Planarian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Planarian |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dugesia subtentaculata, a type of planarian. | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Rhabditophora |

| Clade: | Adiaphanida |

| Order: | Tricladida Lang, 1884 |

| Subdivis | |

|

|

Planarians are amazing free-living flatworms. There are hundreds of different kinds, and you can find them in freshwater, in the ocean, and even on land! They are special because they have a unique three-branched gut. This means their digestive system has one part going forward and two parts going backward.

What makes planarians super cool is their body is full of special adult stem cells called neoblasts. These cells help planarians regrow any body part they lose. Imagine if you could regrow a lost finger! Planarians can do something similar, which is why scientists study them a lot to learn about regeneration and stem cells. We even have maps of their genes and special tools to study them closely.

Planarians move by using tiny hairs called cilia on their underside. These cilia help them glide along on a layer of mucus. Some can also wiggle their whole body using muscles to move around. These little worms are important in water environments and can even tell us if the water is healthy.

Contents

Types of Planarians

Scientists group planarians into three main types based on their family tree: Maricola, Cavernicola, and Continenticola. In the past, they were grouped by where they lived: marine (ocean), freshwater, or land.

Here are the main groups of planarians:

- Order Tricladida

- Suborder Maricola (mostly marine planarians)

- Superfamily Cercyroidea

- Superfamily Bdellouroidea

- Superfamily Procerodoidea

- Suborder Cavernicola (cave-dwelling planarians)

- Family Dimarcusidae

- Suborder Continenticola (freshwater and land planarians)

- Superfamily Planarioidea

- Family Planariidae

- Family Dendrocoelidae

- Family Kenkiidae

- Superfamily Geoplanoidea

- Family Dugesiidae

- Family Geoplanidae

- Superfamily Planarioidea

- Suborder Maricola (mostly marine planarians)

Body and How It Works

Planarians are flatworms with a simple body plan. They don't have a fluid-filled body cavity like humans. The space between their organs is filled with a special tissue. They also don't have a blood system like us. Instead, they get oxygen through their skin.

They eat using a muscular tube called a pharynx, which they can stick out from their belly. Food goes into their three-branched gut. This gut is like a blind sac, meaning it has only one opening. So, planarians eat and get rid of waste through the same opening, which is in the middle of their underside.

Their body also has a system to get rid of extra liquids. It's made of many tiny tubes with special cells called flame cells. These cells push out unwanted liquids through tiny pores on the planarian's back.

The front end, or head, of a planarian usually has sense organs like eyes and chemical sensors. Some species have ear-like parts called auricles that stick out from their head. These auricles help them feel touch and detect chemicals in the water.

The number of eyes can be different for each species. Many planarians have two eyes, like Dugesia. Others have many eyes spread along their body. Planarians that live underground or in caves often have no eyes at all.

The outside of a planarian's body is covered in tiny hairs (cilia) and special rod-like structures called rhabdites. Inside, between the outer skin and the gut lining, there's a tissue called mesenchyme.

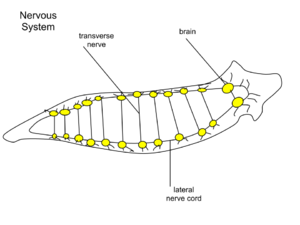

Nervous System

Planarians have a simple brain that looks like two connected lobes. From this brain, two long nerves run down to their tail. Smaller nerves connect these main nerves, making their nervous system look like a ladder. Their brain even shows electrical activity, a bit like the brain waves in other animals.

A planarian's body is soft, flat, and often wedge-shaped. It can be black, brown, blue, gray, or white. The head is usually blunt and triangular, with two eyespots that can sense light. The auricles near the head are sensitive to touch and chemicals. The mouth is on the underside, covered with cilia. They don't have a circulatory or breathing system; oxygen goes in and carbon dioxide goes out directly through their body wall.

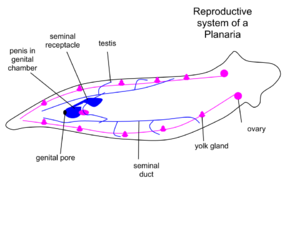

Reproduction

Planarians can reproduce in two ways: sexually and asexually. Some species can do both. Planarians are hermaphrodites, meaning each worm has both male and female reproductive parts. When they reproduce sexually, they usually exchange sperm with another planarian.

Neoblasts: Super Stem Cells

Neoblasts are amazing adult stem cells found all over a planarian's body. They are tiny, round cells with a large center part (nucleus) and a small amount of surrounding material. These cells are super important for regrowing lost body parts and organs. They also constantly make new cells to replace old ones in the planarian's body.

Unlike some other stem cells, neoblasts can create all the different types of cells a planarian needs. They divide often and directly make new cells, which is why planarians are so good at regenerating.

Planarians in Science

Planarians are like tiny superheroes for scientists! Their unique life story makes them perfect for studying many biological processes, which can even help us understand human health. Thanks to new tools, scientists can now study how genes work in these animals. Planarians are simpler than many other animals, which makes them easier to study in experiments.

Planarians have many cell types, tissues, and simple organs that are similar to those in humans. But their ability to regenerate is what really gets attention. Early scientists like Thomas Hunt Morgan studied this amazing ability, and his work still helps modern research.

Planarians are also becoming important for studying aging. Asexual planarians seem to have an endless ability to regenerate and can keep their cell parts (telomeres) from getting shorter, which is linked to aging.

Scientists also use live planarians to test how chemicals affect living things. Because they can regrow parts and react quickly to harmful substances, they are good for checking environmental and medicine dangers. For example, scientists can use a special dye to see how chemicals irritate a planarian's skin.

Regeneration: The Superpower

Planarian regeneration is incredible! When a planarian is injured, it not only grows new tissue but also reshapes its existing body to become whole again. In lab species, new working tissues can grow back in just 7 to 10 days after an injury.

When a planarian needs to regrow a part, the neoblasts near the injury start multiplying. They form a structure of new cells called a blastema. These neoblasts are the key to making new cells, providing the building blocks for regeneration. Special signals in the body tell the neoblasts what kind of cells and tissues to make. Muscle cells, for example, play a big role in sending these signals. So, both neoblasts and muscle cells are vital for successful regeneration.

People used to say planarians were "immortal under the edge of a knife." Even a tiny piece, as small as 1/279th of the original worm, can grow back into a complete planarian in a few weeks! This is all thanks to the pluripotent stem cells (neoblasts) that can create all the different cell types. These neoblasts make up 20% or more of the adult worm's cells. They are the only cells that divide, and they replace older cells. Plus, the existing body reshapes itself to make the new planarian perfectly symmetrical.

You don't even have to cut a planarian into separate pieces to see this. If you cut a planarian's head in half down the middle, and leave both halves attached, the planarian can grow two heads! Scientists have even sent planarians to space to see how microgravity affects their growth. One worm that went to the International Space Station (ISS) grew two heads after being cut, though this can also happen on Earth under certain conditions. For example, exposing cut pieces to electrical fields can make them grow two heads or even two tails! Scientists can also use chemicals or gene changes to make planarians grow extra heads or tails.

Memory Experiments

In the 1950s, scientists Robert Thompson and James V. McConnell did some interesting experiments with planarians. They taught planarians to react to a bright light as if they had received an electric shock. They did this by showing a bright light and then giving a shock. After a while, the planarians would react to the light alone.

McConnell then tried something wild: he cut the trained worms in half. Both halves regenerated, and guess what? Both new worms still showed the light-shock reaction! Later, he even ground up trained worms and fed them to untrained worms. He claimed the worms that ate the trained worms learned the trick much faster.

This experiment was meant to see if memory could be passed on chemically. However, when other scientists tried to repeat this with other animals like mice or fish, it didn't work. It's now thought that McConnell's results might have been due to him expecting to see the results (observer bias). No one else has been able to reliably show planarians reacting to light in the same way after eating trained worms.

However, in 2012, other scientists, Tal Shomrat and Michael Levin, showed that planarians can remember things even after growing a new head! This suggests they do have some form of long-term memory.

Planarians for Learning

Several planarian species are often used for science research and in schools. Schmidtea mediterranea, Schmidtea polychroa, and Dugesia japonica are popular because they regenerate well and are easy to keep in the lab. S. mediterranea is especially favored for modern gene studies because of its chromosomes and the availability of both asexual and sexual types.

In high school and college labs, you'll often see the brownish Girardia tigrina. Other common species include the blackish Planaria maculata and Girardia dorotocephala.

Images for kids

See also

- Worm Runner's Digest

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |