Pikillaqta facts for kids

View of a Pikillaqta sector

|

|

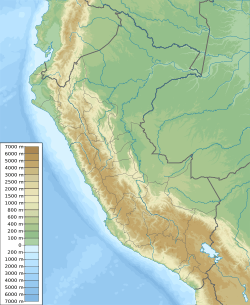

| Location | Quispicanchi Province, Cusco Region, Peru |

|---|---|

| Region | Andes |

| Coordinates | 13°37′00″S 71°42′53″W / 13.61667°S 71.71472°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 34.208 km2 (13.208 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Founded | 500 |

| Abandoned | 1200 |

| Periods | Middle Horizon |

| Cultures | Wari culture |

Pikillaqta is a big Wari culture archaeological site located about 20 kilometers (12 miles) east of Cusco in Peru. Its name comes from the Quechua language, meaning "flea place."

Pikillaqta was a town built by the Wari people. The Wari empire had its main city called Wari, and other places like Pikillaqta were important centers influenced by it. The Wari people lived in many sites across the area. This site was used from around 550 AD to 1100 AD. It was mainly used for special ceremonies and was not fully finished when the Wari left it.

Contents

Exploring Pikillaqta's Location

Pikillaqta is found 3,200 meters (about 10,500 feet) above sea level. It sits in the Lucre Basin, which is part of the eastern Valley of Cusco. This area has grassy hills mixed with rocks and sand.

The weather here is cold and dry. During winter and spring, it rains about 300 millimeters (12 inches) each month. In late spring, summer, and fall, it rains less, about 106 millimeters (4 inches). Temperatures can reach 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15°C) in warmer months. However, it often freezes in colder seasons.

Discovering Pikillaqta's Past

People have been studying Pikillaqta for almost a century. The first person to study it was Luis Valcarcel in 1927. He found two small green stone statues. Emilio Harth-Terre later drew maps of the site in 1959.

In the 1960s, William Sanders looked at the buildings from the surface. He divided the site into smaller parts. Mary Glowacki studied the pottery found there in 1996.

Most of what we know about Pikillaqta today comes from Gordon McEwan. He dug at the site three times: in 1978-79, 1981-82, and 1989-90. During his last excavation, he studied the buildings and trash piles in great detail. McEwan split the site into four sections to make his research easier.

More recently, the Peruvian Ministry of Culture did archaeological work at Pikillaqta between 2017 and 2018. They dug test pits and trenches. They also excavated around the main plaza of Pikillaqta.

Farming and Water Systems

Archaeologists found corn and 20 well-preserved beans during McEwan's digs. Corn was a very important crop for the people of Pikillaqta. They grew it using large irrigation systems. Corn was so important to the Wari culture that they painted it on their pottery. They also showed it with their gods.

Pikillaqta had canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts. These were used to water terraced fields where crops grew. The Wari people controlled the economy of the area through their farming. They had a complex water system that moved water through canals to their fields.

Water for irrigation mostly came from rainfall. During August to December, there was little rain, so they used their artificial irrigation system a lot. From December to January, there was plenty of rain, so they used less artificial irrigation. May to June was harvest season, and irrigation was used as needed.

The canals were built from stone. They connected to the Lucre River and Chelke stream. The system had over 48,000 meters (about 30 miles) of canals. Canal A and Canal B were the longest and connected directly to Pikillaqta. Canal A brought water to the most important buildings in the center of Pikillaqta. These amazing water systems helped grow crops and provided water for the people.

Archaeologists also found over 5,000 bones in the trash piles at Pikillaqta. Most of these bones were from llamas, alpacas, guinea pigs, and other small animals. These animals were likely a main source of food, along with corn. They also found spear points, which were probably used to hunt and prepare these animals.

What Was Pikillaqta Used For?

Around 650 AD, the Wari built Pikillaqta. It was a huge, strong complex covering 25 hectares (about 62 acres). It was like a fort, with soldiers guarding it. All five entrances to the valley from the high plains were heavily protected.

Pikillaqta might have been a big place for feasts. There was a large patio or plaza in the middle of the complex. This area was probably where important ceremonies and religious events took place. Leaders and their families would gather there to feast and drink. The plaza was big enough to hold ceremonies for people from other Wari towns.

People drank a lot of chicha, which is an alcoholic drink made from fermented corn. Corn and chicha were very important in their rituals. They were considered sacred and often appeared in ceremonies.

Besides the main plaza, other parts of Pikillaqta were also used for ceremonies. There were 18 "niched halls," which were important religious buildings. These halls were looted, but they might have once held sacred objects and offerings. Wari art shows ceremonies with a special pole coming out of the center of these halls. Offerings, plants, and wild cats were also shown in a sacred way. This suggests the halls were used for religious rituals.

There were also 501 small connected buildings at the site. These rooms could have been used for smaller, more private feasts and rituals. One section of these buildings might have been a place where mummies were kept and visited. Small fireplaces were found there, where offerings to the dead might have been made. The Wari believed it was important to stay connected with mummies. They thought mummies could watch over the living, so they visited them often. One of these rooms had a large stone that the Wari couldn't move. They built their structure around it, and the rock was likely used as a sacred object.

Leaders and Beliefs

While there was no clear proof of social classes at Pikillaqta, there were likely different levels of people. People with higher power would have been needed to manage the large events and ceremonies. Evidence from other Wari sites suggests that leaders would have kept everything organized.

Family connections were very important to the Wari. Many decisions and ceremonies involved "fictive kinship" (like adopted family) and worshipping ancestors. The main Wari god was Waricocha. Waricocha was known as the "staff god" who controlled life and death. He was believed to be the creator of everything: the universe, the sun, the moon, and civilization. In pottery and art, Waricocha was shown holding a staff in each hand. Rays came out of his head, showing his divine power. At the end of these rays, animals like pumas and condors were attached, along with corn.

Trade and Special Skills

Items like turquoise, a bluish-green stone, were traded into the area. This stone was used for small statues and was not found naturally in the Pikillaqta region. Other stones, gems, and minerals were also exchanged. Some experts believe Pikillaqta might have been a major center for a large trade network.

Pottery was also traded into Pikillaqta. Two main styles, Okros and Wamanga, were made in the surrounding areas. Since Pikillaqta was one of the biggest Wari sites, many other goods were probably traded in and out. These goods were likely stored in the many buildings at Pikillaqta. Many people came for the ceremonies, so they probably brought or traded many items.

Special skills were also present at Pikillaqta. The bluish-green statues found there show this. Two groups of 40 turquoise statues were found in burial sites. This number was important because it showed how organized the Wari state was. These were also the only statues found from the Middle Horizon period so far. The statues ranged in size from 18 to 52 millimeters (about 0.7 to 2 inches). There were places at Pikillaqta where turquoise was processed and workshops for carving stone. The architecture of the buildings also required great skill and time to build. Another special skill was working with bronze arsenic, as many bronze artifacts were found at the site.

Skeletal Remains Found

Archaeologists found a few burials during their digs at Pikillaqta. They uncovered two wall tombs, some offering pits, and one room with human bones. In one of the niched halls, ten skulls were found in an offering pit. Seven were buried in red soil, and three were in gray soil. A bronze metal spike was the only other item found in this pit. In another pit, bone fragments with green stains were found, suggesting they were buried with copper, though the copper itself was gone. A few shell artifacts were also found.

Many valuable items are missing from tombs and graves at Pikillaqta because of looting. The buildings show signs of being looted. Looters took valuable items that might have been buried with the skeletons.

In Wall Tomb 1, a man and a woman were found. Small turquoise-colored stone beads were with their bodies. The bodies were placed in the wall in a seated position when the building was constructed. In the second wall tomb, the body was also seated upright but had fallen over.

In total, four almost complete skeletons and ten other skulls were found at the site.

- Wall Tomb 1 had an adult male and female. The male was 35–45 years old. He had a healed broken bone from a hit to the face, a shaped skull, and gum disease. The female was 35–50 years old. She had a flattened forehead and more cavities and tooth wear than the male.

- Wall Tomb 2 had a female aged 17–20. Her bones were still growing, showing she was young.

- A partial skeleton from Unit 49 was 16–18 years old, and its bones were still forming.

- Of the 10 skulls, McEwan looked at 3. One had a shaped skull, and another had three healed holes drilled into it (a type of ancient surgery called trephination).

There was no clear evidence to show how these people died. More research is needed to learn more about them.

Why Was Pikillaqta Left?

Pikillaqta was used from about 550 AD to 1100 AD. It was completely abandoned around 1100 AD. The exact reason is not known. It might have been due to a crisis in the Wari empire. Or perhaps the Wari were trying to expand elsewhere and planned to return later.

The abandonment happened in two stages. First, the Wari people left. Then, a huge fire occurred. The site was abandoned before many of the buildings were finished. Sector 2 of the site was completed and used. After that, work continued on sectors 1, 4, and then 3.

In Sector 1, digs showed that the inside walls were not plastered with clay or white gypsum. In one area (Unit 47), there was evidence of an offering, meaning it was being built but not finished. Sector 4 had most of its buildings finished, but some walls were incomplete, and floors were unfinished. In Sector 3, one building (Unit 34) was barely started. It was full of plain soil, the walls were unfinished, and the floor was not laid. Offerings were not placed in the corners. The door was blocked with clay, probably because it was abandoned during construction. So, abandonment happened while sectors 1, 3, and 4 were still being built.

Many key doorways were sealed off to prevent unwanted visitors from entering. Some buildings were completely sealed with clay. Valuable goods were not found at the site. This might explain why very few artifacts were found anywhere.

The last part of the abandonment was a massive fire. The Wari had sealed and tried to protect the site, as if they planned to come back. McEwan believes that after they left, local people wanted to destroy the site and set it on fire. Burned beams and burning on the underside of floors suggest the fire was set on purpose. Sectors 1 and 2 were destroyed by fire. McEwan thought the Wari were trying to expand their control. Eventually, the Wari empire split apart, leading to its end.

After the fire, looters came through the site at unknown times. They got into some of the burials. They are the only known people to have been active at the site before archaeologists investigated. Today, Pikillaqta is open for visitors to see the ruins of this large complex.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Piquillacta para niños

In Spanish: Piquillacta para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |