New Zealand long-tailed bat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New Zealand long-tailed bat |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Critical (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Chalinolobus |

| Species: |

C. tuberculatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chalinolobus tuberculatus (Forster, 1844)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The New Zealand long-tailed bat (scientific name: Chalinolobus tuberculatus), also called the long-tailed wattle bat or pekapeka tou-roa in Māori, is a small mammal. It eats insects and is part of a group of bats called Chalinolobus. These bats are known for having small, fleshy bumps near their lower lips and ears.

This special bat is one of only two types of land mammals that are native only to New Zealand. The other is the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat. The long-tailed bat is related to six other "wattled bat" species found in places like Australia. Interestingly, in 2021, it even won New Zealand's Bird of the Year award, even though it's not a bird!

Contents

- Understanding the Bat Family Tree

- Where Do Long-Tailed Bats Live?

- What Does a Long-Tailed Bat Look Like?

- What Do Long-Tailed Bats Eat and How Do They Hunt?

- How Bats "See" with Sound: Echolocation

- Resting and Energy Saving: Roosting and Torpor

- Reproduction and Life Cycle of Long-Tailed Bats

- How Long-Tailed Bats Live Together

- Protecting Long-Tailed Bats: Threats and Conservation

- See also

Understanding the Bat Family Tree

The New Zealand long-tailed bat belongs to a large bat family called Vespertilionidae. Our long-tailed bat is part of a smaller group, or genus, called Chalinolobus. There are 7 known species in this group, including the Chocolate wattled bat and the Hoary wattled bat.

Bats from the Vespertilionidae family started to appear about 50 million years ago. The Chalinolobus group, including our long-tailed bat, mostly lives in Oceania (like Australia and New Zealand). Over millions of years, as the land and climate changed, these bats adapted to new environments. This helped them become the different species we see today.

Where Do Long-Tailed Bats Live?

Sadly, the long-tailed bat is now very rare in New Zealand, considered "nationally critical." You can find small groups scattered across the North and South Islands, and on smaller islands like Stewart Island and Kapiti Island.

These bats avoid cities; by 2024, they were no longer found in urban areas. A key population lives in the Eglinton Valley in Fiordland. These bats travel far, sometimes up to 20 kilometers from their home base!

What Does a Long-Tailed Bat Look Like?

The long-tailed bat is quite small, like other microbats. It usually weighs between 8 and 12 grams, about two teaspoons of sugar! Pregnant females can weigh around 16 grams.

Its body is about 5-6 centimeters long, similar to your thumb. Its wingspan is wider, about 30 centimeters, helping it fly well along forest edges. It has a long tail connected to its back legs by a special skin called a patagium, which helps tell it apart from the short-tailed bat.

Female bats often have chestnut fur with white tips. Males and younger bats are darker, almost black. Underneath, their fur is pale brown, and their wings have very little hair.

What Do Long-Tailed Bats Eat and How Do They Hunt?

Favorite Foods

Long-tailed bats are insectivores, eating only insects from land and water. Their favorite meals include flies, beetles, and moths. They are not picky, eating whatever insects are easiest to find. Moths are a big treat in warmer months, giving bats lots of energy. Bats near water often eat crane flies and midges.

Hunting for Dinner

Long-tailed bats are fast and clever hunters. They use two main ways to catch food. The first is "aerial hawking," where they catch flying insects right out of the air. They often hunt over water or along forest edges.

The second method is "gleaning." This is when a bat picks an insect directly off a surface, like a leaf. This helps them catch slower-moving insects.

These bats are nocturnal, active at night. They usually start hunting about 15 to 30 minutes after sunset. If it gets too cold, below -1.5°C, they become less active and might enter torpor to save energy.

How Bats "See" with Sound: Echolocation

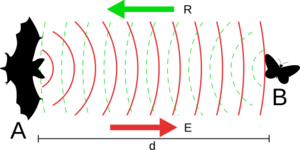

Just like many other bats, the long-tailed bat uses echolocation to find its way around and hunt for food. It sends out very quick bursts of high-pitched sounds. Then, it listens for the echoes that bounce back when these sounds hit objects. This helps the bat create a "sound map" of its surroundings.

The sounds made by the long-tailed bat are very high, around 28 kilohertz. Each sound burst lasts for about 6.3 milliseconds. These types of calls are perfect for bats that hunt along the edges of forests. Echolocation is super important for bats that catch insects in the air. It helps them know exactly where their prey is.

Resting and Energy Saving: Roosting and Torpor

Where Bats Sleep: Roosting

When long-tailed bats are not flying, they "roost" in safe spots. Roosts protect them from predators, help save energy, and raise their young. These can be hollow trees, cracks in rocks, or under tree bark.

Some bats roost alone, others in groups. In New Zealand's North Island, about 63% roost together. In the South Island, more bats (70%) prefer to roost alone.

Bats choose native trees like the NZ cabbage tree (Cordyline australis), kānuka (Kunzea ericoides), and tōtara (Podocarpus totara). They often pick dead trees in open forests.

Long-tailed bats move roosts almost every night. If in a group, they all move together to avoid predators. Female bats with babies usually stay in group roosts. They have different roosts for day and night.

Saving Energy: Torpor

Because their food supply changes with the seasons, long-tailed bats have a special way to save energy called torpor. When it's cold or wet, and there aren't many insects to eat, bats can become inactive. During torpor, their body temperature drops, and only their most important body functions keep going. This uses much less energy and helps them survive tough times.

Torpor is a bit like hibernation, but it's shorter. Instead of sleeping for months, bats enter torpor for a few hours or up to a whole day. They use this trick in all seasons, but especially in winter.

Reproduction and Life Cycle of Long-Tailed Bats

Female long-tailed bats can start having babies when they are about 2 years old. They usually have one baby, called a pup, each year until they are about 9 years old. Mating happens in late summer, but the female bats don't become pregnant until late spring.

A mother bat is pregnant for about 6 to 8 weeks. In December, a tiny pup is born. It's only about 1 centimeter long, has no hair, and cannot see. The mother bat feeds her pup milk every 1 to 3 hours. After about 4 to 5 weeks, when the pup weighs at least 7 grams, it starts to fly. Long-tailed bats usually live for about 7 to 11 years, but some might live much longer, even up to 30 years, if conditions are just right!

How Long-Tailed Bats Live Together

Large groups of long-tailed bats can have between 100 and 350 individuals. In group roosts, female bats with babies are usually the most common (about 63% of adults). Other adult females are next, followed by males.

Most long-tailed bats stay with the same group when they roost. Only a few change groups. These are usually adult males or females without babies. This suggests that female bats with young often lead their roosting groups for a long time. Scientists worry that this might reduce the variety of genes in the bat population over time.

Protecting Long-Tailed Bats: Threats and Conservation

The long-tailed bat is legally protected in New Zealand since 1953. The New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) says this bat is "Nationally Critical," meaning it's in extreme danger. DOC estimates there are between 20,000 and 100,000 long-tailed bats left.

The biggest dangers are animals that hunt them, like stoats, rats, and feral cats. These native bats didn't evolve with such predators, making them very vulnerable. When there are many stoats and rats, bat numbers drop sharply. Experts predict the population could shrink by another 90% in the next 30 years without strong action.

DOC is working hard to protect these bats. They count and tag bats to learn more. Controlling predators is a top priority where bats live. In Eglinton Valley, Fiordland, predator control has helped the bat population grow. Scientists use special bat recorders to track where bats are and how their movements change.

See also

In Spanish: Chalinolobus tuberculatus para niños

In Spanish: Chalinolobus tuberculatus para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |