Star Canopus diving accident facts for kids

| Date | 26 November 1978 |

|---|---|

| Location | Beside Beryl Alpha platform, Beryl oil field, East Shetland Basin, North Sea, Scotland |

| Cause | Diving bell lift wire and umbilical severed |

| Participants | Ed Hammond, Robert Kelly, Lothar Michael Ward, Gerard Anthony "Tony" Prangley |

| Outcome | Deaths of Ward and Prangley |

The Star Canopus diving accident happened in Scotland in November 1978. It was a sad event where two British commercial divers lost their lives. They were working near the Beryl Alpha oil platform in the North Sea. Their diving bell was connected to a ship called MS Star Canopus.

During a routine dive, the diving bell suddenly broke free. Its main lift wire, life support cable (called an umbilical), and guide wires were cut. This happened because an anchor chain from another large ship, the Haakon Magnus, severed them. The bell then fell to the seabed, which was more than 100 metres (330 ft) deep.

Inside the bell were two divers: 25-year-old Lothar Michael Ward and 28-year-old Gerard Anthony "Tony" Prangley. They tried to release the bell's emergency drop weight to float back to the surface. But they couldn't because the weight was held by extra safety pins on the outside of the bell. The bell didn't have a special platform (called a bell stage) to keep its bottom door off the seabed. This meant the divers couldn't open the door to get out and release the pins.

Three rescue ships – Intersub 4, Tender Carrier, and Uncle John – tried to help. But it took over thirteen hours to bring the bell back up. By then, Ward and Prangley had died from hypothermia (being too cold) and drowning.

What Happened Before

On November 26, 1978, the ship Star Canopus was being used for diving. It was holding its position using special computer systems (this is called dynamic positioning). The ship was on the northeast side of the Beryl Alpha oil platform.

About 334 feet (102 m) below the surface, diver Michael Ward was working. He was about 60 feet (18 m) above the seabed. His job was to connect a 6-inch (150 mm) pipe to a part sticking out from the side of the platform.

That year, oil production had slowed down. Winter weather was also making underwater work difficult. Companies like Mobil Oil wanted to catch up on their work. So, they decided to let diving continue through the winter when the weather allowed.

Earlier that evening, the weather forecast warned of strong winds. They expected gusts of up to 40 knots (74 km/h) between 6 PM and midnight. The forecast was right. Around 8:30 PM and again at 10:45 PM, strong winds hit. These winds blew the Canopus off its planned spot. Because of this, Captain Roy Forsyth stopped the diving work.

But at midnight, when the next shift started, the weather had calmed down. The new supervisor, Robert Kelly, was told to continue diving. This was because conditions had improved.

The new weather forecast said the wind would change direction. It would blow from the north and get worse later in the day. Winds could reach 35 knots (65 km/h). The Canopus was a new ship, only a year old. It had the best technology for its time. But its dynamic positioning system could only handle winds of 18–20 knots (33–37 km/h) if the wind hit the ship from the side.

The Accident and Rescue

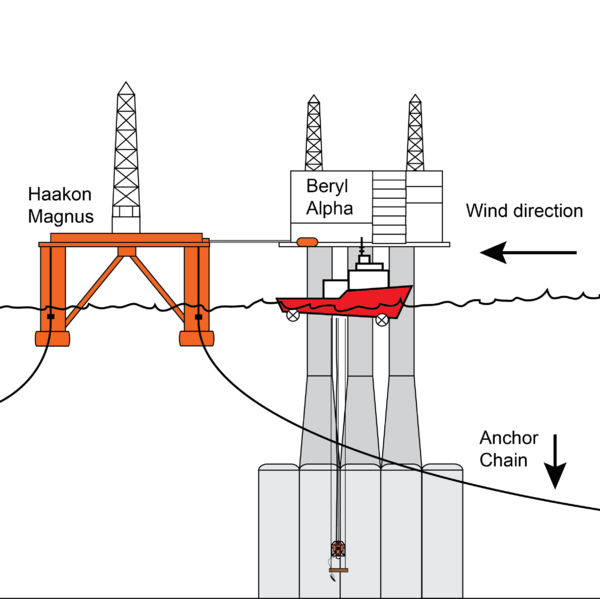

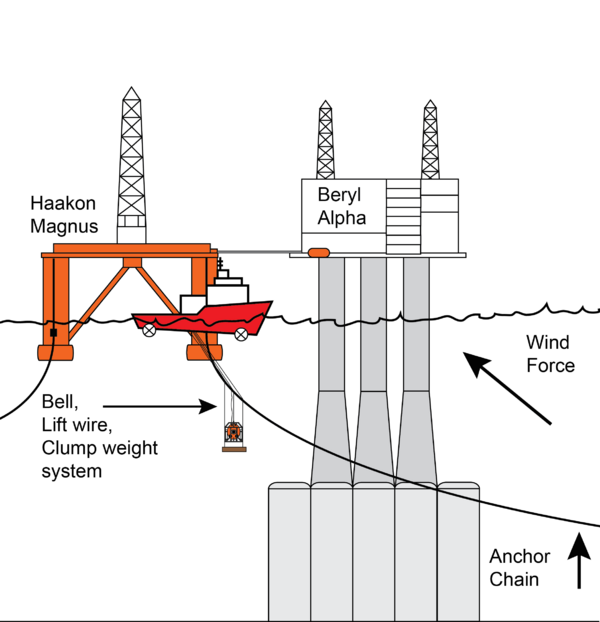

Before the accident, the wind speed was changing between 15–20 knots (28–37 km/h). Near the Beryl platform, where the Canopus was about to start work, was another ship. This was the Haakon Magnus, a large Norwegian semi-submersible platform. Its huge anchor chains were spread out.

Supervisor Kelly decided the weather was good enough for diving. At 2:40 AM, he sent the diving bell down. Tony Prangley and Michael Ward were inside.

At 3:12 AM, Ward left the bell. He found the pipe part sticking out from the platform wall. Eight minutes later, Captain Forsyth told Kelly that a storm was coming. Kelly ordered Ward to go back into the bell. Ward stayed there for the next 40 minutes. At 4:00 AM, Ward went back to work.

Then, at 5:45 AM, the wind suddenly changed direction. It started blowing from the north at 40 knots (74 km/h). This wind hit the Canopus from the side. It was too strong for the ship's dynamic positioning system. The wind kept blowing strongly for a long time.

In the dive control room, Supervisor Kelly saw a warning light and heard an alarm. Captain Forsyth ordered the divers to return to the bell. Kelly told Ward to stop working and swim back to the bell. Inside the bell, Ward took off his helmet. Prangley started to coil Ward's life support cable.

On the surface, the strong wind pushed the Canopus sideways. It crashed against the platform. The ship's mast broke off and fell onto the deck. At the same time, the wind pushed the ship backward towards the Haakon Magnus. Captain Forsyth quickly turned off the dynamic positioning. He tried to turn the ship's front away from the Magnus. He also pressed the 'Dive Abort' alarm and called dive control.

In dive control, Kelly was waiting for Prangley and Ward to close the bell door. Suddenly, the red 'Dive Abort' light came on. Captain Forsyth again told Kelly that the divers needed to get back into the bell. But when Kelly called the bell, Prangley said he was having trouble. Ward's life support cable was caught on something outside the bell. They couldn't close the inside door until it was free. Ward wanted to go out to fix it, but Kelly said no. Instead, he told Ward to throw his dive helmet out of the bell and then pull in the cable. But it was still stuck.

Meanwhile, Kelly got another urgent message from Captain Forsyth. He asked if the bell was being brought up yet. Kelly explained the problem. He told the divers to stop trying to free the cable and to cut the hose quickly. A few minutes later, the bell hit the base of the platform. Prangley and Ward managed to seal the bell and told the surface.

In dive control, Kelly was watching the two divers on a video screen as the bell was being lifted. Prangley was calling out the depth every 10 metres (33 ft). When the bell was 30 metres (98 ft) from the surface, Prangley suddenly stood up. He waved his fist and shouted, "All stop." On the screen, he looked like he was listening to something.

Supervisor Kelly stopped the bell. From dive control, he could see the moonpool (the opening in the ship where the bell goes down). He saw that something was wrong. The bell's life support cable and guide wires were not hanging straight down. They were leaning towards the front of the ship. Also, the trolley holding the wires was shaking a lot. Then, Kelly lost the video feed from the divers.

The Star Canopus had been blown across the path of an anchor chain from the Haakon Magnus. This chain completely cut all connections to the bell. This included the life support cable, the main lift wire, and the guide wire system. At that moment, the bell, with Prangley and Ward inside, began to fall quickly to the seabed.

Both divers survived the 294-foot (90 m) fall. But their hot-water supply was cut off. The temperature inside the bell started to drop very fast. If rescuers didn't arrive soon, the divers' only way to get to the surface was to release the emergency drop weight. However, Prangley and Ward could not release this weight. It was held by "secondary locking pins" on the outside of the bell. The bell did not have a platform (stage) to keep its bottom hatch off the mud. So, Prangley and Ward had no way to get out and release the pins. The bell also didn't have a flashing light to help rescuers find it in the dark. Plus, the crew of the Canopus had removed the bell's tracking device (transponder) before the dive.

Rescue Efforts

A storm was happening on the surface. It took rescuers more than thirteen hours to bring the damaged bell back to the deck of the Canopus. By that time, Ward had died from hypothermia (being too cold). Prangley had drowned.

Other Accidents to Learn From

- Wildrake diving accident – a similar accident in 1979 where divers also died.

- Stena Seaspread diving accident – a similar accident in 1981, but no one died.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |