Siege of Basing House facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Basing House |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

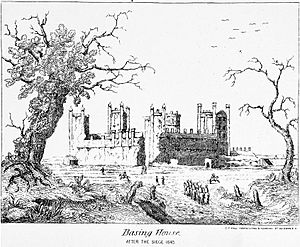

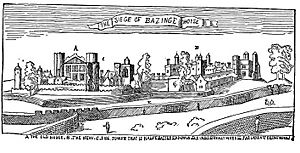

Basing House after the siege |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

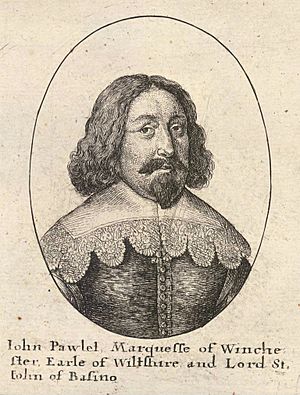

| John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester | Oliver Cromwell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 7,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 killed | 2,000 killed | ||||||

The Siege of Basing House was a series of battles during the First English Civil War. It took place near Basingstoke in Hampshire, England. This conflict was a big win for the Parliamentarian side. Even though it's called "the siege," there were actually three main attacks on Basing House.

John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester owned Basing House. He was a strong supporter of King Charles I, known as a Royalist. He made his home a military base to help the King. Basing House was important because it controlled a key road from London to the west.

Contents

The Story of Basing House

Basing House was once a grand home. It was built by William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester. He changed it from a old castle into a huge, fancy residence.

The house was round and had strong brick walls. It also had a very deep, dry ditch around it. A tall gatehouse with four towers faced north. The whole area, including gardens, covered about 14 acres.

The siege started in August 1643. The owner, John Paulet, hoped to live peacefully there. But he had to defend his home. He and his men, armed with muskets, fought off two early attacks. On July 31, 1643, King Charles I sent 100 soldiers to help defend the house. These troops arrived just hours before another attack, which was also stopped.

The Marquess became a Colonel and Governor of the house. He worked to make its defenses even stronger. He knew that a strong Parliamentarian force was heading his way.

Famous People at Basing House

Many famous people stayed at Basing House during the siege. Some were soldiers, others were refugees from London. William Faithorne, a skilled engraver, was there. So was Wenceslaus Hollar, another famous engraver.

Inigo Jones, a great architect, also found shelter there. Thomas Fuller, who wrote "Worthies of England", was working on his book during the siege. He often had to stop because of the cannon noise. Another person, Lieut.-Colonel Thomas Johnson, a botanist, died at Basing House. Captain William Robbins, a well-known actor, was also killed during the siege.

Getting Supplies

The defenders often ran low on ammunition and food. The King sent supplies, like gunpowder and bullets. In October 1643, the King ordered 10 barrels of powder to be sent.

The Marquess wrote to Lord Percy, asking for carts to carry the powder. He also asked for 100 muskets. He said they desperately needed supplies because the enemy was close.

Sir William Waller was a very active Parliamentarian leader. He was put in charge of a new army in November 1643. He quickly moved to besiege Basing House. The house was important because it controlled a key road to the west.

First Attack

On November 6, 1643, Waller's army, with 7,000 soldiers, surrounded Basing House. They stayed for nine days. During this time, they tried three times to storm the house. Each time, they were pushed back with heavy losses. Only two of the defenders were killed in these attacks.

Waller's first attempt failed due to bad weather. His second attempt failed because his soldiers were not paid. They became rebellious. On November 12, a regiment refused to obey orders. Two days later, London soldiers shouted "Home! home!" and left. Waller could not continue the siege. He had to retreat to Farnham. After this, the King's troops helped strengthen the house's defenses.

During the winter, not much happened. The house was still short on weapons. In February 1644, the King sent more powder and "brown bills" (a type of weapon). In May 1644, he sent more match and muskets.

The 1644 Plot

In early 1644, Lord Charles Paulet, the Marquess's brother, was in charge of Basing House. Some in London believed he would betray the house.

Sir Richard Grenville was part of the Parliamentarian army. He was known for being selfish. He had fought in Ireland and then joined the Parliamentarians. He became a high-ranking officer. But on March 3, 1644, he secretly went to Oxford, a Royalist stronghold. He told them about Paulet's plan to betray Basing House.

Paulet was arrested and faced a military trial. However, the King pardoned him. The King did not want to punish the brother of such a loyal supporter.

Second Attack

In spring 1644, the Parliamentarians changed their plan. Since they couldn't take the house by storm, they decided to try to starve the defenders out. They placed troops in nearby towns like Farnham and Basingstoke. These troops stopped food from reaching Basing House.

On June 4, Colonel Richard Norton arrived. He used Parliamentarian troops to surround Basing House closely. He wanted to force the defenders to surrender by cutting off their supplies. He had defeated some defenders two days earlier. His soldiers stayed in Basingstoke at night, watching all roads to the house.

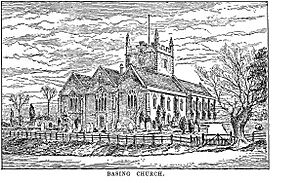

On June 11, more Parliamentarian regiments arrived. They set up camp around the house. On June 17, they took over and fortified the nearby church. They shot two defenders from there. The Marquess divided his few defenders into three groups. Two groups were always on duty. Officers were assigned to different parts of the house.

On June 18, the defenders made a surprise attack. They burned several enemy buildings that were firing at them. They quickly retreated when the enemy sounded an alarm.

On June 29, the Parliamentarians placed their first cannon. They fired six shots from a culverin (a type of cannon). The next morning, they fired from a demi-culverin (a smaller cannon). But a shot from the house quickly silenced it.

In July, Colonel Morley sent a message to the Marquess. He demanded that Basing House be given to Parliament. The Marquess replied, "I keep the House in the right of my Sovereign, and will do it in despight of your forces." He refused to surrender.

The siege continued with great force. By late August, the defenders were running out of food. Some soldiers tried to leave. The Marquess made an example of one, which stopped others from trying for a while.

On September 2, Norton sent another demand for surrender. The Marquess replied that he would not surrender without the King's direct order.

The fighting became even more intense. Cannons fired daily, and many defenders were killed. Famine also weakened them. The King had promised help by September 4. But it wasn't until September 11, 1644, that news arrived that help was on the way.

Gage's Relief Mission

The Royalists decided to send a relief force from Oxford. Colonel Henry Gage led this mission. It was a long journey of about 40 miles. Gage used a trick: he wore an orange sash, which was usually worn by Parliamentarian officers. He hoped his column would look like enemy troops from a distance.

Gage was supposed to meet Sir William Ogle near Basing House. But Ogle sent a message saying he couldn't send his troops.

Gage had to rely on his own forces. After a tough fight, they reached Cowdery's Down. Despite being tired, they broke through the enemy lines. The defenders of Basing House also made a strong attack from inside. Attacked from both sides, the Parliamentarians quickly moved away. Gage entered the house, bringing much-needed ammunition.

The attackers were in disarray. Gage used this chance to gather food for the defenders. Then, 100 musketeers from the house attacked the enemy's positions, including the church. They captured the soldiers inside. The Roundheads' camps were set on fire that night.

The next day, September 12, Gage tricked the besiegers. He ordered food from nearby villages, making them think he would stay. But that night, Gage and his men quietly left. They crossed rivers and reached Wallingford safely. The next day, he returned to Oxford. He had lost only 11 men. For this brave act, he was knighted by the King.

The Siege Continues

After Gage left, Waller's troops quickly surrounded Basing House again. They retook Basing Church. The siege continued with new energy.

The defenders made many surprise attacks. They destroyed enemy positions and seized food. By November, they were running very low on food. The officers were eating only one meal a day. For two weeks, they survived on whatever they could get from their attacks.

Gage's Second Relief Mission

The King heard about their desperate situation. He ordered Sir Henry Gage to relieve Basing House again. The King marched his own troops towards Hungerford to distract Waller. Waller's army was tired and reduced by disease. He decided to move his troops to winter quarters.

On November 15, Waller's soldiers burned their huts and left. The defenders, though weak, attacked the retreating enemy. They caused great disorder.

On November 19, Gage set out again. He had 1,000 horse soldiers. Each carried a sack of corn and other supplies. The next night, Gage arrived at the house. He found no enemy to fight. Gage rode into Basing House, bringing great joy to the defenders.

The following winter and summer were quiet. The defenders repaired the house and gathered supplies for the next attack.

Final Attack

Meanwhile, the King's cause was failing. Oliver Cromwell had won major battles. Many Royalist strongholds had surrendered. Cromwell was ordered to clear the road to London. On September 21, 1645, he captured Devizes Castle.

From Winchester, Cromwell marched to Basing House. Colonel John Dalbier had been besieging it for weeks. Cromwell arrived on October 8, 1645. He brought powerful cannons, including a 63-pounder. He hoped these heavy guns would succeed where others had failed.

On October 11, Cromwell was ready to fire. He demanded the defenders surrender. He saw the house as a "nest of Romanists" (Catholics) who were fighting against Parliament. He warned that if they refused to surrender now, they would not be offered mercy again.

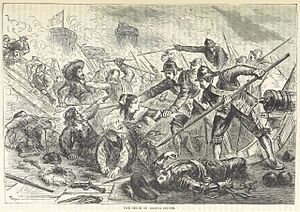

The defenders refused to give up. They did not think Cromwell's heavy guns were a big threat. By the evening of October 13, two large holes were made in the defenses. At 2 AM, it was decided to storm the house at 6 AM. Cromwell spent part of the night in prayer. He believed he was fighting for God against evil.

At the planned time, the attacking soldiers rushed into the house. The defenders were too few to stop them.

No mercy was given until the whole house was captured. Many defenders were killed.

After the fighting, the soldiers looked for treasure. Gold, jewels, and tapestries were taken. Survivors were stripped of their clothes. Old Inigo Jones was carried out wrapped in a blanket.

The stolen goods were said to be worth a huge amount of money. Cromwell's chaplain, Hugh Peters, said one bed alone cost £1,300. Peters presented the Marquess's flag to Parliament. It had the motto: "Donee pax redeat terris" ("until peace return to the earth").

During the chaos, the house caught fire. The flames spread quickly. Only the burned walls remained. Before it was too late, some goods were saved. Local people came to buy food like cheese and bacon that had been stored there.

Reports on the number of dead vary. Some say 300 were captured and 100 killed. Others say about 200 were captured, and 74 men and one woman were found dead. More may have died in the fire.

The Marquess himself survived because he had treated a Parliamentarian officer, Colonel Hammond, kindly when Hammond was his prisoner. Hammond now protected the Marquess. But soldiers still stripped the Marquess of his expensive clothes. The Marquess was asked if he now saw his cause was hopeless. He proudly replied, "If the King had no more ground in England but Basing House, I would adventure as I did, and so maintain it to the uttermost. Basing House is called Loyalty." He hoped the King would have another chance.

Cromwell wrote a detailed letter about the attack on October 14, 1645. He described how his forces attacked from different sides. He mentioned that many of the enemy were killed. He also said that the Marquess and other officers were captured. Cromwell recommended that the house be completely destroyed. He then moved west to join another army.

What Happened Next

It is said that the Marquess had written "Aymez Loyaute" (Love Loyalty) on the windows of the house. This became his family's motto.

Cromwell suggested that Basing House be completely destroyed. On October 15, 1645, Parliament ordered it. Anyone who wanted stones or bricks from the house could take them for free.

Nearby Areas

The town of Basingstoke was also affected by the long siege. Basingstoke Church still has bullet marks on its walls. This shows that soldiers used the church for shelter during battles.

A Parliamentarian committee met in Basingstoke in July 1644. But they fled when Gage's relief force approached.

Records show that Royalist troops often occupied Basingstoke. Parliamentarian troops also used the town. In November 1643, soldiers rested and dried their clothes in Basingstoke after hard fighting. They returned to the town again after a failed attack due to bad weather.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |