Potrero Point facts for kids

Potrero Point in San Francisco was once home to some of the most important factories and businesses in the Western United States. It is located on the eastern side of Potrero Hill, a natural piece of land that reaches into San Francisco Bay near Mission Bay. To make space for industries, parts of Potrero Point were blasted away and flattened. This work created a lot of flat land for factories and provided rock to fill in other areas of the bay.

This area has been used for industry since the 1860s. It started with places to store gunpowder and small businesses that worked with ships. Later, famous companies like Pacific Rolling Mills and Union Iron Works built their factories here. Shipyards, power plants, and other related businesses also grew up in the area. These power plants eventually became part of Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E).

Potrero Point, especially around Twentieth Street and Illinois Street, still has amazing examples of an old industrial town. Many important things were made here. For example, the first locomotive (train engine), typewriter, printing press, and cable car parts were all built in Potrero. Even the famous battleship Oregon and steel for many of San Francisco's 19th-century buildings came from this busy place.

Contents

Geography of Potrero Point

Potrero Point, which used to be called Point San Quentin, was a piece of land that stuck out from Potrero Hill into the bay. Over the last 150 years, Potrero Point and the areas around it have changed a lot. Today, only a small part of the original hill remains.

After the California Gold Rush, business owners became interested in Potrero Point. It had cheap land that was away from the busy city center. It also had natural deep water, which was perfect for ships. These business owners wanted to use these natural benefits. They also needed to solve the problem of the swampy Mission Bay nearby. To do this, they filled in parts of the bay. Much of the dirt and rock for this filling came from blasting away the hills that once stood above the point. The land that extended into the bay was first cut off by Third Street and then flattened to create more building space.

The shape of the bay, with Mission Bay separating Potrero Point from much of the city, led to the building of Long Bridge in 1868. This bridge connected Potrero Point to the city and went further south. Eventually, Mission Bay was completely filled in. The shoreline south of Potrero Point was also changed a lot to make room for all the new factories and buildings.

History of Industry

Early Days

Because of its natural shape, the point was a perfect "potrero," which means a pasture or grazing land in Spanish. A Mexican landowner named Don Francisco de Haro used the land to raise sheep and cattle for many years. After the Mexican–American War, the United States took control of California. The DeHaro family then lost their claim to the land after a long legal fight.

By 1863, some development had started on Potrero Point. There were two powder magazines (places to store gunpowder) on the south side of the land. They were put there to keep dangerous materials away from people. Heavy industry first arrived in 1866. Six wealthy San Francisco business owners started the Pacific Rolling Mills. Their goal was to make iron products from scrap metal, hoping to produce iron right here in California. They needed deep water access to bring in coal from Australia, bricks from England, and scrap iron from all over the Pacific.

There wasn't much flat land at the site, so cutting down the hill and filling in the bay became very important. Eventually, two square miles of Potrero Point were removed, creating hundreds of acres of flat land for factories. Within two years, and after spending a million dollars, they had foundries (places to melt metal), piers, warehouses, and docks. The first finished iron ever made on the West Coast came out of this mill.

As San Francisco grew, so did the need for iron products. With more railroads and streetcars on the West Coast, the Pacific Rolling Mills doubled its output, and then doubled it again. By 1873, the mill made all kinds of iron products needed by the growing city. By the late 1880s, the mill had five main buildings along three blocks of waterfront and employed a thousand men. Potrero Point quickly became a key site for important industries, including shipbuilding and making mining machines. The hill continued to be cut down, and the bay mudflats were filled in. Submarines were even built near the Union Iron Works shipyards in Potrero.

World War I and II

During World War I, the Union Iron Works built many important ships, including a large number of destroyers. In August 1917, the United States Navy took over the shipyards, all ships being built, and the 9,000 workers to help with the war effort. From 1917 to 1924, the Potrero yards built many destroyers and submarines. On July 4, 1918, a special day, four destroyers were launched, and the building of four new ones began at the Union Iron Works yards.

From 1914 to 1945, the northern parts of Potrero Point were very busy with shipbuilding, repairs, and upgrades. The Union yard was always active and was the main place in San Francisco for ship repairs. Even between the wars, shipbuilding and especially refitting ships continued at the Potrero yards.

Before 1941, the shipyard at what is now Pier 70 built some of its best ships. By the late 1930s, as war seemed likely, Bethlehem Steel (which owned the yards) started to modernize the Potrero Yard. Many new buildings were constructed. By the time World War II began, Potrero was one of the most productive shipyards in the country. During World War II, the government again took over the Potrero Point yards for the war. Up to 4,000 men and women worked there, sometimes in three shifts a day. It was hard to find skilled workers during wartime, so a lot of effort went into training new people. Shipbuilding was organized so that less skilled workers could help. At the peak of the war, productivity was amazing: the destroyer escort Fieberling was built in just 24 days! Building a modern warship that fast was an incredible achievement. During the war, Bethlehem's Potrero yard built 72 vessels (52 for combat) and repaired over 2,500 Navy and commercial ships.

Bethlehem Shipyards, along with other yards in the San Francisco Bay Area, made this region the most productive shipbuilding area in the U.S. during World War II.

After the Wars

After the intense period of ship repair during the war, the Potrero Point shipyards slowly became less busy. From 1947 to 1953, no new ships were built. The yards were used mainly for repairs and upgrades. In the 1960s, a special area was set up to build parts for the underwater tube of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. Also in the 1960s, Bethlehem Steel built the largest floating drydock in the world at Potrero. In the 1980s, the city of San Francisco bought the property for one dollar. The Todd Shipyard Corporation then bought the plant and equipment for $14 million and leased the site from the city. Today, work is still done there by the San Francisco Drydock Company.

Major Businesses

Today, Pier 70 in San Francisco is used by BAE Systems Ship Repair and Sims Group, a metal recycling company. The Port of San Francisco has plans to develop the area further.

Potrero Generating Station

The Potrero Generating Station was a power plant that used natural gas and oil to create electricity. It was located where California's very first electrical power plant once stood. This plant supplied about one-third of San Francisco's power needs. It was shut down in January 2011.

The Union Iron Works, located on Potrero Point, is the longest-running privately owned shipyard in the country. It built the first steel-hulled ship on the West Coast. It also built several famous warships, including the Olympia and two Plunger class submarines.

Making Gas for the City

In 1872, the City Gas Company joined Pacific Rolling Mills in Potrero. This company built a plant to turn coal into gas for lighting the city. They used steam from burning coal (and later fuel oil) to create heat, power, and electricity. For many years, the gas plant in Potrero was the biggest and most important gas factory in San Francisco. Construction started in 1870. At first, it made gas from coal. Later, it also used oil to make gas. By 1905, PG&E had taken over most of the power production in the state, including the Potrero plant. After 1906, the plant only made gas from oil. For fifty years, the Potrero plant used gas to power steam turbines and provide electricity to San Francisco.

In 1930, natural gas could be transported over long distances in California, and it arrived at Potrero. The Potrero gas works were then put on standby, meaning they were ready to be used if needed, but they were eventually taken apart in the 1950s.

California Sugar Refinery

Claus Spreckels, an immigrant from Germany, started making sugar in 1867. His California Sugar Refinery grew too big for its first location. In 1881, he moved it to the southern part of Potrero Point. This new location had deep water access for ships carrying sugarcane from the Hawaiian islands, where Spreckels owned cane farms. In the 1890s, Spreckels joined a large national sugar company. The refinery in Potrero was then renamed the Western Sugar Refinery. The huge brick buildings from the Victorian era were used until they were torn down in 1951.

California Barrel Company

Among the many businesses related to shipping in Potrero was the "California Barrel Company." This company had five large buildings, including three warehouses, a power plant, and the factory itself.

Other Businesses

Also dating back to the 1850s was the Tubbs Cordage Company. This company made rope and was located at the southern edge of Potrero Point. It was started by two brothers who realized the West needed rope for its growing shipping industries. They brought skilled workers from New England who became the core of the Tubbs workforce for decades. Tubbs imported raw materials from the Philippines and became a worldwide business. Many other shipping-related industries also had their factories at Potrero.

Workers and Unions

The history of workers in the Potrero shipyards is not fully recorded. Companies like Bethlehem Shipbuilding, just like Union Iron Works, tried hard to prevent workers from forming unions. Strikes, some of them lasting a long time, happened often during the active shipbuilding years, even during and right after the wars. One important strike in the spring of 1941 stopped major naval shipbuilding for a month and a half. This led President Roosevelt to get involved to try and end the strike. Members of the machinist union's local group resisted the government and their own national leaders, and they continued the strike. For the first time, they succeeded in getting a "closed shop" at Bethlehem, meaning all workers had to be union members.

Environmental Concerns

Starting in the 1870s, the factories in Potrero burned tons of coal, oil, and natural gas. These included gas plants, iron foundries, steel mills, shipyards, and a sugar refinery. All this burning released pollution into the air and the bay waters.

These industries, especially the gas plants that made gas for lighting and power, polluted the air, soil, and surrounding communities for decades. They left behind large amounts of harmful chemicals like hydrocarbons, sulfur, acids, carbon dust, ash, and heavy metals such as lead and mercury. The factories and their outdoor storage areas for coal and oil polluted vast areas of bay mud and water. Constant dumping and dredging of polluted materials spread the problem along the entire Potrero shoreline. About two square miles of Potrero Hill were even blasted and dumped into the bay.

The PG&E plant produced millions of cubic feet of gas each year. By 1878, it was using nearly 300,000 pounds of coal every day. The plant continued to grow and change its methods of making gas over the years. The last time it was used was in 1953, and the entire gas plant was taken apart in the late 1950s.

The gas plants were built on unpaved soil. Their waste, like coal dust and carbon, was sometimes reused as fuel, dumped into the bay, or sent south by train. It was mixed with soil and rock to fill in Islais Creek and create new land on the bay mud. It was common practice back then to give away or sell ash and cinders from furnaces for road building.

The PG&E property in Potrero does not have a continuous seawall. This means that the bay's tides can wash through the polluted ground twice a day. Underground, there are still remains of the shipyards, steel mills, sugar refinery, and gas production sites. This includes old coal tracks, tunnels, storage pits for ash and coal, foundations from fuel oil tanks, and other buried structures. Many of these were simply filled in and left underground.

These old industrial remains are mixed with thousands of wooden piles and railroad ties. These wooden pieces were treated with chemicals like arsenic, lead, and creosote to protect them from sea creatures. If they were removed, it would create direct paths for polluted groundwater to flow into the bay. Leaving them in place means that tainted groundwater will continue to flow into the bay.

Historic Station A, a large brick building from 1910, was once a modern oil-fired electrical plant. It shows how the area was constantly rebuilt as technology changed. Station A was abandoned in 1979 and still contains harmful pollutants.

In the 1970s, any material dredged from the shipyards had to be dumped far out at sea. The area's environmental problems also include pollution from the Navy's use during both world wars and illegally dumped waste in the Pier 70-72 landfill.

On top of this old pollution, more recent problems in Potrero include lead paint dust from sandblasting ships, leaking waste barrels, and underground diesel oil tanks. In 1986, the shipyard was sued by the city for mishandling electrical equipment containing PCBs and for regularly releasing raw sewage.

Currently, the city uses part of the area to store towed and abandoned cars. These cars leak fluids onto broken pavement, which then drains into the bay. A car parts dismantling business is located on dirt lots next to the power plant. There is also a toxic dump at what was called the Wilson Warehouse to the north.

Many trucking companies and a truck parking yard, covered by asphalt, are located just north of the PG&E (now Mirant) power plant. This area was once Navy shipbuilding ways that were filled in 1970 with construction waste, soil, concrete, and unapproved waste. Tests have found chemicals like hydrocarbons and benzene in the bay mud and old Navy slips. Other identified wastes include paint, oil, batteries, and unknown drums. The two main owners of the filled land in Potrero are the Port of San Francisco and PG&E, before PG&E sold to Mirant. However, the environmental responsibilities still belong to PG&E.

The Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, and Hunter's Point neighborhoods are next to the Potrero Point industrial area. The Port of San Francisco has not done enough to protect the remaining parts of this once-important industrial village. It was the most important heavy industry site in the West for a hundred years, but now it faces damage, earthquake risks, weather exposure, and official neglect. The Port says they cannot make a working shipyard a historical landmark, but the San Francisco Drydock Company has given most of the historic properties and land back to the Port.

Historic Buildings

Potrero Point is considered important enough to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This is because of its role in three wars (Spanish–American War, World War I, and World War II) and because of the 19th-century buildings that are still there. Some of these buildings are important enough to be made individual historical landmarks because of their design and history. Buildings that deserve historical landmark status include the 1917 Frederick Meyer Renaissance Revival Bethlehem office building, the 1912 Power House#1 designed by Charles P. Weeks, the 1896 Union Iron Works office designed by Percy & Hamilton, and the huge 1885 Machine shops.

- A Century of Progress 1849-1949 Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation

- Port of San Francisco Waterfront Land Use Plan - City of SF Planning Dept Final EIR January 9, 1997

Landmarks Board - San Francisco Nomination Forms

Images for kids

-

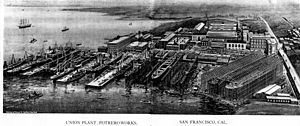

Pier area around 1918, looking north to Union Iron Works at Potrero Point

-

Claus Spreckels Sugar Factory in Potrero Point in 1892

See also

In Spanish: Punta Potrero para niños

In Spanish: Punta Potrero para niños