New Churchyard facts for kids

The New Churchyard was a special burial ground in London, England. It was opened in 1569 and used for burials until 1739. During that time, about 25,000 people were buried there! It was created because London's population was growing fast. More places were needed to bury people between the 1500s and 1700s.

Even though it was called a "churchyard," it wasn't connected to a church. From the mid-1600s, it became known as Bedlam or Bethlem burial ground. This was because it was located in the "Bedlam" area, which used to be part of the land of Bethlem Hospital. Today, the remains of this burial ground are under Liverpool Street in the north-east part of the City of London.

This burial ground was open to everyone. People from all parts of society were buried there, especially those who were poor or didn't fit into regular church groups. It was used by people from different religious backgrounds. Many poor people, those who died in London's hospitals and prisons, and even victims of the plague were buried here.

In 1772, the burial ground was turned into private gardens. But in the 1800s and 1900s, during new building projects, the old burials were found again. This happened when Liverpool Street (the road) was built in 1823–24 and when Broad Street railway station was built in 1863–65. More recently, in 1985–87 and 2011–15, archaeologists carefully dug up and studied the site. This was done for the Broadgate development and the Crossrail railway project.

Contents

A Look Back in Time

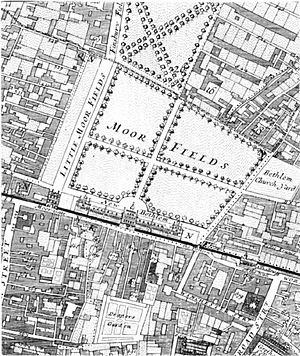

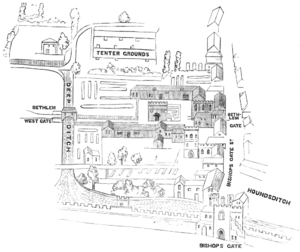

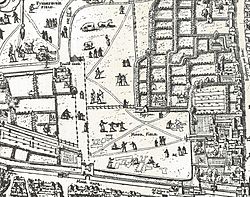

The New Churchyard was located near London's old wall, in an area called Bishopsgate. This is where Broad Street station used to be, and it's now under the western part of Liverpool Street. Before 1569, this spot was an open piece of land on the edge of Moorfields. Moorfields was one of the last open spaces in the City of London.

This land originally belonged to Bethlem Hospital. By the 1500s, it was being used as a garden. After the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1541 (when many religious buildings were closed), the land became part of the City of London Corporation. Just before it became a burial ground in 1569, it was used as a "tenterground." This was a place where cloth was stretched out to dry.

Opening the Burial Ground

By the late 1560s, the City of London Corporation realized London needed a public burial ground. This was especially true during times when many people were getting sick and dying. In July 1569, the Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Rowe ordered the land to be used for burials.

The first person buried there was John Sherbrooke, sometime between January and February 1570. The ground was meant to be "free for the whole Citie to burye in." The only cost was for digging the grave, which was 6 pence. A special pulpit was built in the middle of the ground. Every year, a public sermon was held there on Whit Sunday between 1570 and 1642. The mayor and other important officials were expected to attend.

Closing the Burial Ground

In 1737, new houses called Broad Street Buildings were built next to the burial ground. By this time, the ground was very full of burials. But people kept burying bodies there, even with houses nearby. The residents of Broad Street Buildings complained about the smell and "noxious and pestilential quality" (meaning bad and unhealthy air) coming from the mass graves.

So, on March 1, 1739, the City decided to close the burial ground. They said it was "full of corps" (bodies) and "dangerous to bury any more." They worried about the "noisome steam and stench" (bad smells) that could cause illness. Although some burials continued for a short time, the last person named as being buried there was Mary Burt, who died at 105 years old on April 9, 1738.

The Burial Ground Disappears

In 1762, the City tried to sell part of the burial ground for building. But local residents and the church of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate protested, and the sale was cancelled. In 1772, the burial ground was turned into gardens and yards for the nearby houses. All signs of the burial ground, like monuments and gravestones, were removed from the surface.

Finding it Again

Parts of the burial ground were uncovered during building projects in the 1800s, 1900s, and 2000s. When Liverpool Street was created around 1823–24, workers found hundreds of human bones. Some were reburied, and others were taken away. Charles Roach Smith, an early English archaeologist, noticed these accidental discoveries in the mid-1800s.

In 1863, the Broad Street Buildings and their gardens were sold to a railway company. When Broad Street station was built from 1863 to 1865, thousands more burials were uncovered.

Even with these disturbances, the first proper archaeological dig didn't happen until the mid-1980s. This was before the Broadgate development. Then, a much bigger archaeological excavation took place between 2011 and 2015 for the Crossrail railway project. Part of this dig was even shown on a TV show called Time Team.

What Archaeologists Found

About 400 skeletons were dug up during the 1985–86 investigation. These were kept for study.

The 2011–2015 excavations were the largest study of London's population from the 1500s to 1700s. Archaeologists carefully studied over 3,300 burials. They learned where these people came from, what jobs they had, what they ate, what illnesses they suffered, and what medicines they took. They also found items buried with people, gravestones, tombs, and coffins.

The site even showed rare evidence of early ways people tried to stop "bodysnatchers" (people who would secretly dig up bodies). They also found mass graves of people who died during the plague in the early 1600s. The findings from these excavations have been shared with the public through websites, TV shows, and museum exhibits.

Famous People Buried Here

Many different people were buried at the New Churchyard. Some notable burials include:

- Stephen Bachiler (died 1656), an English clergyman who believed in the separation of church and state in America.

- John Biddle (1615–1662), an important English thinker who didn't believe in the Trinity.

- Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654), an English botanist, herbalist, doctor, and astrologer.

- Robert Greene (1558–1592), an English writer and playwright.

- John Lilburne (1614–1657), also known as Freeborn John, an English political leader who fought for people's rights.

- Lodowicke Muggleton (1609–1698), an English religious thinker.

- Dame Mary Rowe (died 1583), the wife of Sir Thomas Rowe, who was the Lord Mayor of London when the burial ground opened.

- William Walwyn (1600–1681), an English writer and doctor who also fought for people's rights.

Records and Information

People called "keepers" were in charge of managing the burial ground. Their job was similar to a sexton, who looks after a church and its graveyard. Since the City managed the New Churchyard, some records about it can be found in the City's old documents. These are kept at the London Metropolitan Archives.

Sadly, there isn't a list of everyone buried at the New Churchyard. This is because people were usually registered at the church in the area where they lived or died, not at the burial ground itself. As part of the 2011–2015 archaeological work, volunteers helped create an online database of many of the people who were buried at the site.

Images for kids

-

Moorgate and the Moorfields area shown on the "Copperplate" map of London of the 1550s

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |