Robert Lindsay Crawford facts for kids

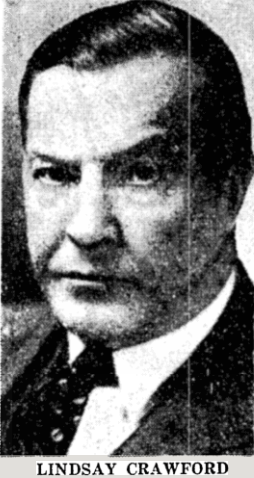

Robert Lindsay Crawford (1868–1945) was an Irish politician and journalist. He started out supporting Unionism and the Orange Order, which wanted Ireland to stay part of the United Kingdom. But over time, his views changed, and he became a strong supporter of an independent Irish Free State. He helped create the Independent Orange Order, hoping to bring Irish people together and support democracy. Later, he worked to gain support for Irish independence in Canada. He also served the new Irish government as a trade representative and consul in New York City.

Contents

Starting the Independent Orange Order

Lindsay Crawford was born in Lisburn, County Antrim, Ireland, on October 1, 1868. He worked in business for a while. In 1901, he became the first editor of a newspaper called Irish Protestant in Dublin. This paper often spoke out against the government at the time.

In 1903, Crawford and Thomas Sloan, a Member of Parliament, started the Independent Orange Order (I.O.O.). This new group was a protest against the main Orange Order. Crawford felt the main Orange Order was too controlled by the Ulster Unionist Party and only cared about landlords and employers. He had even been kicked out of the main Orange Order.

Crawford wanted the I.O.O. to be "strongly Protestant, strongly democratic," and "strongly Irish." He believed it was a movement for ordinary people against the old-fashioned system that had been in Ireland for a long time. In 1904, he wrote a book explaining the new group's goals.

He also asked Irish Protestants to think about their role as Irish citizens. He wanted them to improve their relationships with their Catholic neighbors. However, these ideas caused a disagreement with Sloan and other members who were more focused on staying part of the United Kingdom.

A Voice for Change

Crawford found some friends in the south of Ireland who also wanted change. These included a writer named James Owen Hannay and leaders of the Gaelic League, like Douglas Hyde. They also included Arthur Griffith, who helped start the Sinn Féin movement. Hannay thought the Independent Orange Order was similar to the Gaelic League because both were democratic and not controlled by rich people.

Crawford believed that Irish people needed to focus on practical things like jobs and money, not just language and culture. He thought that if people were hungry, they needed "bread," not just "language and culture."

He also worried that Home Rule (Ireland governing itself) might lead to "Rome Rule," meaning the Catholic Church would have too much power. However, he also said that religious leaders, both Protestant and Catholic, sometimes stopped Irish people from truly uniting. He believed this made it easier for English politicians to control Irish votes.

Crawford felt that religious control over education was a big problem in Ireland. He wanted the government to control schools, not churches. Some people, like Michael Davitt, agreed with him. But this idea was not popular with most Irish nationalists. Even Crawford's own church did not support his ideas for reform.

Changing Political Views

In 1906, Crawford had to sell his newspaper, Irish Protestant. The new owners did not agree with his growing support for Irish independence and workers' rights. One of his last articles praised Michael Davitt, a leader who fought for land rights and supported state education. Crawford saw Davitt as a "great apostle of democracy."

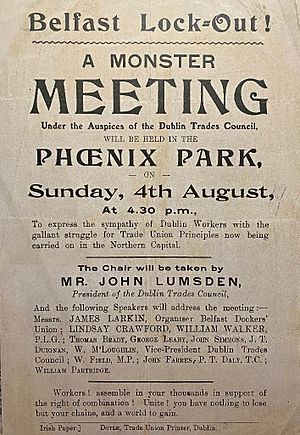

Crawford also supported workers during the Belfast dock strike and lockout in 1907. He spoke at public meetings with James Larkin, a union leader. Crawford encouraged workers to stay strong, not just for their own rights, but for the unity of all Irish people.

He became the editor of another newspaper, the Ulster Guardian. But again, his strong views caused problems. He was criticized for supporting workers and for celebrating historical Irish rebels like the United Irishmen. These rebels had fought for an independent Ireland in 1798.

In 1908, Crawford was fired from the Ulster Guardian. The owners did not want the paper to support Home Rule, which meant Ireland governing itself. Around the same time, he was also kicked out of the Independent Orange Order.

By 1910, Crawford had no clear political home in Ireland. He moved to Canada.

Supporting Ireland in North America

From 1910 to 1918, Crawford lived in Canada and worked for a newspaper called the Toronto Globe. After the Easter Rising in 1916 (an attempt by Irish rebels to gain independence), Crawford openly supported Irish self-determination. This put him at odds with his newspaper, which supported Ireland remaining part of the British Empire.

In 1918, Crawford became the first editor of a new paper called the Statesman. In this paper, he wrote articles supporting Irish independence. He also became involved with groups like the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Canada and Newfoundland (SDIL).

In 1920, Crawford spoke in New York City alongside Éamon de Valera, a key leader in the Irish independence movement. Crawford was named the national president of the SDIL. He then went on a speaking tour across Canada. He faced strong opposition from the Orange Order in many places. In some cities, people tried to stop him from speaking or even attacked him.

Crawford argued that the fight for Irish independence was not about race or religion. He wanted "a broader spirit of toleration" in discussing the problems between Ireland and Britain.

Later Life and Family

From 1922, Crawford lived in New York City. He worked for the new Irish Free State government as a trade commissioner and consul until 1929. Later, he became the secretary of the American National Foreign Trade Council. He worked hard to increase trade between Ireland and the United States. He also fought against companies that misused the trade name 'Irish' for their products.

Robert Lindsay Crawford passed away in New York City on June 3, 1945, at the age of 76. He left behind his wife, Edith Church, and three children: Desmond, Morna, and Doris.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |