Wildrake diving accident facts for kids

| Date | August 8, 1979 |

|---|---|

| Location | Thistle oil field, East Shetland Basin, North Sea, Scotland |

| Cause | Lift wire separated from diving bell |

| Participants | Richard Arthur Walker, Victor Francis "Skip" Guiel Jr. |

| Outcome | Recovery of bodies of Walker and Guiel |

| Inquiries | Fatal accident inquiry (Scotland), May 11–21, 1981 |

| Trial | Crown v. Infabco Diving Services, Ltd. |

| Litigation | Wrongful-death lawsuits, United States and Scotland |

The Wildrake diving accident happened in Scotland in August 1979. Two American commercial divers died during this event. While they were doing a normal dive in the North Sea, their diving bell broke free. It was over 160 metres (520 ft) deep. The ship, MS Wildrake, eventually got the bell back. But the two divers inside, Richard Arthur Walker (32) and Victor Francis "Skip" Guiel Jr. (28), died from hypothermia (being too cold). This accident led to important safety changes for divers.

Contents

What Happened Before the Dive?

Setting Up the Oil Field

In 1977, a special system was put in place at the Thistle oil field. It was called a Single Anchor Leg Mooring (SALM). This system helped oil tankers load oil. It had a buoy (a floating marker) and a pipe (riser) connected to a base on the seafloor.

By early 1979, the buoy had partly come loose from the pipe. The company in charge, British National Oil Corporation (BNOC), used explosives to free the buoy. It was then sent for repairs. But the explosives also damaged the pipe. Divers later removed the damaged pipe. It was taken away for fixing.

Getting the Diving Ship Ready

The MS Wildrake was a ship built for diving support. It belonged to a Norwegian company. It had a special saturation diving system inside. This system was made by another Norwegian company.

In May 1979, a diving company called Infabco Diving Services Ltd. started talking about using the Wildrake ship. In June and July, Infabco workers got the ship's diving system ready. Experts checked and approved the system in July 1979. Later that month, divers used the Wildrake for 17 dives. They were getting the SALM base ready to be put back together.

Changes to the Diving System

During this time, some important changes were made to the diving system.

- The part that connected the main lift wire to the bell was changed.

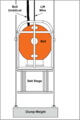

- A heavy weight, called a clump weight, was removed from under the bell. This weight was a backup way to get the bell back up. It was removed so the bell could be launched from the side of the ship, not through a hole in the middle.

- The bell also had drop weights. These were another way to bring the bell to the surface in an emergency. They were tied down with rope. This was to stop them from accidentally falling off. Accidental release of these weights had caused deadly accidents before.

- The Wildrake bell also did not have a special platform (bell stage). This platform usually keeps the bottom door of the bell out of the mud if it lands on the seabed.

The Accident Happens

In late July and early August 1979, divers from the Wildrake put the SALM buoy back onto its pipe. They also got the SALM ready to be moved to the Thistle oil field.

On the night of August 7, 1979, Richard Walker and Victor Guiel were diving. They had been living in a special high-pressure chamber (saturation) since July 29. They were lowered 485 feet (148 m) deep in the Wildrake diving bell. Their job was to work on putting the SALM back on its base. This was their 30th dive from the Wildrake. As the bell went down, a tracking device (transponder) came loose. The ship's foreman was told to cut it off.

Shortly after 2:20 AM on August 8, Walker was working outside the bell. He saw that the bell had broken free from its main lift wire. It was hanging at an angle by its life support cable (umbilical). He quickly reported the problem. Then he went back into the bell with Guiel. They closed the inside door. The bottom door was left open and tied back.

The dive supervisors thought the umbilical was a safe backup way to lift the bell. But the company that designed the system later said it wasn't. Also, the umbilical winch was not approved for lifting the bell. The supervisor tried to lift the bell using the umbilical. But the umbilical was already damaged. It got stuck in the ship's lifting wheel. Another try to lift the bell with the ship's crane damaged the umbilical even more. Power and hot water to the bell stopped. After a faint radio message from the divers, the Wildrake crew lowered the bell to the seabed. It was 522 feet (159 m) deep.

Trying to Rescue the Divers

Another diving ship, the Stena Welder, came to help. Its diving system was being fixed, so it had to be quickly prepared. The rescue team decided to use the Wildrake's crane to lift the bell. This meant the Stena Welders divers had to attach a guide wire to the bell. This wire would then help send the Wildrakes crane hook down to the bell.

At 6:09 AM, the Stena Welder diving bell went into the water. Rescue divers Phil Kasey-Smith and Eddy Frank were inside. There were problems with communication and lights on their bell. Also, the Wildrake bell's tracking device was gone. The Wildrake crew had also forgotten they moved the bell. So, it took Kasey-Smith almost an hour to find the Wildrake bell on the seafloor. At 7:55 AM, he saw Walker and Guiel giving him a thumbs-up through a window.

Kasey-Smith spent another hour guiding a loose wire around the SALM base. The Stena Welder ship could not stay in one exact spot. This caused its bell to drag Kasey-Smith around the seabed by his umbilical. At 9:02 AM, Kasey-Smith attached the guide wire to the bell. The Wildrake started lowering its crane hook. Kasey-Smith now saw that Walker and Guiel were moving "very very frantically." The crane hook came down too far away. Kasey-Smith could not reach it. The hook was pulled up, more ropes were added, and it was sent down again. Kasey-Smith finally attached the ropes to the Wildrake bell at 10:10 AM.

The Wildrake tried to lift the bell at an angle, not straight up. They also did not check visually if the bell was clear to be lifted. During the lift, the bell got stuck against the SALM base. The lifting rope broke. The crane wire came out of the sea at 12:20 PM without the Wildrake bell. It was lost again.

When rescue diver Frank found the bell again, he saw that Walker or Guiel had tried to cut the ropes on the drop weights. This would have let the bell float to the surface. But only one of the two weights was cut free. He also saw that the trapped divers were close to dying.

Kasey-Smith and Frank were very tired. They were brought to the surface. Divers Michael Mangan and Tony Slayman took over. At 6:16 PM, Mangan reconnected the crane wire to the bell. At 7:37 PM, the bell was lifted out of the ocean. It was connected to the Wildrake's special saturation system. A doctor, Dr. Morven White, who had been put into saturation, checked Walker and Guiel. She said they were dead. Another doctor officially confirmed their deaths. Later, medical checks in Scotland showed they died from hypothermia.

What Happened After the Accident?

On August 9, 1979, government inspectors and police went onto the Wildrake. They investigated the accident. An inspector found many safety problems and signs that rules were not followed.

In May 1981, a court in Los Angeles, USA, ordered money to be paid to Walker's wife and daughter, and to Guiel's family. However, this order was never put into effect by British courts.

A special investigation into the deaths of Walker and Guiel happened in Scotland in May 1981. During this investigation, Walker's wife read from her husband's diary. He had written on August 7, 1979, "I don't even know if I'm gonna get out of here alive." The official in charge, Sheriff Douglas James Risk, gave his findings in November 1981. He said that removing the clump weight helped cause the divers' deaths. He also said that not having a bell stage showed that the diving companies cared more about speed than safety. He believed Walker and Guiel "could probably have been saved." This was if the crane lift had been stopped and checked when it got stuck.

In October 1986, the companies involved agreed to pay money to the Walker and Guiel families. No one ever admitted to doing anything wrong.

The Wildrake ship was later renamed Felinto Perry. It became a submarine rescue ship for the Brazilian Navy. In May 2000, the accident records for the Wildrake were found to be missing in London.

More Diving Accidents

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |