Stevedore operations, American Expeditionary Forces facts for kids

During World War I, the United States Army needed a way to move huge amounts of supplies through busy ports. This important job was handled by "stevedore" operations. Stevedores are workers who load and unload ships. These operations helped the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) get what they needed in France.

At first, some American stevedores in France were civilians. Later, the Army organized them into special groups called regiments. These stevedore troops were among the very first American soldiers sent to France. Three regiments and two separate battalions were sent overseas. Over time, these groups were changed into smaller battalions. They also moved from the Army Service Corps to the Transportation Corps. After the war, these battalions were closed down in France. The soldiers then returned home to the U.S.

Organizing Stevedore Workers

Stevedore operations started with about 500 civilian workers. This group was called the transport workers battalion. However, many of these workers were not experienced stevedores. They were mostly farm laborers from the American South. This meant they were not very good at handling ship cargo.

The Army's Quartermaster Corps was in charge of organizing stevedore regiments. These regiments were large groups of soldiers. One type of stevedore regiment could have nearly 2,500 soldiers. It included a main office, a supply company, two battalions, and a medical team. Each battalion had four companies, and each company had about 253 soldiers.

Recruiting Soldiers for Stevedore Work

The Army asked African American men to join as stevedores. Even married men who supported their families could join if they qualified. Many African Americans wanted to fight on the front lines. However, there were not many spots in fighting regiments for them. Stevedore jobs became a good option.

By June 1918, the Army also started looking for White men for stevedore service. They preferred men who knew how to manage African American workers. New recruits often arrived without proper uniforms. They were sometimes told the Army would give them uniforms when they got there. In December 1917, stevedores wore different uniforms or even blue work suits. They were not given weapons.

Challenges for Stevedore Recruits

The Army found that many recruits were not in good health. They had not had proper medical checks before joining. Many also had little education. Some were described as being in poor physical and mental health.

After arriving in France, many stevedores were not ready for the hard work. They had poor clothing, not enough food, and bad medical care. These problems had to be fixed before they could work well.

There were also some disagreements about how to manage the stevedores. They were first part of the Army Service Corps, which focused on labor. Later, they were moved to the Transportation Corps, which focused on moving equipment. The Transportation Corps eventually took over.

Incidents at Training Camps

The presence of African American stevedore regiments in Newport News, Virginia, led to the building of a YMCA for them. However, there were problems fitting African American stevedores into the Army. In March 1918, about 300 soldiers from a stevedore regiment had a disagreement near Newport News. This happened after an argument between a Black soldier and a White store clerk. Infantry soldiers were sent to arrest the stevedores. Some stevedores were injured, and one died.

Stevedore Units and Their Work

Stevedores were first organized into regiments. But this was not flexible enough for the different needs at ports. So, they were changed into smaller battalions. Each company had about 200 men. By spring 1918, companies were reorganized to have six officers and 250 men. This change provided enough leaders to supervise the African American soldiers.

301st Stevedore Regiment

The 301st Stevedore Regiment was formed in September 1917. It moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, in October 1917. This regiment became part of the Transportation Corps in September 1918.

In October 1918, Company A of the 301st was praised for a special achievement. They unloaded and fueled the large ship SS Leviathan in just 56 hours. This was a record!

302nd Stevedore Regiment

The 302nd Stevedore Regiment was formed in October 1917. It moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, in December 1917. This regiment also joined the Transportation Corps in September 1918.

303rd Stevedore Regiment

The 303rd Stevedore Regiment was formed in October 1917. It moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, in December 1917. Like the others, it was transferred to the Transportation Corps in September 1918.

304th Stevedore Regiment

The 304th Stevedore Regiment, also known as the 304th Training Regiment, was formed in October 1917. It had about 59 officers and over 2,700 enlisted men. This regiment was closed down in February 1918.

305th Reserve Stevedore Regiment

The 305th Reserve Stevedore Regiment had about 76 officers and 3,556 enlisted men. It was located in Newport News, Virginia.

Stevedore Battalions

- The 701st Engineer Battalion (Stevedores) was formed in September 1918. It moved to Newport News, Virginia, in October 1918. It became a Transportation Corps unit in December 1918.

- The 702nd Engineer Battalion (Stevedores) was formed in October 1918. It moved to Newport News, Virginia, in November 1918. It also became a Transportation Corps unit in December 1918.

- Many other stevedore battalions (from the 801st to the 815th) were created from the earlier stevedore regiments in September 1918.

Other Support Units

- Service Battalion Number 336 was formed in May 1918. It went to France in June 1918. It later joined the 301st Stevedore Battalion.

- Service Battalion Number 337 was also formed in May 1918. It arrived in France in June 1918. It also joined the 301st Stevedore Battalion.

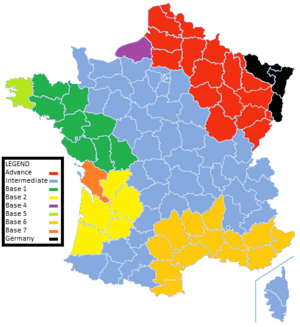

Stevedore Operations in France

Stevedores worked at American port facilities in France. These ports included Brest, St. Nazaire, Bordeaux, Havre, and Marseilles. The African American stevedores were highly praised for how quickly they unloaded troops and supplies. Their hard work was crucial for the war effort.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |