Stepan Bandera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stepan Bandera

|

|

|---|---|

|

Степа́н Банде́ра

|

|

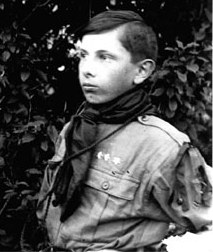

Bandera, c. 1934

|

|

| Leader of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (Banderite) | |

| In office 10 February 1940 – 15 October 1959 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established (Andriy Melnyk as leader of the OUN) |

| Succeeded by | Stepan Lenkavskyi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 January 1909 Staryi Uhryniv, Galicia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 15 October 1959 (aged 50) |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Munich Waldfriedhof |

| Citizenship |

|

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Spouse | Yaroslava Bandera |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Lviv Polytechnic |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Awards | Hero of Ukraine (annulled) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Stepan Bandera (born January 1, 1909 – died October 15, 1959) was a Ukrainian political leader. He led a part of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), called OUN-B. This group wanted Ukraine to be an independent country.

Bandera was born in a part of Austria-Hungary called Galicia. His father was a priest. From a young age, Bandera joined groups that wanted Ukraine to be free. He became a leader in the OUN. In 1934, he was arrested and sentenced to life in prison for his political actions.

He was freed from prison in 1939 when World War II started. During the war, he tried to create an independent Ukrainian state. However, the Germans arrested him again because they did not agree with his plans. He was released later in the war. After the war, he lived in West Germany. In 1959, he was killed by a Soviet agent.

Today, Bandera is a very debated person in Ukraine. Some people see him as a hero who fought for Ukraine's freedom. Others, especially in southern and eastern Ukraine, see him as a controversial figure. They point to his group's actions during World War II, which included violence against Polish and Jewish civilians. In 2010, he was given the title "Hero of Ukraine," but this award was later taken away.

Contents

Stepan Bandera's Life Story

Early Life and School

Stepan Bandera was born on January 1, 1909. His birthplace was Staryi Uhryniv, in Galicia, which was then part of Austria-Hungary. His father, Andriy Bandera, was a priest. His mother was Myroslava Głodzińska. Stepan had seven brothers and sisters.

He grew up in a family that loved their country and was very religious. He did not go to primary school because of World War I. His parents taught him at home. As a child, Bandera was small and thin. He enjoyed singing, playing music, hiking, and sports like basketball and chess.

After World War I, his home region became part of Poland. His father joined the Ukrainian army as a chaplain. He was involved in the fight for Ukrainian independence.

Bandera was inspired by a book called Independent Ukraine. After high school in 1927, he wanted to study agriculture. In 1928, he started studying at Lviv Polytechnic. However, he never finished his studies. His political activities and arrests took up too much of his time.

Early Activities for Ukraine

While in high school, Bandera joined several Ukrainian youth groups. In 1927, he joined the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO). In 1929, he became a member of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). He was inspired by Stepan Okhrymovych, a leader in the youth movement.

Bandera spent a lot of his time on secret nationalist activities. Because of this, he was arrested many times. For example, he was arrested in 1928 for celebrating a Ukrainian anniversary. He was also arrested several times between 1932 and 1933.

In the early 1930s, Polish authorities took strong actions against Ukrainians. This was in response to attacks by Ukrainian nationalists. Properties were destroyed, and many Ukrainians were arrested.

Leading the OUN

Bandera joined the OUN in 1929. He quickly became a leader. By 1930, he was in charge of spreading OUN messages in Eastern Galicia. A year later, he led propaganda for the entire OUN.

After some changes in leadership, Bandera became the main leader of the OUN in Poland in 1933. The OUN, under Bandera's orders, started carrying out attacks. These included attacks on post offices and police officers. They also campaigned against Polish government policies.

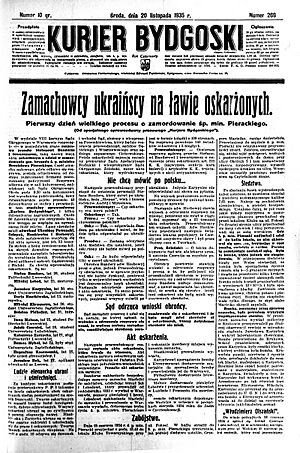

In 1934, Bandera was arrested in Lviv. He was accused of planning to kill a Polish minister. He was found guilty of terrorism and sentenced to death. However, his sentence was changed to life in prison.

After his trials, Bandera became well-known among Ukrainians in Poland. He was seen as a symbol of the fight for Ukrainian independence. Even in prison, he kept up with political news.

World War II and Ukraine

Before World War II, Ukraine was divided among Poland, the Soviet Union, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. Germany's military intelligence worked with OUN members. They wanted to weaken Polish defenses before Germany attacked. OUN leaders, including Bandera, worked with German intelligence. Their goal was to cause trouble behind enemy lines.

Bandera was freed from prison in September 1939. This happened when Germany invaded Poland. He moved to Kraków, which was under German control. There, he met with other OUN leaders. In 1940, the OUN split into two groups: OUN-B (Bandera's group) and OUN-M.

The two groups had different ideas, but both were very nationalist. Bandera's group, OUN-B, wanted Ukraine to be a single-party state. They wanted it to be free of national minorities. This group was later involved in the Holocaust.

Before Ukraine declared independence in 1941, Bandera set up "Mobile Groups." These small groups of OUN-B members traveled across Ukraine. They encouraged support for OUN-B and set up local governments. About 7,000 people joined these groups.

In spring 1941, Bandera met with German intelligence leaders. They discussed forming Ukrainian military units. The OUN received money for secret activities in the Soviet Union. German officials protected Bandera's followers.

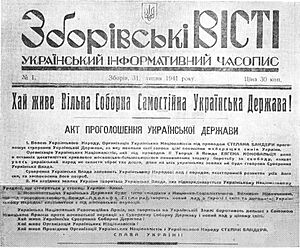

On June 30, 1941, OUN-B declared an independent Ukrainian state. This happened after German troops entered Ukraine. The declaration promised to work with Nazi Germany. However, the Germans did not approve. They asked Bandera to take back the declaration. When he refused, he was arrested by the Gestapo.

Bandera was taken to Berlin and held there. Other OUN leaders were also arrested. By late 1941, relations between Germany and OUN-B were bad. A German document even said that Bandera's group was planning a revolt.

In January 1942, Bandera was moved to a special prison in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. This prison was for important political prisoners. He was not completely cut off from the outside world. His wife visited him and helped him stay in touch with his followers.

In April 1944, German officials talked to Bandera. They wanted him to help with sabotage against the Soviet Army. Bandera was released by the Germans on September 28, 1944. They hoped he could help fight the Soviet advance.

After his release, Bandera was put under house arrest. The Germans also released about 300 other OUN members. Bandera did not like the changes happening within the OUN-B in Ukraine. He was against the group becoming more democratic.

In January 1945, Bandera was involved in forming the Ukrainian National Committee (UNK). This group aimed to fight the Soviets alongside the Germans. However, Bandera later denied any involvement with Germany after his release.

After the War

After the war, Bandera and his family moved around West Germany. They settled near Munich. There, Bandera organized the ZCh OUN, a foreign center for the OUN. He used fake identity papers to hide his past connections with the Nazis.

The ZCh OUN quickly became the largest Ukrainian organization in Germany. It had about 5,000 members. From 1948, the ZCh OUN worked with British intelligence. They exchanged information and helped transfer messengers to Ukraine. Another Ukrainian group worked with US intelligence.

US intelligence considered Bandera valuable for his knowledge of the Soviet Union. They protected him from being sent back to the Soviet Union. However, they also saw him as untrustworthy. They tried to find him in 1947 because they were worried about his activities.

The Bavarian government tried to stop Bandera's organization. They were accused of crimes like counterfeiting. However, a West German official helped protect Bandera. Bandera also offered his services to the German intelligence agency (BND).

