Siege of Pamplona (1813) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Pamplona (1813) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Peninsular War | |||||||

Part of the Pamplona fortress. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,500–14,183, 12 guns | 3,450–3,800 80 heavy & 54 field guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 | 3,450–3,800, all guns | ||||||

The Siege of Pamplona happened from June 26 to October 31, 1813. It was a key event during the Peninsular War, which was part of the larger Napoleonic Wars. In this siege, Spanish and British forces surrounded the city of Pamplona in northern Spain. They aimed to force the French soldiers inside to surrender.

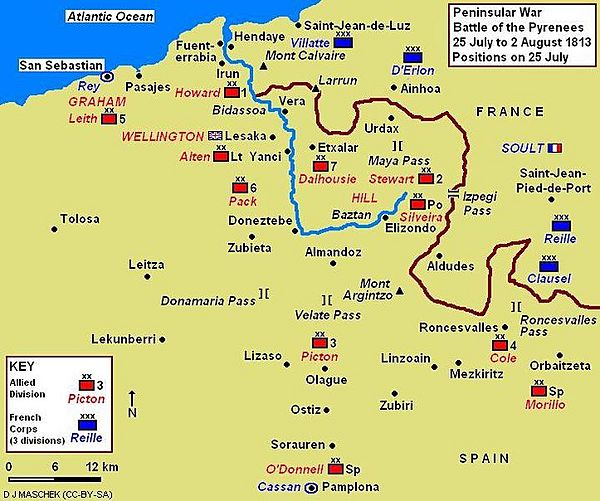

The French garrison, led by General Louis Cassan, was trapped. At first, troops under Marquess Wellington (a British commander) surrounded the city. Soon, Spanish units took over the blockade. In July 1813, French Marshal Nicolas Soult tried to rescue the city, but his efforts failed in the Battle of the Pyrenees. The French soldiers in Pamplona eventually ran out of food and had to surrender.

Contents

Why Pamplona Was Important

After a big victory at the Battle of Vitoria on June 21, 1813, Marquess Wellington pushed the French army out of northern Spain. The defeated French soldiers, led by Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, passed by Pamplona. They were not allowed into the fortress because the French commander there feared they would eat all the food.

British cavalry and infantry arrived at Pamplona on June 25 or 26. Wellington wanted to surround the city completely. However, he also saw a chance to chase another French group. So, some British divisions left Pamplona to pursue the French. Other British divisions were ordered to stay and block the city.

Wellington could have chased the French into southern France. But he had several reasons not to. One big reason was that Russia and Prussia had signed a temporary peace with Napoleon. Wellington did not want to gain land in France only to have to give it back. Also, the British and Portuguese armies had problems with supplies and soldiers leaving their posts.

Before the Battle of Vitoria, four French divisions were far away. They were trying to find Spanish fighters led by Francisco Espoz y Mina. These French troops were not available to help the main French army against Wellington. They only arrived near Vitoria a day after the big battle. Realizing the situation, the French general quickly retreated. Wellington then ordered his troops to chase this French group.

The Siege Begins

Early Days: June to July

After chasing the French for a few days, Wellington stopped on June 29. He turned his divisions back towards Pamplona. Some British and Portuguese troops left Pamplona in early July. This left other British divisions to continue the blockade.

Wellington then ordered Spanish troops to take over the blockade. These Spanish soldiers, led by Henry O'Donnell, had recently won a victory at Pancorbo. They arrived at Pamplona on July 12. This allowed the British divisions to move on to other battles. O'Donnell's force had over 14,000 soldiers.

The French commander, General Cassan, had about 3,800 soldiers and 80 heavy cannons in Pamplona. He also had 54 field guns. A supply convoy had arrived in June with enough food for 2,500 men for 77 days. When the defeated French army passed Pamplona, they sent their sick and unfit soldiers into the fortress. Cassan also organized hundreds of scattered soldiers into a new group.

The Allied forces built nine small forts, called redoubts, around Pamplona. These were about 1,200 to 1,500 yards from the city walls. Each redoubt had 200-300 men and cannons captured at Vitoria. Wellington did not send his heavy cannons to Pamplona. Those were needed for the Siege of San Sebastián.

The Spanish blockade was very effective. They set up an inner line of guards close to the city. An outer line included fortified villages and the new redoubts. No messages could get through to the French garrison from Marshal Soult.

On July 26, the French garrison heard fighting in the distance. This was a skirmish between French and Allied forces. The next day, more Allied divisions appeared near Pamplona. This showed that French forces might be close. O'Donnell's Spanish division left Pamplona to join the other Allies. This created a brief chance for Cassan to escape. But he wanted to hold the city for Soult's army, so he stayed.

On July 27, Cassan tried to attack the Allied defenders outside the city, but it failed. That night, French campfires were seen about 5 miles away. The Battle of Sorauren began on July 28, but no French troops reached Pamplona. Another Spanish division arrived to fill the gap on the south side of Pamplona. On July 30, more battle sounds were heard, but they moved away. It became clear that Soult's army was retreating.

Later Stages: August to October

Even though the French relief effort failed, Cassan kept his soldiers fighting for three more months. The Spanish sent messages to the garrison. They announced Allied victories at the Battle of San Marcial and the Battle of the Bidassoa. This was to show the French that their situation was hopeless. But Cassan decided to hold out until all the food was gone.

The land near Pamplona was very fertile. It had many wheat fields and gardens. From July to September, Cassan sent out groups of soldiers to gather food. These groups would suddenly attack the Spanish guards. They would harvest wheat or dig up potatoes. When more Spanish soldiers arrived, the French would retreat back into Pamplona with the food they had found.

On September 9, the Spanish commander, de España, was wounded during one of these food-gathering skirmishes. After there were no more crops, Cassan sent out groups to find firewood and animal feed. By the end of September, the French soldiers were on half-rations. Cassan tried to send the civilians out of Pamplona, but de España ordered his men to fire on them. The civilians had to go back into the city.

The French soldiers became desperate. They killed and ate all the horses. Then they ate dogs, cats, and rats. They even dug up roots, but some of these turned out to be poisonous. By October, 1,000 men were sick in the hospital, many with scurvy (a disease caused by lack of vitamin C). Soldiers from other countries, like Germans and Italians, started leaving the city. Cassan finally sent an officer to discuss surrender on October 24.

Surrender and Aftermath

Cassan first suggested that he and his soldiers be allowed to march out with their cannons and belongings. He wanted to join Soult's army. But de España demanded an unconditional surrender. Cassan then threatened to blow up the Pamplona fortress and fight his way to the French border. He later admitted this was a bluff. His starving soldiers could barely march a few miles.

De España responded by saying there were 25,000 Allied soldiers between Pamplona and the border. He warned that if the French blew up the fortress, his men would take no prisoners. He also said that local farmers would likely kill anyone who escaped. Wellington even wrote a letter saying that French officers should be shot and common soldiers punished severely if they damaged the city.

Cassan then offered that his soldiers would not fight against the Allies for a year and a day. De España refused, saying France often did not keep such promises. Finally, Cassan had to accept the terms. His soldiers were allowed to march out with military honors. But they had to lay down their weapons about 300 yards from the gates. They would then be sent to prison camps in England. Sick soldiers were also prisoners. French civilians could go free, but Spanish people who had helped the French were handed over to the Spanish. Some of these were executed.

Historians say that about 500 French soldiers were killed, 800 wounded, and 2,150 captured. The Spanish forces, numbering around 9,500, had about 2,000 casualties.

Wellington thought the Spanish blockade was not strict enough. He believed that if the wheat fields had been burned, Pamplona would have fallen three weeks earlier. Cassan's ability to hold out for so long forced Wellington to keep troops in the Pyrenees. These soldiers suffered from constant rain and snow, and many ended up in the hospital. More importantly, Wellington refused to move his army into France until Pamplona had fallen. So, Cassan's long defense was helpful to his emperor.

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Pamplona (1813) para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Pamplona (1813) para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |