Sterling Iron Works facts for kids

The Sterling Iron Works was an important place where iron and steel were made a long time ago. It was owned by Peter Townsend. This company was one of the first to make steel and iron in the Thirteen Colonies (which later became the United States). It was also the very first place in New York to produce steel. The Sterling Iron Works is most famous for making the huge Hudson River Chain. This chain helped stop the British Navy from sailing up the Hudson River during the American Revolution. It also protected the very important fort at West Point. The works operated from 1761 to 1842.

Contents

Finding Iron Ore

In 1750, people found a lot of iron ore right on the surface of the ground at the south end of Sterling Mountain in Monroe, New York. The next year, Ward & Colton built a furnace that used charcoal to melt the iron. This furnace was near Sterling Lake and was the first of its kind in Warwick. They called it the Sterling Iron Works to honor General William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling. He owned the land and later became an officer in the Revolutionary army. These works made anchors, including some for the famous United States ship, USS Constitution. A second Sterling furnace was built in 1777.

More Mines Open Up

Later, more places where iron ore could be found were discovered near the Sterling mine. The Sterling mine itself covered about 30 acres (12 hectares).

The Forest of Dean mine was a very large ore bed about six miles (10 km) west-northwest of Fort Montgomery. It supplied a furnace as early as 1756 but was closed 21 years later. The ore vein there was over 30 feet (9 meters) thick and 150 feet (46 meters) wide. It produced good, strong iron.

The Long Mine was discovered in 1761 by David Jones. It belonged to the Townsend family. For the next 70-80 years, this mine supplied about 500 tons of ore each year to the Sterling Works. In total, it produced about 140,000 tons of ore. This was the only mine where they tried systematic mining during that time. They dug down 170 feet (52 meters) on a single vein that was 6 feet (1.8 meters) thick. The ore from this mine was very strong and tough. It was used to make cannons, muskets, wire, steel, and even harness buckles.

The Mountain Mine was found in 1758 by a hunter. He found it when a tree blew over and pulled up its roots, showing the ore underneath. The iron from this mine was known for being very strong and shiny. Because of this, most of it was sent to England to be coated with tin.

New York's First Metal Production

Mr. Peter Townsend bought the Sterling Iron Works before the Revolutionary War. In 1773, he made iron anchors. Then, in 1776, he produced the very first steel in New York! He first made it from pig iron (raw iron) and later from bar iron.

His son, Peter Townsend, Jr., made the first blister steel in New York in 1810. He used ore from the Long Mine on the Sterling estate. This steel was considered as good as the famous Swedish Iron from the Dannemora mine for making sharp tools.

The first cannons made in New York State were cast at Sterling in 1816 for the government. They ranged in size from 6-pounders to 32-pounders.

The Hudson River Chain

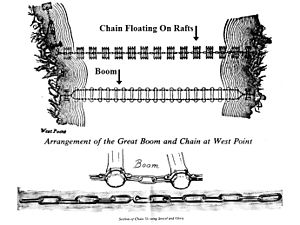

By the end of 1779, West Point was the strongest military base in America. Besides the cannons on the hills, the river itself was blocked by a huge iron chain. This chain was made from iron that came from both the Stirling and Long Mines in Orange County. The chain was made at the Stirling Iron Works, which was about 25 miles (40 km) from West Point.

Captain Thomas Machin was the main engineer for this project. He later helped with engineering during the capture of Cornwallis at Yorktown. Colonel Timothy Pickering also supervised the work.

The chain was finished in mid-April 1778. On May 1st, it was stretched across the river and secured. It weighed 186 tons and was made and delivered in just six weeks! The chain was forged at Stirling, then hauled piece by piece to New Windsor. It was put together at Captain Machin's military workshop. After that, it was floated down the Hudson River as one big piece and put into place.

This chain stayed unbroken throughout the war. Other chains at Fort Montgomery and on the lake above were broken by the British, but not this one. You can still see links from these chains, each weighing 140 pounds (64 kg), at the Military Academy at West Point.

In front of this chain was a heavy barrier made of logs, called a boom. Every winter, the chain and boom were taken out of the water. They were pulled up onto the beach to keep them safe from the moving ice. Then, they were put back in place each spring.

The chain even helped discover Benedict Arnold's plan to betray the Americans. Peter Townsend's cousin, Sally Townsend, lived in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Her brother, Robert, was a spy for General George Washington in the Culper Ring. Sally supposedly found information at her family home, which was occupied by British officers. The message from Arnold said he had weakened the chain and explained how the British Navy could break through its defenses and capture West Point. When Arnold realized he was caught, he escaped to the British side. The chain, however, remained strong throughout the war.

How the Boom in Front of the Chain Was Made

In the summer of 1777, the Ringwood Iron Works made iron for a boom. This boom was meant to be placed in front of the Fort Montgomery chain. Over 30 tons of chain links and parts were carried by ox cart from Ringwood over the Ramapo Mountains to the Hudson River. Unfortunately for the Americans, the British captured the fort and took away the chain before the boom could be properly installed.

After Fort Montgomery was captured, the iron from Ringwood was taken to West Point. It was used to make the boom placed in front of the West Point chain. This West Point chain was forged at the Sterling Iron Works and put across the river in 1778.

- Note: The large chain that is now on the front lawn of Ringwood Manor is not the famous Revolutionary War chain. It was made later and sold to Abram S. Hewitt. Even though Mr. Hewitt probably knew they were not the original, he kept the links anyway. Still, it gives a good idea of what the original huge iron barrier looked like.

- Note: In 1967, Margaret Mead and students from Ridgewood schools dug at the Long Pond Furnace site for a week. They uncovered the Revolutionary Furnace.