Bandera also visited Ukrainian communities in other countries. These included Canada, Austria, and the UK.

Stepan Bandera's Death

The Soviet KGB tried many times to kidnap or kill Bandera. On October 15, 1959, Bandera died in Munich. He was buried in the Waldfriedhof cemetery in Munich. His wife and three children later moved to Canada.

Two years later, in 1961, German authorities announced that a KGB agent named Bohdan Stashynsky had killed Bandera. Stashynsky confessed to the killing. He was acting on orders from the head of the Soviet KGB. Stashynsky was found guilty and sentenced to eight years in prison. He was released after four years.

Bandera's Family

Bandera's brothers, Oleksandr and Vasyl, were arrested by the Germans. They were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. They died there in 1942.

His father, Andriy, was arrested by the Soviets in May 1941. He was executed in July. His sisters, Oksana and Marta-Maria, were arrested by the NKVD in 1941. They were sent to a labor camp in Siberia. Both were released in 1960. Marta-Maria died in Siberia in 1982. Oksana returned to Ukraine in 1989 and died in 2004. Another sister, Volodymyra, was in Soviet labor camps from 1946 to 1956. She returned to Ukraine in 1956.

Bandera's Beliefs

Historians have different views on Bandera's beliefs. Some say his worldview included strong nationalism and a belief that only war could create a Ukrainian state. They also note his dislike for democracy and communism. Some historians describe him as a fascist who wanted a one-party state in Ukraine.

Other historians argue that Bandera's main goal was Ukrainian independence. They say that other goals were less important. They also point out that the OUN's view of Nazi Germany changed over time. It shifted from initial support to rejection when the Nazis did not support Ukrainian independence.

Some experts say that calling Bandera a "Nazi" is not accurate. They describe him as a "Ukrainian ultranationalist." They argue that Ukrainian nationalism was not an exact copy of Nazism. They also note that Bandera was against too much cooperation with the Nazis. He wanted the Ukrainian movement to be independent.

Historians also discuss whether Bandera's movement had democratic elements. Some argue that it was a revolutionary movement for a stateless nation. It aimed to create a new state using all available methods.

Views on Poles

Bandera saw Russia as Ukraine's main enemy. He had little tolerance for Poles and Jews living in Ukrainian areas. In 1942, while Bandera was in a German camp, his organization was involved in mass killings of Poles. These events happened in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. It is estimated that tens of thousands of Poles were killed.

Bandera was in a German concentration camp when these killings happened. Some historians say he was not fully aware of the events. Others say he had disagreements with the OUN-B leader in Ukraine, who was a main planner of the massacres.

Views on Jews

Bandera held antisemitic views, which were common at that time. Some historians say that antisemitism was not the main focus of Ukrainian nationalism. They say the Soviet Union and Poland were seen as the main enemies. However, they also note that Ukrainian nationalists saw Jews as a "problem." This was because Jews were thought to be helping the Soviets.

Historians say that Bandera did not personally take part in the killings of Jews. However, he also never spoke out against them. He was aware of some anti-Jewish violence by his followers. For example, one of his deputies reported that they were creating a militia to "remove the Jews."

After World War II, Bandera and his supporters tried to hide their strong antisemitic views from before the war.

Bandera's Legacy

Historian David R. Marples says that Bandera's importance comes from the events that happened in his name. After the war, Soviet history painted Bandera as a fascist and a collaborator. But in Ukraine, his memory has been honored more as nationalism grew.

Attitudes in Ukraine

Bandera is still a very dividing figure in Ukraine. In western Ukraine, many people honor him. But across Ukraine, he is one of the historical figures who cause the most negative feelings.

A survey in 2013 showed that in Galicia, 53% of people had a very positive view of Bandera. In contrast, in Donbas, 57% had a very negative view. A 2021 poll showed that 32% of Ukrainians saw his actions as positive. The same number saw them as negative.

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bandera's popularity increased. A poll in April 2022 showed that 74% of Ukrainians viewed him favorably. For many Ukrainians, the most important thing about Bandera is that he fought for Ukrainian independence.

Historian Andreas Umland says that remembering history in Ukraine is complex. This is because Ukraine was terrorized by two totalitarian regimes. He also notes that Russia has used this history to spread biased stories about Bandera.

Russian Actions in Ukraine

During the 2014 crisis in Ukraine, pro-Russian groups used Bandera's name to criticize Ukrainian protesters. Russian media called Ukrainian protesters "Banderites." They said these groups were coming to harm Russians. This was used to justify Russia's actions. Russian President Vladimir Putin said he was "saving them from the new Ukrainian leaders who are the ideological heirs of Bandera."

During the 2022 invasion, Putin continued to refer to "Banderites" in his speeches. He spoke of fighting "neo-Nazis, Banderites." Russian media heavily promoted the idea of "denazification." This connected Ukrainian national identity with Nazism because of Bandera. News reports also mentioned Russian soldiers targeting people they called "Nazis" or "Banderites."

Hero of Ukraine Award

On January 22, 2010, the President of Ukraine, Viktor Yushchenko, gave Bandera the title "Hero of Ukraine." This was for "defending national ideas and battling for an independent Ukrainian state." Bandera's grandson accepted the award.

Many groups condemned this award. These included the European Parliament, Russia, Poland, and Jewish organizations. The European Parliament hoped the decision would be changed. Russia said the award was "odious" and would cause negative reactions. However, Ukrainian nationalists in western Ukraine supported the award.

After a new president, Viktor Yanukovych, took office, he said the award was illegal. This was because Bandera was never a citizen of Ukraine. A court in Donetsk ruled the award illegal in April 2010. In January 2011, the award was officially taken away. Former President Yushchenko called this a "gross error."

In 2018, the Ukrainian parliament considered giving Bandera the award again. But the proposal was rejected in 2019.

Remembering Bandera

Bandera is not a symbol of the current Ukrainian government. President Zelensky does not present him as a national hero. However, Bandera is still remembered in Ukraine.

In 2007, the city of Lviv put up a statue of Bandera. This statue caused a lot of debate about Bandera's role in Ukrainian history. Earlier statues were destroyed, so the current one is guarded. In 2007, Lviv also created an award named after Stepan Bandera for journalism.

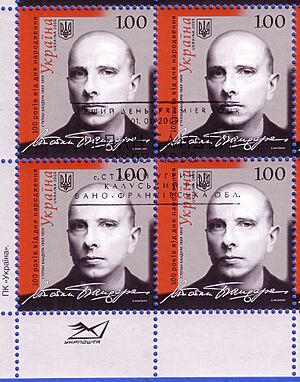

On January 1, 2009, Bandera's 100th birthday was celebrated. A postage stamp with his picture was issued. On January 1, 2014, his 105th birthday was celebrated with a torchlight procession in Kyiv. Thousands also gathered near his statue in Lviv.

There are Stepan Bandera museums in several Ukrainian towns. There is also a Stepan Bandera Museum in London. Many streets in Ukrainian cities are named after Stepan Bandera. In 2017, it was reported that 34 streets had been named after him. In 2016, Kyiv City Council voted to rename Moscow Avenue to Stepan Bandera Avenue. In 2022, a street in Dnipro was renamed to honor Bandera. The recently liberated city of Izium also renamed a street after him.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, statues of Stepan Bandera were built in many western Ukrainian cities. He was also made an honorary citizen of some cities. In 2018, the Lviv Oblast Council declared 2019 the year of Stepan Bandera. This caused protests from Israel.

In 2021, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory included Bandera in a project called Virtual Necropolis. This project remembers historical figures important to Ukraine. Two movies have been made about Bandera.

See also

In Spanish: Stepán Bandera para niños

In Spanish: Stepán Bandera para niños

- Far-right politics in Ukraine

- Our father is Bandera, Ukraine is our mother!