 names of citizens the state had collected information about. Today, these commission records can be searched online. The records also showed the state's involvement in the deaths of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi. The commission's investigator, A. L. Hopkins, gave information about the workers to the commission. This included the car license number of a new civil rights worker. The commission then passed this information to the Sheriff of Neshoba County, who was involved in the deaths.

A similar agency, the Louisiana Sovereignty Commission, operated in Louisiana during the 1960s.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |