Statute of Anne facts for kids

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

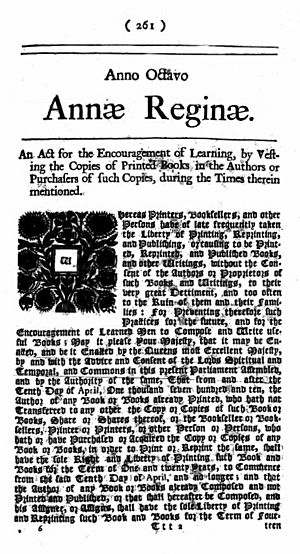

| Long title | An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 8 Ann. c. 21 or 8 Ann. c. 19 |

| Introduced by | Edward Wortley (Commons) |

| Territorial extent | England and Wales, Scotland, later Ireland |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 5 April 1710 |

| Commencement | 10 April 1710 |

| Repealed | 1 July 1842 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Copyright Act 1842 |

| Relates to | Licensing of the Press Act 1662 |

The Statute of Anne, also called the Copyright Act 1709 or Copyright Act 1710, was an important law passed in 1710 in Great Britain. It was the first law to create copyright rules that were managed by the government and courts, not by private groups.

Before this law, rules about copying books were set by the Licensing of the Press Act 1662. These rules were enforced by the Stationers' Company, a group of printers. They had the only right to print books and also had the job of censoring them. People didn't like this censorship, and authors tried to stop the Licensing Act from being renewed. In 1694, Parliament decided not to renew the Act. This ended the Stationers' Company's special power and the rules about printing.

For the next 10 years, the Stationers' Company tried to get the old system back, but Parliament said no. So, the Stationers changed their plan. They started saying that new rules would help authors, not just publishers. This new idea worked, and Parliament began to consider a new law. This law, after some changes, was approved on April 5, 1710. It became known as the Statute of Anne because it was passed during the time of Queen Anne.

The new law said that copyright would last for 14 years. Authors could also renew it for another 14 years. During this time, only the author and the printers they chose could publish the author's work. After this period, the work would become part of the public domain, meaning anyone could copy it. Even though there was a time of confusion called the "Battle of the Booksellers" when the first copyrights ended, the Statute of Anne stayed in effect until a new law, the Copyright Act 1842, replaced it.

This law is seen as a "huge turning point" in copyright history. It changed copyright from being a private right for publishers to a public right given by law. For the first time, authors, not publishers, held the copyright. The law also helped the public by making sure copies of books were given to certain libraries. The Statute of Anne influenced copyright laws in many other countries, including the United States. Even today, judges and experts still talk about it as a key example of why copyright laws are important for society.

Contents

Why the Statute of Anne Was Needed

When William Caxton brought the printing press to England in 1476, printed books became much more common and important. Early on, King Richard III saw the value of books. Later, the government started to control printing more. In 1534, a law banned importing foreign books and let the government set prices for English books.

Controlling Books and Ideas

In 1538, King Henry VIII wanted to stop certain religious ideas from spreading. He said that all authors and printers had to let the Privy Council (a group of royal advisors) read and approve books before they could be published. This was a way to control what people read and thought.

The Stationers' Company's Power

On May 4, 1557, Queen Mary I officially created the Stationers' Company. This group of publishers was given the power to print and sell books. Their leaders could enter any printing shop, destroy illegal books, and arrest anyone making them. This gave the government a way to control printing by letting the Company have a special business right.

Later, the Licensing Act 1662 kept these powers for the Company. It also added more rules about printing. Royal messengers could even search homes for illegal printing presses. This law had to be renewed every two years, and it usually was.

What Was Different About This "Copyright"

This system was not like modern "copyright." It gave a special right to copy to publishers, not authors. And it only applied to books that the Company had accepted and published. A Company member would register a book, and then they had a lasting right to print, copy, and publish it. They could sell this right or pass it on to their children.

Authors were not highly respected until the 1700s. They couldn't be members of the Stationers' Company and had no say in how their works were used.

Growing Unhappiness with the System

People really disliked the Company's special power, its censorship, and how it treated authors. John Milton wrote a famous essay, Areopagitica, criticizing the system. John Locke, a famous thinker, also wrote in 1693 that the system stopped the free sharing of ideas and gave the Company an unfair special right.

At this time, political parties were forming, and public opinion became more important. People were meeting in coffee houses and talking about ideas. This growing public unhappiness helped lead to the end of the old printing controls.

The Licensing Act Ends

In November 1694, a group in Parliament looked at laws that were about to expire. They suggested renewing the Licensing Act, but the House of Commons said no. The House of Lords tried to put it back in the bill, but the Commons refused again.

On April 18, 1695, the Lords agreed to pass the bill without renewing the Licensing Act. This decision ended the special relationship between the government and the Stationers' Company. It also ended the early form of publisher copyright and the system of censorship.

Why the Act Was Not Renewed

Many people believe that John Locke's strong arguments helped lead to this decision. Locke had been campaigning against the law, saying it was "ridiculous" that dead authors' works were kept under copyright forever. He wrote letters to Edward Clarke, a Member of Parliament, complaining about how unfair the system was to authors.

The end of the Licensing Act caused some confusion. The government no longer censored publications, and the Company's special power was gone. But it was unclear if copyright was still a legal idea without the law. Also, there was economic chaos. With no Company rules, printers in other towns started making cheaper books than those in London.

Trying to Create a New System

Not everyone was happy that the old system ended. There were 12 attempts to replace it, but they all failed at first. The first new bill was like the old Licensing Act, but it only required official approval for books about religion, history, government, or law. The Stationers' Company didn't like it because it didn't mention books as property, which would end their special right to copy. This bill did not pass.

After the Licensing Act ended, many new newspapers started. These newspapers often supported different political parties. Politicians from both sides realized how important it was to have good ways to influence voters. This made them think differently about controlling the press.

Authors Join the Call for Change

Authors, as well as the Stationers, started asking for a new system. Jonathan Swift strongly supported new rules. Daniel Defoe wrote in 1705 that without rules, "One Man Studies Seven Year... and a Pyrate Printer, Reprints his Copy immediately, and Sells it for a quarter of the Price." He said these things needed a new law.

Seeing this, the Stationers' Company changed its approach. Instead of complaining about their business, they argued that a new law would help authors. In 1706, a stationer named John How wrote that without protection for authors, "Learned men will be wholly discouraged." Using these new ideas and getting support from authors, the Company asked Parliament again in 1707 and 1709 for a copyright law.

The Statute of Anne Is Passed

Even though the first bills failed, writers like Defoe and How kept up the pressure. Defoe even wrote a draft of what the new law should say. On December 12, the Stationers' Company asked Parliament again for a law. The House of Commons allowed three Members of Parliament to create a drafting committee. On January 11, 1710, Edward Wortley introduced this bill. It was called A Bill for the Encouragement of Learning and for Securing the Property of Copies of Books to the rightful Owners thereof.

What the Bill Proposed

The bill said that anyone who imported or sold unlicensed or foreign books would be fined. To get copyright protection, every book had to be registered with the Stationers' Company. Copies of the book also had to be given to the King's Library and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The bill also said that books were property, meaning authors deserved copyright because of their hard work.

The Stationers were very excited and urged Parliament to pass the bill. It was read a second time on February 9. Changes were made, including adding more libraries to the list for book deposits. A very important change was adding a limit to how long copyright would last.

Changes and Final Approval

Other changes were made to the language of the bill. The idea that authors owned books like any other property was removed from the introduction. The bill's goal changed from "Securing the Property of Copies of Books" to "Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies." Another change allowed anyone to own and trade in copies of books, which weakened the Stationers' power.

More changes happened when the bill went to the House of Lords. It was finally sent back to the Commons on April 5. The exact goals of the new law are still debated today. Some think it tried to balance the rights of authors, publishers, and the public to spread knowledge. Others think it was meant to protect the Company's special power, or even to weaken it. Most likely, it was a mix of all these reasons. The bill passed on April 5, 1710, and is known as the Statute of Anne because it happened during Queen Anne's reign.

The Law's Details

The Statute of Anne has 11 sections. Its full name is "An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of Copies, during the Times therein mentioned."

The introduction of the law explains its purpose: to bring order to the book business. It says that printers and booksellers have been copying books without permission, which harms authors and their families. To stop this and encourage learned people to write useful books, the law was created.

Copyright and Its Rules

The law said that copyright was the right to copy. It gave authors sole control over printing and reprinting their books. This right, which used to belong to the Stationers' Company, would now automatically go to the author once the book was published. Authors could also give these rights to someone else.

To get copyright, two things had to happen:

- First, the book's publication had to be registered with the Stationers' Company. This helped prevent accidental copying.

- Second, copies of the book had to be given to the Stationers' Company, the royal library, and various universities.

The law also tried to stop books from being too expensive by limiting how much authors could charge. It also banned importing foreign books, except for old Latin and Greek classics.

How Long Copyright Lasted

Once a book was registered and copies were deposited, the author had the exclusive right to control its copying. If someone copied a book illegally, they faced serious penalties, including fines and having their copies destroyed. However, there was only a three-month time limit to bring a case to court.

The length of copyright depended on when the book was published:

- If published after April 10, 1710, copyright lasted 14 years.

- If published before that date, it lasted 21 years.

If an author was still alive when their first copyright ended, they got another 14-year term. After that, the works became part of the public domain. The Statute of Anne applied to Scotland and England, and later to Ireland when it joined the union in 1800.

What Happened After the Law Was Passed

The Law's Effects

The Statute of Anne was generally welcomed. It brought "stability to an insecure book trade" and created a "fair deal" between authors, publishers, and the public. The goal was to help public learning and make knowledge more available.

However, the rule about depositing books was not very successful. If books weren't deposited, there were fines. But the number of copies required was a big burden. Sometimes, it was cheaper for publishers to just pay the fine. Some booksellers argued that the deposit rule only applied to registered books, so they avoided registering to lower their costs.

What the Law Didn't Cover

The law also had some gaps. It didn't say how to identify authors or what exactly counted as an "authored work." It only covered "books," even though it talked about "property" in general. Also, the right it gave was mainly about "making and selling... exact reprints." It was still very similar to the old system, but now it had a time limit and was officially given to authors.

The law didn't change much for authors financially. Publishers still bought manuscripts from writers for a one-time payment, just now they also bought the copyright. The Stationers' Company still had a lot of power, so they could pressure booksellers to keep old arrangements. This meant that even works that should have been in the "public domain" were often still treated as copyrighted.

The Battle of the Booksellers

When the copyrights for older works (published before the Statute of Anne) started to expire in 1731, the Stationers' Company fought to keep their old ways. First, they asked Parliament for new laws to make copyright last longer, but this failed. Then, they went to court.

Their main argument was that copyright existed before the Statute of Anne, as a "common law" right, and that it should last forever. So, even if the law set a time limit, they believed works should still be copyrighted forever under common law. This started a 30-year fight called the "Battle of the Booksellers," beginning in 1743.

Court Cases and Decisions

Publishers first tried to get court orders to stop others from printing their works, and this worked at first. But a few years later, the law became unclear.

A major case was Millar v Taylor. Andrew Millar, a publisher, bought the rights to James Thomson's poem The Seasons in 1729. When the copyright ended, another publisher, Robert Taylor, started printing his own copies. Millar sued, arguing for lasting copyright under common law. The court agreed with Millar, saying that copyright existed "before and independent" of the Statute of Anne and should last forever. This meant authors should always get money from their work.

However, this victory for the Stationers' Company didn't last long. Another case, Donaldson v Beckett, went to the House of Lords (the highest court at the time). After talking with judges, the Lords decided that copyright was *not* forever. They ruled that the time limit set by the Statute of Anne was the longest a copyright could last for publishers and authors.

Expanding and Ending the Law

| Copyright Act 1814 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to amend the several Acts for the Encouragement of Learning, by securing the Copies and Copyright of Printed Books, to the Authors of such Books or their Assigns. |

| Citation | 54 Geo. 3. c. 156 |

Until it was replaced, most new copyright laws were based on the Statute of Anne. In 1739, a new law banned importing books that were originally from Britain but had been reprinted cheaply in other countries like Ireland. This law also removed the price limits from the Statute of Anne.

The rules about depositing books in libraries were also changed. Many booksellers found these rules unfair. In 1775, Lord North helped pass a bill that restated the deposit rules. It also gave universities lasting copyright on their own works.

More Things Get Copyrighted

The Statute of Anne only covered "books." So, new laws were needed to include other types of creative works.

- In 1734, copyright was extended to cover engravings (pictures made from carved plates).

- In 1789 and 1792, laws covered cloth designs.

- In 1814, sculptures got copyright.

- In 1833 and 1842, the performance of plays and music were covered.

The length of copyright also changed. The Copyright Act 1814 set a copyright term of 28 years, or the author's entire life if that was longer.

Calls for Stronger Copyright

Even with these changes, some people felt copyright wasn't strong enough. In 1837, Thomas Noon Talfourd tried to pass a bill to make copyright stronger. He wanted copyright to last for the author's life, plus another 60 years. He also wanted to combine all the existing laws into one clear law.

Talfourd's ideas faced opposition. Printers and publishers worried about the costs. Many in Parliament argued that his bill didn't consider the public's interest. Lord Macaulay, a famous writer and politician, helped defeat one of Talfourd's bills in 1841.

The Copyright Act 1842 finally passed, but it was not as strong as Talfourd had hoped. It extended copyright to the author's life plus seven years. As part of this new law, the Statute of Anne was officially ended.

Why the Statute of Anne Was Important

The Statute of Anne is often seen as a "historic moment" and the first law in the world to create copyright. Some experts say it was influenced by earlier laws, but it was still a "watershed event." It changed copyright from being a private right for publishers to a public right given by law. Unlike earlier laws, it did not include censorship.

It was also the first time that copyright was mainly given to the author, not the publisher. It also recognized that authors were sometimes treated unfairly by publishers. Even if authors signed away their rights, the second 14-year copyright term would automatically return to them.

Even today, the Statute of Anne is often mentioned by judges and experts. It shows the idea that copyright laws are useful for society. For example, in a court case in Australia, the judges noted that the law's title showed how important knowledge and learning were for human progress. Despite some "widely recognized flaws," the Statute of Anne became a model for copyright laws in the United Kingdom and around the world.

It influenced copyright law in the United States. The Copyright Clause in the United States Constitution and the first US copyright law, the Copyright Act of 1790, both drew ideas from the Statute of Anne. The 1790 Act also had a 14-year copyright term and rules for authors who published before 1790, just like the Statute of Anne 80 years earlier.

See also

- Licensing of the Press Act 1662

- Copyright Act 1911

- Copyright Act 1956

- Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

- Copyright law of the United Kingdom

- Common law copyright

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |