Santa María School massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Santa María School massacre |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

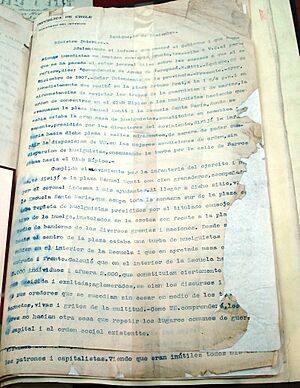

Santa María School of Iquique in 1907 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Chilean workers | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pedro Montt Roberto Silva Renard |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 killed | 300 killed | ||||||

The Santa María School massacre was a terrible event that happened in Iquique, Chile, on December 21, 1907. The Chilean Army attacked striking workers, many of whom were miners from saltpeter works (mines that produced a mineral called sodium nitrate, used to make fertilizer and explosives). Wives and children were also with the workers.

The exact number of people who died is not known, but it is thought to be more than 2,000. This happened when nitrate mining was very important for Chile's economy. The attack stopped the workers' strike and made it very hard for workers to organize for a long time. For many years, the government tried to keep this event a secret. But in 2007, Chile officially remembered the 100th anniversary of the massacre.

The attack happened at the Domingo Santa María School. Thousands of miners from different nitrate mines had gathered there. They had traveled to Iquique, the main city in the region, to ask the government for help. They wanted better living and working conditions. The Minister of the Interior, Rafael Sotomayor Gaete, decided to end the strike, even if it meant using the army.

On December 21, 1907, General Roberto Silva Renard, who was in charge of the soldiers, told the strike leaders that the workers had one hour to leave. If they didn't, the soldiers would shoot. When the hour passed, the leaders and the crowd stayed. General Silva Renard then ordered his troops to fire. First, they shot the leaders. Then, they fired rifles and machine guns into the crowd of workers, their wives, and children.

Contents

Why Workers Protested

Chile faced big problems in the late 1800s. People called it the "social question." This meant that living and working conditions for miners and city workers were getting much worse. The nitrate miners' strike in December 1907 was one of many protests that had started in 1902. Workers in Chile, especially nitrate miners, began to form groups to fight for their rights.

Life in the Nitrate Mines

The region where the nitrate mines were located is called the Norte Grande (Big North). It is part of the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth. Chile took this land from Bolivia and Peru in the War of the Pacific (1879–1884). This gave Chile a lot of valuable minerals, especially copper and nitrate.

Nitrate mining became the most important part of Chile's economy in the late 1800s. Chile was the only country in the world that produced it. In 1907, about 40,000 people worked in the nitrate industry in the Tarapacá and Antofagasta regions. About 13,000 of these workers came from Bolivia and Peru.

Life in the mining camps, called oficinas (offices), was very hard and dangerous. The mine owners controlled everything about the workers' lives. Each oficina was like a small town owned by the mine company. The owner owned the workers' homes, the company store (called a pulpería), and even had their own police force. Workers were paid in special tokens that could only be used at the company store. Sometimes, workers had to wait up to three months to get paid.

Because of these harsh conditions, workers in the nitrate oficinas started to protest. They asked the government in Santiago to help them get better living and working conditions. However, the government usually did not want to get involved. They often saw large worker protests as a threat.

The 18 Pence Strike

On December 10, 1907, a big strike began in the Tarapacá region. It was called the "18 Pence Strike" because workers in one job asked for a wage of 18 pence. Many strikers traveled to Iquique, carrying flags from Chile, Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina. As more workers joined, almost all businesses and industries in the north of Chile stopped.

By December 16, thousands of workers from other industries also came to Iquique. They supported the nitrate miners' demands. Workers had tried to get the government's attention before, in 1901, 1903, and 1904, but nothing had changed.

The government in Santiago sent more soldiers to Iquique. President Pedro Montt put General Roberto Silva Renard in charge. General Silva Renard was secretly told by the Minister of the Interior, Rafael Sotomayor Gaete, to use any means necessary to make the miners go back to work.

More and more workers joined the strike every day. By December 21, it is believed that 10,000 to 12,000 strikers were in Iquique. They gathered in Manuel Montt plaza and at the Santa María School. They wanted the government to help them talk with the foreign (English) nitrate companies. The company bosses, however, refused to talk until the workers returned to their jobs.

The Attack Begins

The acting leader of the Tarapacá region, Julio Guzmán García, tried to help with talks. But then the main leader, Carlos Eastman Quiroga, and General Roberto Silva Renard arrived on December 19. They were cheered by the workers because a past request to the government had seemed hopeful. However, the government did not support the strikers' demands.

The government ordered the strikers to leave the plaza and the school. They were told to go to the horse racing track and take trains back to work. The workers refused. They felt that if they went back to work, their requests would be ignored.

Tension grew between the groups. On December 20, 1907, the workers' leaders met with Intendant Eastman. At the same time, a newspaper announcement said that a "state of siege" was declared. This meant that people's normal rights were temporarily stopped. While the meeting was happening, some workers and their families tried to leave. But soldiers shot at them by the railroad tracks. Six workers died, and others were hurt.

The funerals for these workers were held the next day, December 21, 1907. After the funerals, all workers were ordered again to leave the school and go to the Club Hípico (Horse Club). The workers refused, fearing that warships lined up along the road might attack them.

At 2:30 in the afternoon, General Silva Renard told the workers' leaders that if the strikers did not start going back to work within one hour, the soldiers would open fire. The leaders refused to leave, and only a small group of strikers left the plaza.

At the time General Silva Renard had set, he ordered his soldiers to shoot the workers' leaders. The leaders were on the school's roof and fell dead with the first shots. The crowd, in a panic, tried to escape and rushed toward the soldiers. The soldiers then fired rifles and machine guns into the crowd. After shooting from Manuel Montt plaza, the troops entered the school grounds. They fired machine guns into the playgrounds and classrooms, killing people without caring about the women and children who were crying for help. The people who survived the attack were forced to go to the Club Hípico. From there, they were sent back to work and faced very strict control.

How Many Victims?

The government ordered that no death certificates be given for those who died. The victims were buried in a large grave in the city cemetery. Their remains were not dug up until 1940. They were later reburied in the courtyard of the Legal Medical Service in Iquique.

The exact number of people killed is still debated. General Silva Renard's official report first said 140 dead, then later 195. A doctor who witnessed the massacre, Nicolás Palacios, also gave this number. However, many people think this number is too low because so many workers were present. The highest guess has been 3,600, but this is not confirmed.

What Happened After?

General Silva Renard reported to the government in Santiago, making his own role seem smaller and blaming the strikers. The government's reaction was not very strong.

Improvements for workers came very slowly. It was not until 1920 that basic rules for workers began to be put in place. These included making sure workers were paid in real money and setting a limit on how long a workday could be. General Silva Renard was badly hurt in 1914 when a Spanish anarchist named Antonio Ramón tried to kill him. Ramón's brother had been one of the victims of the massacre. General Renard died a few years later from these injuries.

Remembering the Massacre

For the 100th anniversary of the massacre, a special monument was opened in the local cemetery. The remains of one victim and one survivor were reburied there. Public exhibits were also set up. President Bachelet declared December 21, 2007, a national day of mourning.

Cultural Impact

The government tried to hide the details of the massacre for many years. But over time, its sad story inspired singers and poets. People also started to study its social effects from the mid-1900s onward. Some important artistic and academic works include:

- Books

- 1915 – Francisco Pezoa, Canto a la Pampa

- 1952 – Volodia Teitelboim, Hijo del salitre, a novel.

- 2002 – Hernán Rivera Letelier, Santa María de las flores negras.

- Music

- 1970 – Luis Advis, Cantata de Santa María de Iquique. (performed by Héctor Duvauchelle and Quilapayún)

- 2009 – Luis Advis, Cantata Rock de Santa María de Iquique. (performed by Colectivo Cantata Rock)

- 2011 – Diablo Swing Orchestra, Justice for Saint Mary

- Theater

- 2004 – La Patogallina group, 1907.

- 2007 – Teatro del Oráculo group, Santa María de Iquique: La Venganza de Ramón Ramón.

- Film

- 1975 – Humberto Solás, Cantata de Chile

See also

In Spanish: Matanza de la Escuela Santa María de Iquique para niños

In Spanish: Matanza de la Escuela Santa María de Iquique para niños

- Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works

- List of massacres in Chile

- Marusia massacre

- Forrahue massacre

- Santa María de Iquique (cantata)

- List of saltpeter works in Tarapacá and Antofagasta

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |