Sailing stones facts for kids

Sailing stones are rocks that move across flat, dry lakebeds, leaving long tracks behind them. People also call them sliding rocks, walking rocks, or moving rocks. This amazing natural event happens without any animals pushing the rocks. It occurs when thin sheets of ice, just a few millimeters thick, float on a shallow winter pond. These ice sheets, frozen during cold nights, are then pushed by the wind on sunny days. As the ice moves, it shoves the rocks along the smooth ground. The rocks can move at speeds up to 5 meters (about 16 feet) per minute!

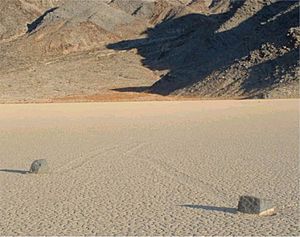

Scientists have seen and studied these moving rocks in different places. The most famous spot is Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park, California. Here, you can see many long tracks left by the stones. Another place is Little Bonnie Claire Playa in Nevada.

Contents

What Are Sailing Stones?

The Racetrack Playa is covered with these special stones, especially in the southern part. Some stones are found quite close to where they broke off from nearby hills. There are three main types of rocks:

- Syenite: These are common on the west side of the playa.

- Dolomite: These are blue-gray rocks with white stripes.

- Black dolomite: This is the most common type. It often looks like sharp, angular pieces. Most stones in the southern part of the playa are black dolomite. They come from a tall hill nearby.

The tracks left by the stones can be very long, sometimes up to 100 meters (about 330 feet). They are usually about 3 to 12 inches (8 to 30 cm) wide. The tracks are often less than 1 inch (2.5 cm) deep. Most of the moving stones are about 6 to 18 inches (15 to 45 cm) across.

How Do the Stones Move?

The way a stone moves depends on its bottom. Stones with rough bottoms leave straight, scratched tracks. Stones with smooth bottoms tend to wander and make curvy paths. Sometimes, a stone might even flip over. This exposes a different side to the ground, creating a new kind of track.

The tracks can go in different directions and have different lengths. Two rocks that start next to each other might move together for a while. Then, one might suddenly turn left, right, or even go back the way it came! The length of the tracks also varies. Two similar rocks might move at the same speed, then one could speed up or stop.

For the stones to move, several very specific things need to happen:

- The ground must be covered in water (flooded).

- There needs to be a thin layer of slippery clay on the ground.

- Strong winds are needed.

- Thin sheets of ice must form on the water.

- The temperature must warm up, causing the ice to break apart.

Studying the Sailing Stones

People have been studying the tracks at Racetrack Playa since the early 1900s. For a long time, no one was sure exactly how the stones moved. Scientists had many ideas. However, in August 2014, something exciting happened. Scientists published a video showing the rocks moving! The video showed the rocks sliding when strong winds blew across thin, melting ice sheets. This confirmed that moving ice, pushed by wind, is what makes the stones slide.

Early Discoveries

The first time someone officially wrote about the sliding rocks was in 1915. A prospector named Joseph Crook visited the Racetrack Playa. Later, in 1948, geologists Jim McAllister and Allen Agnew mapped the area. They wrote the first scientific report about the sliding rocks. They thought strong winds might push the rocks over muddy ground.

Over the years, many different ideas came up, some even supernatural! Most geologists believed that strong winds were involved, especially when the ground was wet. However, some rocks weigh as much as a person. Some researchers, like geologist George M. Stanley, thought these rocks were too heavy for just wind to move. He suggested that ice sheets around the stones might help. The ice could either catch more wind or drag the stones along.

Tracking Stone Movement

In 1972, scientists Bob Sharp and Dwight Carey started a project to watch the stones. They marked 30 stones with fresh tracks and recorded their positions for seven years. They even gave each stone a name!

They tried an experiment with a small fence (a corral) around one stone. They wanted to see if ice sheets helped move the stones. The stone moved right out of the corral, barely missing the fence. This showed that if ice was involved, the ice around the stones must be small.

During their study, 10 of the 30 stones moved in the first winter. Two other winters also saw many stones move. No stones moved in the summer. In the end, almost all the marked stones moved during the seven years. The smallest stone, named Nancy, was only about 2.5 inches (6 cm) wide. It moved the farthest total distance, about 860 feet (262 meters)! The heaviest stone to move weighed about 80 pounds (36 kg).

One very large stone, named Karen, weighed about 700 pounds (318 kg). It did not move during the study. Karen had a very long, straight track from before the study. Karen disappeared sometime before 1994 but was found again in 1996.

New Ideas in the 1990s

In 1995, Professor John Reid and his students continued the research. They found that many stones moved together in groups. This suggested that large sheets of ice, perhaps up to half a mile wide, were moving them. They saw evidence of these moving ice sheets on the ground. So, both wind alone and wind with ice sheets were thought to be important.

In 1996, physicists studied how winds blow over the playa. They found that the smooth, flat surface of the playa can make winds stronger. Also, the layer of slower wind near the ground (called the boundary layer) can be very thin, only about 2 inches (5 cm) high. This means that stones just a few centimeters tall feel the full force of strong winds. Winter storms can have gusts up to 90 mph (145 km/h)! These strong gusts likely start the movement. Then, steady winds keep the stones sliding, sometimes as fast as a person running.

Today, the most accepted idea is that both wind and ice work together to move these sliding rocks. If the ice breaks into smaller pieces, the rocks might take different paths, explaining why some tracks are not parallel.

Climate Change and the Stones

The movement of sailing stones needs a very special combination of events. The dry lakebed needs to be flooded, and it needs to be cold enough for the water to freeze. If winters become drier or warmer, these conditions might happen less often. One study looked at reports of rock movements and suggested that they might be happening less frequently now than they did in the past.

Images for kids

-

A panorama of the Milky Way with the tracks of sailing stones below: Notice the stone on the right side.

See also

In Spanish: Piedras deslizantes de Racetrack Playa para niños

In Spanish: Piedras deslizantes de Racetrack Playa para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |