Grigori Rasputin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Grigori Rasputin

|

|

|---|---|

| Григорий Распутин | |

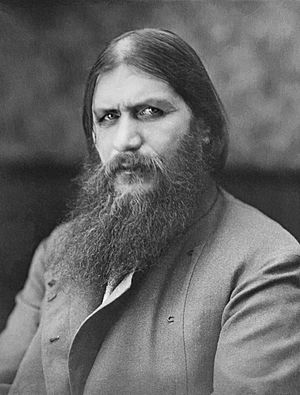

Portrait of Rasputin, around the 1910s

|

|

| Born | 21 January 1869 Pokrovskoye, Russia

|

| Died | 30 December 1916 (aged 47) Petrograd, Russia

|

| Occupation | Christian mystic |

| Spouse(s) |

Praskovya Fedorovna Dubrovina

(m. 1887) |

| Children | 3, including Maria |

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (born January 21, 1869; died December 30, 1916) was a Russian peasant who became a famous mystic and spiritual healer. He is best known for his close friendship with the family of Tsar Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia. This friendship gave him a lot of influence during the final years of the Russian Empire.

Born a peasant in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye, Rasputin had a life-changing religious experience as a young man. He became a strannik, or a holy wanderer, traveling and praying. Even though he was very religious, he never held an official role in the Russian Orthodox Church.

In 1905, he traveled to Saint Petersburg, the capital of Russia at the time. There, he met Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Soon after, Rasputin began to act as a healer for their only son, Alexei, who had a serious illness called haemophilia.

At the royal court, people had strong opinions about Rasputin. Some saw him as a true holy man and a prophet. Others thought he was a fake and were suspicious of his influence over the royal family. His power grew, especially during World War I when the Tsar was away leading the army. As Russia faced problems in the war, Rasputin and Empress Alexandra became very unpopular.

In December 1916, a group of Russian nobles who disliked his influence assassinated him. Many historians believe that the negative rumors about Rasputin damaged the reputation of the royal family and may have contributed to the end of the Russian Empire. He remains a mysterious and fascinating figure in history.

Contents

Early Life

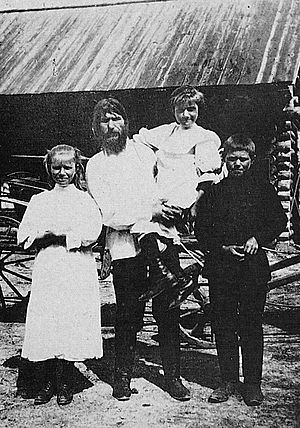

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was born in the small Siberian village of Pokrovskoye. His father, Yefim, was a peasant farmer and church elder. His mother was Anna Parshukova. Grigori had seven brothers and sisters, but they all died as babies or young children.

Like most peasants in Siberia at the time, Rasputin did not go to school. He remained illiterate, meaning he could not read or write, until he was an adult.

In 1886, he met a peasant girl named Praskovya Dubrovina. They married in 1887. Praskovya stayed in their home village of Pokrovskoye while Rasputin traveled. They had seven children together, but only three lived to become adults: Dmitry, Maria, and Varvara.

Religious Conversion

When he was 28 years old, in 1897, Rasputin became very interested in religion. He left his village to go on a pilgrimage, a long journey to a holy place. He visited the St. Nicholas Monastery in Verkhoturye. There, he met a holy elder known as a starets named Makary. This experience changed him deeply. It was possibly at this monastery that he learned to read and write.

When he returned home, Rasputin was a different man. He became a vegetarian, stopped drinking alcohol, and spent much of his time praying. For the next few years, he lived as a strannik, or holy wanderer. He would leave home for months or even years to visit holy sites across the country.

Back in Pokrovskoye, a small group of followers, mostly family and local peasants, began to pray with him. They held their meetings in a secret chapel he built in his father's cellar. Some villagers were suspicious of these secret meetings, but investigations never found that he was part of any forbidden religious groups.

Rise to Prominence

By the early 1900s, people in Siberia started hearing about Rasputin's wisdom and charisma. He traveled to the city of Kazan, where he became known as a wise man who could help people with their spiritual problems. Church leaders were impressed with him and helped him travel to Saint Petersburg.

In Saint Petersburg, Rasputin met important church leaders like Archimandrite Theofan, who was a teacher to the empress. Theofan introduced Rasputin to the city's high society. At that time, many wealthy and powerful people in Russia were interested in mysticism and the supernatural. Rasputin, with his simple peasant background and strong religious ideas, fascinated them.

Through these new connections, Rasputin met Princess Militsa and Princess Anastasia of Montenegro. They were married to cousins of the Tsar and introduced Rasputin to the royal family.

Rasputin first met Tsar Nicholas II on November 1, 1905. The Tsar wrote in his diary that he and Empress Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God – Grigory, from Tobolsk province."

Healer to Alexei Nikolaevich

Much of Rasputin's influence came from the belief that he could heal the Tsar's only son, Alexei. Alexei suffered from haemophilia, a rare condition where the blood does not clot properly. This meant that even a small bump or cut could cause dangerous bleeding that was difficult to stop.

The Empress Alexandra was desperate to find help for her son. She came to believe that Rasputin had a miraculous power to heal him.

A famous event happened in 1912. Alexei had a bad fall from a carriage ride, which caused severe internal bleeding. The doctors could not help him, and it seemed like the young boy was close to death. In desperation, Alexandra sent a telegram to Rasputin, who was in Siberia, asking him to pray for Alexei.

Rasputin sent a telegram back that said, "God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much." The next day, Alexei's bleeding stopped. The doctors called his recovery "wholly inexplicable from a medical point of view." From that moment on, Alexandra believed that Rasputin was essential for her son's survival.

Friendship with the Imperial Children

Rasputin was also a friend to the Tsar's children: the four Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia, and their brother Alexei. They were taught to view him as "our friend" and to trust him. The children seemed to like him and felt comfortable with him.

He often sent them kind and thoughtful messages. In one telegram to nine-year-old Grand Duchess Maria, he wrote, "My Dear Pearl M! Tell me how you talked with the sea, with nature! I miss your simple soul. We will see each other soon! A big kiss."

However, Rasputin's closeness to the children and the Empress caused concern among other members of the royal family and the public. These worries led to many negative rumors spreading about him, which damaged his reputation.

Failed Assassination Attempt

On July 12, 1914, a peasant woman named Khioniya Guseva attacked Rasputin with a knife outside his home in Pokrovskoye. She was a follower of a former priest who strongly disliked Rasputin.

Rasputin was very badly hurt, and for a while, it was not clear if he would survive. After having surgery and spending time in a hospital, he recovered.

Death

A group of Russian nobles decided that Rasputin's influence over Empress Alexandra was a threat to the Russian Empire. The group was led by Prince Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and the politician Vladimir Purishkevich. They made a plan to kill him.

In December 1916, they invited Rasputin to Yusupov's Moika Palace in Saint Petersburg. There, in the early morning of December 30, 1916, the group murdered Rasputin. He died from three gunshot wounds. His body was dropped into the icy Little Nevka river.

Aftermath

News of Rasputin's murder spread quickly. His body was found under the ice in the river on January 1, 1917. An autopsy confirmed that he had died from being shot.

Rasputin was buried on January 2 in a private funeral. Only the royal family and a few close friends attended. The Grand Duchesses were very upset by his death. They buried him with an icon that they had all signed.

A few months later, in March 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to give up his throne. Soldiers under the new government dug up Rasputin's body and burned it. They did this so his grave would not become a rallying point for people who supported the old government.

Prominent Children

Rasputin's daughter, Maria Rasputin (born Matryona Rasputina; 1898–1977), moved to France after the October Revolution and later to the United States. In America, she worked as a dancer and a lion tamer in a circus.

See also

In Spanish: Grigori Rasputín para niños

In Spanish: Grigori Rasputín para niños

- Archimandrite Photius, influential and reactionary Russian priest and mystic

- Faith healing

- Rasputin (song)

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |