Ryukyuan music facts for kids

Ryukyuan music, also known as Nanto music, is a name for all the different kinds of music found in the Amami Islands, Okinawa Islands, Miyako Islands, and Yaeyama Islands. These islands are located in southwestern Japan. Experts often prefer the name "Southern Islands" music because it covers a wider area.

The word "Ryūkyū" first referred mainly to Okinawa Island. It is strongly connected to the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was a powerful kingdom based on Okinawa Island. This kingdom had its own special "high culture" practiced by the samurai class in its capital city, Shuri. However, scholars who study music from all these islands focus more on the everyday music and traditions of the people, known as folk culture.

How Ryukyuan Music Was Studied

Many different musical traditions from the Southern Islands have been studied in detail. A big project to understand all these traditions was led by Hokama Shuzen and his team. Before their work, studies usually focused on just one island group, like Amami or Okinawa, or even smaller areas.

Early studies on Okinawa's music began in the late 1800s with Tajima Risaburō. Other researchers like Katō Sango and Majikina Ankō followed him. Iha Fuyū, who is known as the "father of Okinawaology" (the study of Okinawa), did a lot of research on many types of Okinawan music. He mostly looked at written texts. He also paid attention to Miyako and Yaeyama, but his studies there were just starting because there weren't many written records available. For Miyako and Yaeyama, important work in collecting and writing down folk songs was done by Inamura Kenpu and Kishaba Eijun.

Hokama Shuzen, who continued Iha Fuyū's work, tried to connect all these separate studies. He compared music from different islands and also did his own research across the entire island chain. He thought it was important to include Amami, which was often left out of stories about Okinawan culture. His many years of research led to important books like Nantō koyō (1971), Nantō kayō taisei (1978–80), and Nantō bungaku-ron (1995).

Types of Ryukyuan Songs

The musical traditions of the Southern Islands are very diverse. It can be hard to see how they are connected at first glance. But Hokama Shuzen found a way to group them into categories that apply across different islands.

Here is a table showing one way Hokama (1993) classified songs from the Southern Islands, with some examples:

| category | subcategory | Amami | Okinawa | Miyako | Yaeyama |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| child-related | warabe-uta | ||||

| lullaby, "humoring" songs | |||||

| ritual, festival, ceremony | ritual | nagare-uta | umui, kwēna | tābi | tsïdï |

| Hirase mankai | amawēda | fusa | mishagu pāsï | ||

| omori | tirukuguchi | nīri | |||

| yungutu | pyāshi | ||||

| community-related events | hachigatsu-odori uta | usudaiko | kuichā | yungutu | |

| mochi morai uta | eisā, shichigwachi-mōi | yotsudake-odori | ayō | ||

| Kyōdara | jiraba | ||||

| yunta | |||||

| hōnensai | |||||

| setsu-matsuri | |||||

| tanetori-matsuri | |||||

| performing arts | Shodon shibai | Chondarā | Tarama hachigatsu-odori | ||

| Yui hōnensai | |||||

| Yoron jūgoya-odori | |||||

| home events | shōgatsu-uta | tabigwēna | yometori-uta | yātakabi | |

| mankaidama | iwai-uta | tabipai no āgu | yomeiri-uta | ||

| gozenfū | iezukuri-uta | iezukuri-uta | nenbutsu | ||

| kuya | nenbutsu | shōgatsu āgu | |||

| work | work songs | itu | sagyō-uta | funakogi āgu | jiraba |

| taue-uta | awatsuki āgu | yunta | |||

| mugitsuki āgu | |||||

| performing arts | Kunjan sabakui | yonshī | kiyari | ||

| entertainment | recreational gatherings (asobi-uta) | shima-uta | myākunī | (kuichā) | fushiuta |

| kudoki | kuduchi | āgu | tubarāma | ||

| rokuchō | tsunahiki-uta | tōgani | sunkani | ||

| kachāshī | shunkani | kudoki | |||

| zōodori-uta | mōya | ||||

| new, popular music | shin min'yō | shin min'yō | |||

| classical music | classical music |

Here is another way Hokama (1995) classified the songs, including chants and plays:

| category | Amami | Okinawa | Miyako | Yaeyama |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| magical | kuchi | miseseru | kanfuchi | kanfuchi |

| tahabë | otakabe | nigōfuchi | nigaifuchi | |

| ogami | tirukuguchi | nigari | takabi | |

| omori | nigēguchi | tābi | nigai | |

| yungutu | ugwan | majinaigutu | yungutu | |

| majinyoi | yungutu | jinnumu | ||

| majinaigutu | ||||

| epic | nagare-uta | kwēna | nagaāgu | ayō |

| hachigatsuodori-uta | umui | kuichā-āgu | jiraba | |

| omoro | yunta | |||

| tiruru | ||||

| lyric | shima-uta (uta) | ryūka (uta) | kuichā | fushiuta |

| tōgani | tubarāma | |||

| shunkani | sunkani | |||

| drama | Shodon shibai | kumiodori | kumiodori | kumiodori |

| kyōgen | kyōgen | kyōgen | kyōgen | |

| ningyō-shibai | ||||

| kageki |

The first group, "magical" songs, are like chants or spells. People sang them believing in kotodama, which is the idea that words have spiritual power. For example, Kume Island in the Okinawa Islands has many old chants used for making rain.

Epic songs tell long stories. Okinawa's kwēna songs describe daily life and work, like fishing, rice farming, building houses, and weaving. Umui songs cover even more topics, such as stories about how things began, metalworking, wars, trade, and funerals. Miyako's āgu songs are famous for telling stories about heroes.

Lyric songs are shorter and have a set verse pattern. Examples include Amami's shima-uta, Okinawa's ryūka, and Miyako's tōgani.

How Ryukyuan Music Changed Over Time

By comparing music across different island groups, experts could study how these musical traditions developed over time. They generally agree that magical chants were the oldest form of music. Epic songs then grew out of these magical chants. Lyric songs were the newest and most creative form, developing from epic songs.

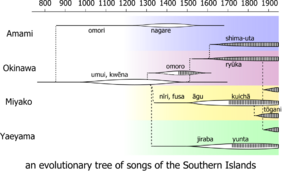

Ono Jūrō created a diagram showing how songs from the Southern Islands evolved. He also carefully studied the different song forms. According to Ono, the oldest song form was a chain of 5-syllable couplets (two lines). You can find this form in the Amami and Okinawa Islands, but not in Miyako and Yaeyama.

From these 5-syllable couplets, a new form with 5-3 syllables (called the kwēna form) appeared. The kwēna form spread from Okinawa to Miyako and Yaeyama. In the Ryukyu Kingdom on Okinawa Island, omoro songs came from the kwēna form around the 14th century. However, omoro quickly became less popular by the end of the 16th century.

Omoro was replaced by ryūka in Okinawa. This ryūka then became shima-uta in Amami. Ryūka has a special 8-8-8-6 syllable pattern. Ono thought this pattern was influenced by kinsei kouta from mainland Japan, which has a 7-7-7-5 pattern. However, Hokama disagreed. He believed ryūka developed within Okinawa itself. Miyako and Yaeyama did not adopt this new ryūka form but created their own lyric songs using the older 5-3 syllable patterns.

After the Satsuma Domain conquered Ryūkyū in the early 1600s, the samurai class in Shuri adopted many parts of mainland Japan's high culture. The name ryūka was created to tell their own uta (songs/poems) apart from waka, which was a type of Japanese poetry. With clear influence from waka, they changed their songs from being sung to being read as poems.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |