Robert Charles riots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Robert Charles riots |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | July 23 – July 28, 1900 | |||

| Location |

New Orleans, Louisiana, United States

|

|||

| Caused by | White reaction to killing of policemen | |||

| Goals | Suppression of African Americans; | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

|

||||

| Lead figures | ||||

|

||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Death(s) | 28 | |||

| Injuries | 61 (mostly blacks) | |||

| Arrested | 19 (10 blacks and 9 whites indicted for murder) | |||

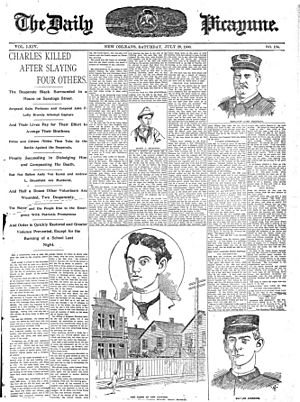

The Robert Charles riots happened in New Orleans, Louisiana from July 24 to July 27, 1900. These events began after African-American worker Robert Charles fatally shot a white police officer. Charles then escaped from the police.

A large search for him started, and a group of white people began rioting. The search for Charles began on Monday, July 23, 1900. It ended when Charles was killed on Friday, July 27.

White rioting continued even after Charles had died. In total, 28 people lost their lives in the riots, including Robert Charles himself. More than 50 people were hurt, and at least 11 needed to be treated in a hospital.

Robert Charles was born around 1865 and came to New Orleans from Mississippi. He taught himself about civil rights and became an activist. He believed that African Americans should be able to defend themselves. He also encouraged African Americans to move to Liberia to escape unfair treatment based on race.

Contents

Understanding the Robert Charles Riots

Life in New Orleans in 1900

Before the American Civil War, Louisiana was a place where slavery was common. Many enslaved people worked on large farms called plantations. Others worked in cities like New Orleans or on steamboats.

By 1900, New Orleans had a population of about 209,000 white people and 77,000 Black people. Among the Black population were many mixed-race individuals. Their ancestors were often known as free people of color before the Civil War. They were also called Creoles of color.

After the Civil War, white leaders in Louisiana passed new laws. In 1898, they created a new state constitution. This constitution made it very hard for most African Americans to vote. They used things like poll taxes and reading tests.

By 1900, the state also passed eight Jim Crow laws. These laws created racial segregation. This meant different facilities for white and Black people. For example, public places like train cars were separated by race.

A famous court case, Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896), came from Louisiana. It was about segregation on trains. The US Supreme Court said states could have "separate but equal" facilities. However, in reality, the "separate" places were rarely equal.

These laws made racial tensions much worse. Historians note that signs of growing anger between races were seen almost daily in New Orleans during June and July 1900. Newspapers in New Orleans also made things worse. They often used very racist language in their articles and opinions.

Racial Attitudes and Segregation

In southern Louisiana, African Americans had sometimes experienced more freedom than in other areas. This was especially true in New Orleans due to its unique history. During the time when France and Spain controlled the area, New Orleans had three main racial groups: white, free persons of color (mixed-race people), and enslaved Black people.

Robert Charles was considered mixed-race. His family might have been free before the Civil War. In French colonial society, free people of color often had more rights. They could get an education, own property, and work in skilled jobs.

After the United States took over Louisiana, especially after the Reconstruction era, more white people from the Protestant South moved in. They tried to force a system where everyone was seen as either Black or white. By the 1900s, strict segregation lines were put in place in New Orleans. This included separating people by race on streetcars.

The Events of the Riots

The First Confrontation

Around 11 p.m. on July 23, 1900, three white police officers investigated a report. They were looking for "two suspicious looking negroes" sitting on a porch. This was in a mostly white neighborhood.

The officers found Robert Charles and his roommate, Leonard Pierce, who was 19. The police questioned them, asking what they were doing. One of the men said they were "waiting for a friend."

Charles then stood up. The police saw this as an aggressive move. Both Officer Mora and Charles pulled out guns and fired shots. Both men were shot in the legs, but their injuries were not life-threatening. Charles then ran away to his home.

The Manhunt and Escalation

Charles was back at his home early the next morning. Police were trying to find him. Captain Day and a police wagon arrived at Charles's home on Fourth Street around 3 a.m. on July 24, 1900.

When the police tried to arrest Charles, he shot at them. He killed Captain Day and Peter Lamb. The other police officers hid in a nearby room, and Charles escaped again. The police then started a large search for him.

On July 24, a crowd of white people gathered on Fourth Street. They left when they were wrongly told Charles had been caught and jailed. On July 25, the acting mayor offered a $250 reward for Charles's arrest. He also asked for peace.

However, New Orleans newspapers, especially the Times-Democrat, blamed the Black community. They called for action against them.

In the days that followed, several riots broke out. Groups of white people roamed the streets. Charles had hidden at 1208 Saratoga Street. He stayed safe there until Friday, July 27.

Police received a tip about Charles's location. They searched the house. As officers got close to Charles's hiding spot under the stairs, he started shooting. Other officers quickly brought in more help. They surrounded Charles and also protected Black residents from the angry white crowd.

A fire captain and other volunteers went to the first floor. They lit a mattress on fire beneath Charles. The smoke forced Charles out of the house. As he tried to escape, he was killed by Charles A. Noiret. Noiret was a medical student and a member of the special police, a group of volunteer citizens.

Aftermath of the Riots

After people learned of Charles's death, white mobs started attacking Black residents again. By the next morning, the special police and state militia had stopped the rioting. They brought the city back under control.

The events in New Orleans were reported across the country. They had effects beyond Louisiana. For example, Lillian Jewett was raising money in Boston, Massachusetts for those injured in New Orleans. The Louisiana Times Picayune newspaper called her efforts "Insane Ravings."

A group of wealthy young white men in New Orleans had formed the Green Turtles the year before. This group required members to promise loyalty to white supremacy and the Democratic Party.

After the Robert Charles riots, white people made racial segregation even stronger and more widespread in Louisiana.

The famous New Orleans jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton talked about the 1900 riot. He shared his memories in a 1938 oral history recorded for the Library of Congress.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |