William Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Leverhulme

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Wirral |

|

| In office 1906–1909 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph Hoult |

| Succeeded by | Gershom Stewart |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Hesketh Lever

19 September 1851 Bolton, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 7 May 1925 (aged 73) Hampstead, London, England |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Ellen Hulme |

| Children | William, 2nd Viscount Leverhulme |

| Education | Bolton Church Institute University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Industrialist, philanthropist and politician |

| Known for | Lever Brothers |

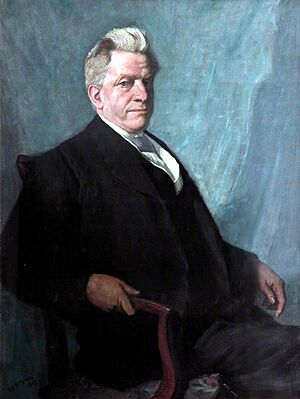

William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (born September 19, 1851 – died May 7, 1925) was an English businessman, a person who gives money to good causes, and a politician. He started working in his father's grocery business in Bolton at age fifteen.

He became famous for making Sunlight Soap. He built a huge business empire with well-known brands like Lux and Lifebuoy. In 1886, he and his brother, James, started Lever Brothers. This company was one of the first to make soap from plant oils. Today, it is part of the big British company Unilever.

In politics, Lever was a Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for Wirral. Later, as Lord Leverhulme, he served in the House of Lords. He also supported the growth of the British Empire, especially in Africa and Asia, where his company got palm oil for its products. Lever was also a big supporter of the arts. He collected many paintings and opened the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight in 1922, dedicating it to his wife, Elizabeth.

Contents

William Lever's Early Life

William Lever was born on September 19, 1851, in Bolton, England. He was the oldest son of James Lever, a grocer. William went to small private schools and then to Bolton Church Institute. He wasn't the best student, but he loved learning.

His mother wanted him to become a doctor, and William wanted to be an architect. But his father had other plans. Soon after his fifteenth birthday, William started working in the family grocery business. He had to sweep floors and tidy up before others arrived. He also learned about the wholesale grocery trade. He earned "a shilling a week all found," which meant his food and lodging were covered, and he got a small amount of pocket money.

William later moved to the office, where he helped organize the company's accounting. He then became a sales representative, which meant traveling a lot by horse and carriage. This gave him independence and a chance to make deals with shopkeepers.

The Lever family were Congregationalists, a type of Christian group. They were very strict, and William grew up with friends who shared similar beliefs. He married Elizabeth Ellen Hulme on April 17, 1874.

In 1879, the family business bought a struggling grocery store in Wigan. This gave William a chance to show his skills. He traveled to Ireland, France, and other parts of Europe to find new suppliers. He also started to show his talent for advertising and creating brands. By 1881, the business was growing steadily.

The Story of Sunlight Soap

In 1884, William Lever decided he wanted to make and sell soap around the world. Instead of selling soap by weight, he cut it into small, easy-to-use bars and wrapped them individually. This was a new idea! He also registered many brand names, including Sunlight. This helped protect his products from fakes and made customers loyal to his brand.

The first Sunlight soaps came in different colors: Pale, Mottled, and Brown. There was also a special soap for washing clothes called 'Sunlight Self-Washer Soap'. Lever advertised this soap widely with billboards and posters.

At first, Lever relied on other companies to make his soap. But sometimes, the quality wasn't consistent, and people complained. So, William decided to make the soap himself. In 1885, Lever and Company started making soap.

Sunlight soap became incredibly popular. By 1887, the factory couldn't make enough soap. So, Lever decided to move the entire manufacturing plant to a new, larger site near Birkenhead.

Building Port Sunlight Village

In 1887, Lever bought a large piece of land on the Wirral in Cheshire. This became the site for his new factory and a special village called 'Port Sunlight'. He built this model village to house his employees.

From 1888, Port Sunlight offered good homes and living conditions. Lever believed that good housing would make his workers healthy and happy. The village had everything workers needed, like shops and community places. However, there were also rules about how people lived in the village. For example, if a worker lost their job, they could also lose their home.

Lever wanted the residents to have some say in their community. But workers' social lives were sometimes watched by the company. Some employees didn't like this, even though Lever meant well. They felt it limited their freedom.

Clever Advertising Ideas

Lever's business grew quickly because of his smart advertising. Much of the Sunlight soap advertising focused on making life easier for working-class housewives. Lever got ideas from the United States for his advertising campaigns.

One idea was to tell women that hard housework made them age faster, and Sunlight Soap could help them feel more free. These messages were put on billboards and buses with pictures. The company also gave out booklets with instructions on how to use their products.

One amazing project was the Sunlight Year Book, first published in 1895. These were big books, sometimes with hundreds of pages, full of useful information for families. They were given out widely, even to school teachers.

Lever also used other ideas like competitions with cash prizes, coupons in soap packages, and sponsoring good causes, like a lifeboat named Sunlight. These ideas were so successful that other soap makers started using them too.

Lever wanted to talk directly to customers. So, he hired "District Agents" to tell people about his products. These agents also reported back anything they saw that could help the company. This strategy worked so well that Lever opened his first overseas factory in Switzerland. By 1900, Lever had factories in Switzerland, Germany, Canada, the United States, Holland, and Australia. The Sunlight brand also grew with new products like Lifebuoy, Vim, and Lux.

The "Soap Trust" Controversy

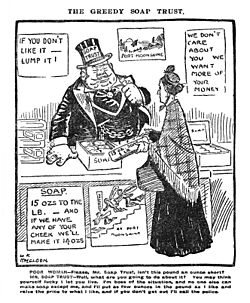

Around 1905, the cost of materials for making soap went up a lot. This made competition very tough among soap makers. In 1906, Lever and other soap makers met to try and control prices and reduce competition. This was called the "Soap Trust."

Lever said this would make the industry more efficient and save money for customers, but this wasn't true. As news of their plans leaked to newspapers, people became very angry. Newspapers like the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror published headlines like "Soap Trust Arithmetic – How 15 ounces make a pound," suggesting that the companies were cheating customers. They also claimed the Trust was trying to control raw materials and use bad ingredients.

The newspapers attacked Lever personally, calling his factory "Port Moonshine" and saying it was a bad place to work. Lord Northcliffe, who owned many newspapers, led the campaign against the Soap Trust. He believed it was wrong for companies to try and control prices.

The campaign had a huge negative impact. By November 1906, Lever Brothers' sales dropped by 60%, and their shares lost a quarter of their value. Other companies in the Trust also suffered. So, the companies decided to end the "Soap Trust." Lever estimated his losses were over half a million pounds. For Northcliffe, this was a victory for the public.

Winning a Libel Case

William Lever felt that the failure of the Soap Trust was because of personal attacks on him. He decided to sue the newspapers for libel (publishing false and damaging statements). His lawyers were confident they would win.

In July 1907, the case went to court in Liverpool. Lever's lawyer accused the newspapers of running a mean campaign to destroy Lever Brothers. He asked the jury to award a lot of money in damages.

The next day, the newspapers' lawyers gave up. They said they wanted to take back "every accusation made upon Mr Lever's honor and integrity" and were very sorry for their attacks. Lever was awarded £50,000, plus another £40,000 from individual newspapers. This was a huge victory! Lever celebrated by giving his employees a day off at Port Sunlight.

Even though Lever Brothers had been hurt by the newspapers and rising costs, Lever didn't use the money he won to help his company. Instead, he gave it all to Liverpool University. He gave large sums to departments like Town Planning, Tropical Medicine, and Russian Studies.

Lever's Work in Africa

In the early 1900s, Lever used palm oil from British colonies in West Africa. When it became hard to get more land for palm plantations there, he looked elsewhere. In 1911, Lever made a deal with the Belgian Government to get palm oil from the Belgian Congo. He started a company called Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB) and bought a huge area of forest for palm oil production. The main base was set up at Leverville.

The town of Leverville was a project where the Belgian Government and Lever Brothers wanted to create a "moral" way of doing business in Central Africa. Lever believed that paying workers and providing schools, hospitals, and food would attract people. However, the work was very hard and dangerous, and the pay was low, so not many people wanted to work there voluntarily.

Because of this, HCB worked with the Belgian colonial authorities, who had a system where people were made to work. The Belgian government was happy to partner with Lever, as he was known for his good social policies in Britain. This partnership allowed Lever to get the workers he needed. Some records show that Belgian officials, missionaries, and doctors protested against the practices at the Lever plantations.

Today, the company's former Congo plantations are run by Feronia Inc., employing about 4,000 people.

Plans for Lewis & Harris

In 1918, Lord Leverhulme bought the Isle of Lewis and later South Harris in Scotland. He had big plans to bring prosperity to these islands by creating a large and successful fishing industry. He wanted to use modern science and his business skills.

He planned to improve the harbor at Stornoway to attract fishing boats. He also wanted to build an ice-making factory and use ships with refrigerators to take fresh fish to the British mainland. Leverhulme also expanded facilities for processing fish, adding a canning factory and a plant to make fishcakes, animal feed, and fertilizer.

He also bought fish shops across the UK, modernizing them and putting their previous owners in charge. This part of his business was called Mac Fisheries, and it became very successful.

Leverhulme wanted a reliable workforce for his island plans. He hoped to hire the local Gaelic-speaking crofters, who were mainly farmers. They were poor but used to an independent way of life. Leverhulme wanted to offer them a better alternative to their small farms.

However, his plans didn't suit everyone. Some politicians and local people wanted to divide up the land into more small farms for the crofters, as allowed by a law from 1911. Leverhulme disagreed, believing his industrial plans would bring much better living standards.

In early 1919, some men started taking over Leverhulme's farms on Lewis. They drove off livestock and marked out plots of land. Leverhulme didn't want to prosecute these former soldiers who were trying to find homes. Instead, he tried to persuade them that their future was with his projects. But most preferred their traditional farming way of life.

The conflict grew, and Leverhulme faced financial problems with another company. So, he decided to focus only on Stornoway and Harris, abandoning his plans for the country areas of Lewis.

The people of Harris were fewer and more spread out, so Leverhulme's plans went more smoothly there. The fishing village of Obbe was even renamed Leverburgh. In 1923, Lord Leverhulme asked the Stornoway Council to take over the land and make their system work. Stornoway accepted and made it work for the town's benefit. Leverhulme sold off much of the land he no longer wanted. He died in May 1925, and soon after, all development on Harris stopped. His big plans for the Western Isles mostly ended with him.

William Lever's Political Life

William Lever was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party throughout his life. He ran for Parliament several times before finally winning the seat for Wirral in 1906.

In his first speech in the House of Commons, he urged the government to create a national old-age pension, similar to the one he provided for his own workers.

In 1911, he was made a baronet, a special title. Then, in 1917, he was given the title Baron Leverhulme. The "hulme" part of his title was in honor of his wife, Elizabeth Hulme.

Lever was also a justice of the peace for Cheshire and the High Sheriff of Lancashire in 1917. In 1918, he was invited to become Mayor of Bolton, even though he wasn't a council member. This showed how much the people of Bolton respected him. In 1922, he was given an even higher title: Viscount Leverhulme.

Lever's Homes

William Lever lived in and changed many houses during his life. Three of his most important homes were Thornton Manor, The Hill in London, and The Bungalow at Rivington.

Thornton Manor, Cheshire

In 1888, Lever rented and then bought Thornton Manor in Thornton Hough, Cheshire. He bought more land in the village, and many old houses were replaced with modern ones for his Port Sunlight employees. The village also got a school, shops, and a church. Thornton Manor itself was rebuilt, and its gardens were made much larger.

The Hill at Hampstead

In 1904, Lever bought The Hill, a large house in Hampstead, London. After his death, it was renamed Inverforth House. He rebuilt the house, adding new sections, a ballroom, and an art gallery. He bought two nearby properties to expand his garden, which led to a disagreement with the local council about a public pathway. The Hill became his main home from 1919.

The Bungalow at Rivington

In 1913, the suffragette Edith Rigby claimed she set fire to Leverhulme's bungalow at Rivington. The fire caused about £20,000 worth of damage to the property, which held many valuable paintings.

William Lever's Legacy

William Lever died on May 7, 1925, at his home in Hampstead. He was 73 years old. About 30,000 people attended his funeral. He is buried in the churchyard of Christ Church in Port Sunlight. His son, William Lever, 2nd Viscount Leverhulme, took over his titles.

Lever gave a lot of money to his hometown, Bolton.

- In 1899, he bought and restored Hall i' th' Wood, a historic house, turning it into a museum.

- In 1902, he donated land and created Lever Park in Rivington.

- In 1913, he helped create Bolton School.

- In 1914, he donated the land for Bolton's largest park, Leverhulme Park.

- He also gave money to buy land for the Perivale Wood Local Nature Reserve in London.

Lever also supported a school of tropical medicine at Liverpool University. He gave Lancaster House in London to the British nation. He also set up the Leverhulme Trust, which provides money for education and research. This trust continues to support schools today.

The garden of his former London home, 'The Hill' in Hampstead, is now open to the public. In 2002, a blue plaque was put on Inverforth House to remember Lever.

Lever built many houses in Thornton Hough, making it a model village like Port Sunlight. In 1906, he built Saint George's United Reformed Church there. The Lady Lever Art Gallery opened in 1922 in Port Sunlight.

Honours and Titles

- Lever Baronetcy, of Thornton Manor (1911)

- Baron Leverhulme, of Bolton-le-Moors (1917)

- Viscount Leverhulme, of The Western Isles (1922)

- High Sheriff of Lancashire, 1917

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |