Port Sunlight War Memorial facts for kids

The Port Sunlight War Memorial is a special monument in the middle of Port Sunlight, a unique village in Wirral, England. The village was created by William Lever, who owned a soap factory there. He wanted a memorial to remember all his workers who bravely fought and died in World War I.

Lever asked a famous sculptor named Goscombe John to design the memorial way back in 1916. It was finished and officially revealed in 1921 by two of his own employees. The memorial is made of strong granite and features a special cross with bronze statues and detailed carvings called reliefs. Its main idea is "Defence of the Realm," meaning protecting the country. On the memorial, you can find the names of all the company's employees who died in both World War I and World War II. It's considered a very important historical site, listed as a Grade I listed building.

Building the Memorial: A Look Back

Port Sunlight was built by William Lever (1851–1925), who later became Viscount Leverhulme. He created the village for the people who worked in his soap factory. During World War I, Lever was very keen to have a war memorial in Port Sunlight. He worried that all the best sculptors would be busy after the war. So, he hired Goscombe John to design the memorial as early as 1916.

Lever was also concerned that England might be invaded during the war. Even though he was 63, he joined a local defense group. Because of this, the memorial's theme became "Defence of the Realm." This was unusual for war memorials. Since an invasion would threaten everyone at home, Lever wanted the memorial to show that everyone, including women and children, played a part in protecting the country.

Goscombe John showed his ideas for the memorial's figures at art shows in 1919 and 1920. Lever and his local committee chose the final designs. These were then cast (made) in bronze at a special foundry. The memorial itself was built by a company from Manchester.

Over 4,000 of Lever's employees served in World War I. Sadly, 503 of them died. At first, they planned to put the names of everyone who served on the memorial. But this was too difficult because there were so many names. So, only the names of those who died were included.

The memorial was officially revealed on December 3, 1921. Instead of a famous person, two employees who had served in the war were chosen for the ceremony. These were Sergeant Eames, who had lost his sight in the Battle of the Somme, and Private Robert Cruickshank, who had won the Victoria Cross for his bravery.

What the Memorial Looks Like

The memorial stands in the most important spot in the village. It's where the two widest roads meet. It's made of granite, with bronze sculptures and carvings. In the middle is a tall, special cross. This cross stands on an eight-sided base, called a plinth. On this base, there are eleven bronze statues. There are also messages carved into the sides of the plinth.

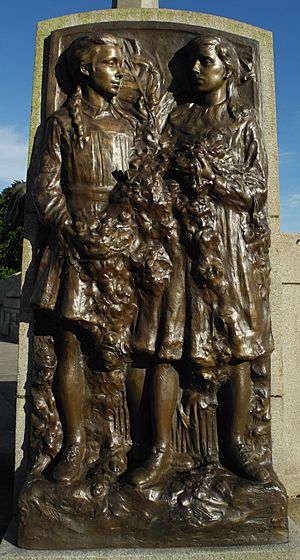

Around the plinth, there's a circular area with four places to sit. This area is surrounded by a low wall called a parapet. The wall has four sets of steps leading up to the memorial. Next to the steps are carvings of groups of children holding wreaths. Each of these carvings is different. On the four sections of the wall facing the road, there are carvings showing different parts of the armed forces. Between the steps, there are flower beds.

The whole monument is about 11.6 meters (38 feet) tall. It has a total width of about 22.4 meters (73 feet). The carvings of children are about 161 centimeters (5 feet 3 inches) tall. The carvings showing the services are about 128 centimeters (4 feet 2 inches) tall.

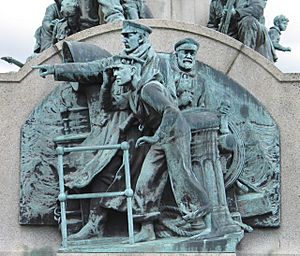

The figures on the plinth show three soldiers. One of them is hurt and is being helped by a nurse. There's also a seated woman holding a group of babies, a girl with her brother, and a Boy Scout. These statues are all bigger than real life. The carvings on the wall show the Navy, the Army, Anti-Aircraft defense, and the Red Cross.

On the front of the plinth, there are two messages. The top one says:

- THE MEMORIAL

- ERECTED BY LEVER BROTHERS LIMITED

- AND THE COMPANY'S EMPLOYEES IN ALL

- PARTS OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE AND IN

- ALLIED COUNTRIES WAS UNVEILED ON

- DECEMBER 3RD 1921 BY

- SERGEANT E.G. EAMES OF PORT SUNLIGHT

- WHO LOST HIS SIGHT AT THE FIRST BATTLE

- OF THE SOMME IN FRANCE 1916 AND BY

- PRIVATE R.E. CRUISHANK OF THE LONDON

- BRANCH OFFICE WHO WAS AWARDED THE

- VICTORIA CROSS IN 1918 FOR CONSPICUOUS

- BRAVERY AND DEVOTION TO DUTY IN PALESTINE.

And the bottom message says:

- THE NAMES OF ALL THOSE WHO SERVED NUMBERING OVER FOUR

- THOUSAND ARE RECORDED IN A BOOK DEPOSITED BENEATH

- THIS STONE AND ALSO IN SIMILAR BOOKS PLACED IN

- CHRIST CHURCH AND IN THE LADY LEVER ART GALLERY.

On the back of the plinth, the top message says:

- THESE ARE NOT DEAD

- SUCH SPIRITS NEVER DIE.

- ON THE ADJOINING PANELS ARE INSCRIBED

- THE NAMES OF THOSE

- FROM THE OFFICES AND WORKS OF

- LEVER BROTHERS LIMITED

- AND THEIR ASSOCIATED COMPANIES OVERSEAS

- AND ALSO FROM PORT SUNLIGHT

- WHO LAID DOWN THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR

- 1914-1919.

Below this, the dates 1939–1945 are carved, remembering World War II.

Around the outside of the low wall, this message is carved:

- DULCE ET DECORUM

- EST PRO PATRIA MORI

- THEIR NAME

- SHALL REMAIN

- FOR EVER AND

- THEIR GLORY

- SHALL NOT BE

- BLOTTED OUT.

On the back of each of the four seats, it says "TO OUR GLORIOUS DEAD."

On all the other sides of the plinth, you can find the names of those who died in both World Wars.

Why the Memorial is Important

The Port Sunlight War Memorial was first recognized as a Grade II listed building in 1965. This means it's a building of special historical interest. In 2014, its status was raised to Grade I. This is the highest level of listing and means it's considered a building of exceptional importance.

When the models for the memorial were shown at art exhibitions, many critics were impressed by how realistic they looked. However, not everyone liked them. Some thought the figures were too lifelike for a memorial. The company's architect, James Lomax-Simpson, felt it was too complicated. He would have preferred something simpler and more symbolic. But the famous architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner thought it was "genuinely moving" and not overly sentimental. Others have also described it as "deeply moving."

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |