New Caledonian rail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New Caledonian rail |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Stuffed specimen | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Cabalus |

| Species: |

C. lafresnayanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cabalus lafresnayanus (Verreaux, J & Des Murs, 1860)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

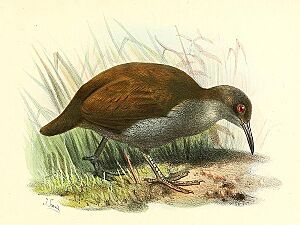

The New Caledonian rail (Cabalus lafresnayanus) is a large, dull-colored bird that cannot fly. It lives only on the island of New Caledonia in the Pacific Ocean. This bird is Critically Endangered, meaning it is very close to disappearing forever. It might even be extinct already. If it still exists, it is one of the rarest and least-known birds in the world.

This rail is about 45 centimeters (18 inches) long. It has dull brown feathers on its back and gray feathers underneath. Its bill is yellowish and curves downwards. The feathers are soft and fluffy, which is why the bird cannot fly. Its wings are also smaller than those of birds that can fly. Since no one has seen this bird since the 1890s, we do not know what its call sounds like or what it does every day. Scientists believe it is a shy bird that lives in woodlands. It might be active at night, or during dawn or dusk.

About the New Caledonian Rail's Name

The scientific name of the New Caledonian rail, lafresnayanus, honors a French bird expert named Frederic de Lafresnaye. For a long time, scientists found it hard to figure out how this bird was related to other birds. This was because there were only a few specimens (dead birds studied by scientists) and its plain look did not give many clues. Also, because it lost the ability to fly, its body changed, making it even harder to tell its family connections.

Scientists once thought it was closely related to the Lord Howe woodhen, another plain-looking bird from an island. They were often grouped together in a large genus called Gallirallus. However, DNA studies later showed that the New Caledonian rail is quite different from many of these birds.

Where Does It Fit in the Bird Family Tree?

Scientists have been trying to understand the New Caledonian rail's place in the bird family tree. It is often placed in a genus called Cabalus, along with the Chatham rail, which is now extinct. However, different DNA studies sometimes show different results about how these birds are related.

What scientists are sure about is that the New Caledonian rail is a very old branch of the Rallini bird group. This group includes many types of rails. The New Caledonian rail's ancestors likely separated from other rail groups millions of years ago. This happened as rails spread across islands in the Pacific.

Life and Disappearance of the Rail

This bird is thought to live in evergreen forests. If any are still alive, they likely moved higher up into the island's mountains. They would have done this to escape animals brought to the island by humans. These animals include wild cats, dogs, and pigs.

The New Caledonian rail was also home to a special kind of louse (a tiny parasite) called Rallicola piageti. This louse was only found on the New Caledonian rail. If the bird is extinct, then this louse is likely coextinct too, meaning it also died out because its host disappeared.

We only know about this mysterious rail from seventeen specimens collected between 1860 and 1890. It is very likely that the wild cats, dogs, and pigs brought by humans caused its extinction. Even though the bird has not been officially seen since 1890, some people reported seeing it in the 1960s and 1984 in the high mountain forests. A search in 1998 did not find any clear proof from hunters or from fieldwork. Still, it is possible that a few of these birds might still be living in very isolated parts of the island.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |