Oligosoma salmo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Oligosoma salmo |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Critical (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Oligosoma |

| Species: |

O. salmo

|

| Binomial name | |

| Oligosoma salmo Melzer, Hitchmough, Bell, Chapple, & Patterson, 2019

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Oligosoma aff. infrapunctatum "Chesterfield" |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Chesterfield or Kapitia skink (Oligosoma salmo) is a special type of skink found only in New Zealand. It was first discovered in 1994. For a long time, scientists didn't realize it was a unique species.

This skink lives only in a tiny 1-kilometer strip of plants along the coast. This area is on the West Coast of New Zealand, about 15 km north of Hokitika. Sadly, there are fewer than 200 of these skinks left in the wild.

The Kapitia skink is the only New Zealand skink with a prehensile tail. This means it can use its tail to grab onto things, like a monkey uses its tail. This suggests that long ago, these skinks lived in trees in coastal forests. However, these forests were later cut down for dairy farms.

In 2018, a big cyclone damaged much of their remaining home. Because of this, a small group of skinks was taken to Auckland Zoo. There, they started a special program to help them breed and grow their numbers.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Before it got its official scientific name, this skink was called the Chesterfield skink. This name came from the only place it was known to live, Chesterfield.

Local Māori know this area as Kapitia. So, in November 2020, the skinks were also given the te reo Māori name "Kapitia skink."

The scientific name for the species is salmo. This Latin word refers to the cool salmon-pink scales found on the underside of its tail. It's a very unique color!

How This Skink Was Found

The first Kapitia skink was found in February 1992. Staff from the Department of Conservation (DOC) found it on a deer farm near Chesterfield. This farm was about 15 km north of Hokitika on the West Coast.

At first, people thought this single skink was a common cryptic skink. But then, a second skink was found in February 1993. Its tail had such unique colors that it made people want to search for more.

In March 1994, DOC officers Geoff Patterson and Shane Hall found seven small skinks. They measured five of them, which were about 53.4 mm long from snout to vent. They also collected two skinks for closer study. All of them had special pink and red tail markings. These markings made them different from common grass skinks.

In 1995, the land where these skinks lived was put up for sale. It was going to be turned into dairy pastures. A DOC team spent three days searching the area. They found four more skinks hiding under logs near streams and in the grass by the beach. After the land was sold, the skinks' habitat was destroyed. No Kapitia skinks were seen there after 2001.

Uncovering a New Species

When the Kapitia skinks were first found, scientists thought they might be related to the speckled skink. However, early studies gave mixed results. It was hard to tell if they were a truly different species.

Later, scientists used more advanced DNA studies. In 2008, these studies showed that the Chesterfield skink was indeed a distinct group. It was most closely related to another skink found near Reefton.

These DNA studies proved that the Kapitia skink was not just a variation of another species. It had split off from other skinks a very long time ago, even before the last ice age.

Finally, in 2019, scientists officially described and named the Chesterfield skinks. They were given the scientific name Oligosoma salmo.

Where Kapitia Skinks Live

The Chesterfield area is mostly dairy farms today. To the west is the Tasman Sea, and to the east is State Highway 6. Kapitia skinks now live in a very small strip of coastal plants. This area is only about 1 km long and just 5 meters wide.

Since they were discovered, much of their original home has become dairy farms. Now, they live in areas with non-native plants between farms and sand dunes. They hide under things like old metal sheets, driftwood, shrubs, and rough grass.

The Amazing Prehensile Tail

Unlike all other New Zealand skinks, the Kapitia skink has a prehensile tail. This means it can use its tail to grip objects and help it climb. Researchers noticed that when they picked up a Kapitia skink, it would wrap its tail tightly around their fingers. Other skinks can't do this.

The tail has a very strong grip. The muscles in its tail can contract so much that they form ridges. It can even hang by its tail alone! This special tail suggests that O. salmo used to climb trees. Its current habitat is likely what was left after the coastal forests were cleared for farming.

What Kapitia Skinks Look Like

The Kapitia skink is similar to the speckled skink, but it's more slender. It also has a shinier look and special patterns under its tail.

These skinks can grow up to 85 mm long from their snout to their vent (the opening at the end of their body). However, they are usually between 65–75 mm long. Their tail is longer than their body. They weigh up to 10.5 grams.

Their back is brown with light and dark speckles. They don't have a stripe down the middle of their back. Their underside is yellow and plain, with a pinkish color around their throat. They have a shiny, golden glow.

The underside of their tail starts yellow. Then, it suddenly changes to a mix of grey, black, and a unique pinkish-orange color. Each skink also has a broad reddish-brown stripe down its sides. This stripe has black edges and pale flecks. The pattern of these flecks is unique for each skink. This helps scientists identify individual skinks they catch.

Life Cycle and Habits

Kapitia skinks grow up slowly. They become old enough to have babies at about 4 years old. They give birth in late summer, usually around February. Like almost all of New Zealand's native skinks, they have live young instead of laying eggs.

One skink taken to Auckland Zoo in 2018 later gave birth to five babies. These skinks mainly hunt small creatures without backbones, like insects. Before the coastal forest was cleared, they might have also eaten berries. They are diurnal, meaning they are active during the day. They like to bask in the sun but will quickly hide if they feel disturbed.

Protecting the Kapitia Skink

By 2008, when Kapitia skinks were recognized as a separate species, none had been seen for seven years. Surveys in 2009 and 2013 found very few skinks. In 2015, surveys using traps found only 17 skinks. Another survey in November 2015 caught 52 skinks. Scientists then estimated the total population was only about 40–50 individuals.

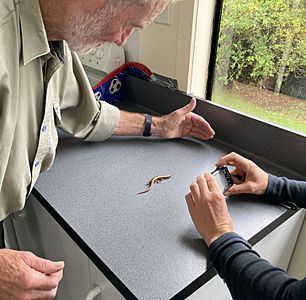

Since 2015, the Department of Conservation (DOC) has done yearly surveys. They continue to catch, photograph, measure, and identify individual skinks.

- DOC skink processing, April 2021 survey

In New Zealand, all native reptiles are protected by law. It is illegal to keep or even pick up lizards without a special permit. Handling lizards can stress them out and make them drop their tail. Their tail stores important fat.

With only about 200 individuals left in the wild, the Kapitia skink is in serious danger. The NZ TCS has listed its threat status as "Threatened–Nationally Critical" since 2009. This means it is very close to disappearing forever.

Threats to Survival

The biggest threat to these skinks right now is mice. Mice will attack lizards that are too cold to move and eat them alive. Other animals that hunt skinks include cats, hedgehogs, rats, mustelids (like stoats), and weka (a type of bird).

Their habitat is also in danger from vehicles, fires, and storms.

Rescue and Recovery Efforts

In February 2018, huge waves caused by Cyclone Fehi flooded the skinks' entire home. It destroyed almost half of their habitat. At the time, DOC researchers worried the cyclone might have wiped out the whole species.

Fearing another cyclone, DOC rangers quickly collected 50 skinks. With only 24 hours' notice, they moved them to a special breeding program. This program is at Auckland Zoo's New Zealand Centre for Conservation Medicine. This kind of rescue had worked before with cobble skinks. By November 2020, sixteen Kapitia skinks had been born safely at the zoo.

In 2019, the wild population was estimated to be around 150–200 skinks. In 2020, the DOC team found 94 skinks they hadn't seen before. This was a good sign that the population was growing after the cyclone.

In November 2020, DOC bought 1.3 hectares of coastal land where the skinks live. They plan to build a special fence to keep predators out. They also want to plant suitable trees. Eventually, they hope to release the skinks from Auckland Zoo back into this safe wild area.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |