Stonegrave Minster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Holy Trinity Church, Stonegrave |

|

|---|---|

| Church of the Holy Trinity, Stonegrave | |

| Stonegrave Minster | |

The south-western aspect of the church

|

|

| 54°11′33″N 0°59′48″W / 54.19252°N 0.99663°W | |

| OS grid reference | SE655778 |

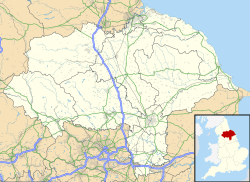

| Location | Stonegrave, North Yorkshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Stonegrave |

| Benefice | Ampleforth |

| Deanery | Northern Ryedale |

| Archdeaconry | Cleveland |

| Diocese | York |

Stonegrave Minster, also known as the Holy Trinity parish church, is a historic church in Stonegrave, North Yorkshire, England. It's famous for the special family symbols, called heraldry, found on some of its old tombs and monuments.

This church was once an "Old Minster," which means it was a very important early Christian center. It was set up before the year 757 AD. At that time, priests from places like Iona and Lindisfarne worked there. It was likely started by an early King of Northumberland.

The head of the Minster, either an abbess or abbot, also looked after churches in Coxwold and Donamuthe. Donamuthe was destroyed by the Danes in 794 AD and has now completely disappeared.

Contents

The First Church Building

The very first church building was tall, narrow, and shaped like a rectangle. Today's west wall might be a part of this original structure. You can see how old it is by looking at the tall, narrow doorway. It has a rough arch and uneven sides. This kind of door was important in early church services.

High up in the west wall, above this doorway, there's another blocked-up doorway. This used to lead from the tower to a room above the main part of the church. This room might have been a sleeping area or another small chapel. Later, the side walls of this first church had arches added to them. These arches are part of the Norman style. The original stone walls seem to have stayed in place above and between these arches. The entire east end of the church was rebuilt during the Norman period.

Ancient Stone Crosses

Inside the church, you can find pieces from four old standing crosses. There's also one cross that is almost complete, standing next to a stone block that was once its base. All these pieces were found when the church was being repaired in 1863.

- The oldest piece, with a "figure of 8 design," was carved in the 800s.

- The other pieces were made in the 900s.

- These crosses look different from those in nearby churches. They have abstract patterns and no animal shapes.

The large, complete cross shows a special carving style. It suggests it was made by people trained in the traditions of Galloway and Iona around 920 AD. On the shaft of the cross, there are three carvings:

- At the bottom, there's a figure of a Celtic Church priest. He carries a bag for his chalice, paten, and Gospels.

- Above him is a simple cross.

- At the top, a seated figure is praying with a book, in the Celtic Church style.

Next to the large cross is a rectangular stone block. This block and three other pieces used to form the base of the cross. Two of these pieces have carvings of animals.

In the 1800s, the large cross was placed on a different base. This base was a gravestone with Norse carvings. It shows an archer shooting an arrow at a deer. This carving could be a hunting scene, a story from Viking legends, or a Christian symbol.

The Norman Church

During the 1100s, Stonegrave Minster was changed to fit new church services. It also showed the importance of the de Stonegraves family. The old stone crosses were broken up and used as building blocks.

The church's foundations show that the chancel (the area around the altar) was made longer and ended in a rounded shape called an apse. This created a long view down the middle aisle to the altar, which became the main focus of worship.

Arches were added through the north wall to create a new aisle for the chapel of St Leonard. Saint Leonard is known as the patron saint of prisoners of war. This was important because one of the de Stonegraves family members was a prisoner of war in the Near East.

The north arches were built through an older wall. The arch closest to the pulpit is made of a different type of stone. The other arches have two colors of stone, like those found in Durham Cathedral. The brown stone came from near Whitby, and the lighter stone was local. The first arch's stone came from even further away. The tops of the pillars, called capitals, are also different. Some are plain, while others have carvings or are ready for carving. Where the two central arches meet, there are two interesting carved heads.

Heraldry and the Thornton Family

From the 1300s to the late 1600s, the north aisle was where the Thornton family was buried. Only two of their tombs are still there.

- The tomb closest to the tower likely belongs to William Thornton (who died in 1330). It's special because it shows a civilian figure with crossed legs.

- The other tomb is for Robert Thornton and his wife (who died in 1418). It's made of local stone. It now sits in a special space in the north wall, with a canopy made from an older Easter sepulchre. The tomb chest has figures holding shields. These shields show the family's simple coat-of-arms: three thorn sprays.

There are four main types of heraldry (family symbols) to see:

- Several large carved panels on the walls remember members of the Combers family. One of them, Thomas, was a rector (a type of priest) in the church. There's also a small brass plaque on the chancel wall.

- A large painted memorial for William Thornton (who died in 1668). It shows his complex achievement, which is a full display of his family's coat-of-arms. The main Thornton arms show three thorn trees on a silver background.

- A stone carving of a knight and a lady includes a shield, which is another Thornton symbol. Other Thornton shields can be seen, including one in a modern window in the south aisle.

Changing Styles of the Church

The Cistercian monks from nearby Rievaulx Abbey didn't like too much decoration. Because of this, the half-capital (top of a pillar) in the north arcade closest to the tower, and all the capitals in the south arcade (built a bit later, around 1165–1170), have no carvings.

The south arcade itself was also built through an early wall. The stone used for it is similar to stone found near Rievaulx. This suggests that masons from Rievaulx probably built it. The arches are simpler but harder to build. They have two full spans that make the south side of the nave (the main part of the church) feel very open. This also opens up the chapel of St Peter. The decorative band of stone between these two arches looks like those at Rievaulx. A doorway at the eastern end of this arcade might be what's left of an entrance that was used before the arches were built.

After the Reformation

During the 1500s and early 1600s, after the Reformation, many medieval carvings and church furnishings were removed by the Puritans. For example, the lead and wood from the roof of the north aisle were taken to build the roof of the rectory (the priest's house).

New furnishings were added when church ceremonies became more popular during the reign of King Charles I. One piece that survived is a light rood screen from 1637. This screen separates the altar from the worshippers but doesn't completely hide it. Alice Thornton also gave colorful altar cloths and other hangings in purple and scarlet with beautiful embroidery, but these have not survived.

Other wooden items from that time suggest there was a tall pulpit with a reading desk below it. Only the pulpit remains today. The carved panels in the chancel and the screen around the vestry (a room for the priest) might have been part of a larger structure. They may also have been part of the wood paneling that once covered the lower walls of the chancel. The carved heads of kings and queens on one of these panels were not just decorations. They showed loyalty to the king.

Another reminder of the English Civil Wars hangs on the south wall of the chancel. It's a painted memorial to William Thornton (who died in 1668). His widow could only afford this simple memorial after the difficult times and fines during the wars. The fancy coat-of-arms on the memorial is very different from the simple three-thorns symbol on the tomb chest. This painted memorial was later restored by one of the family's descendants who lives in New York.

The 1700s Church

In the 1700s, the church was mainly used for preaching and singing hymns. The altar, where Holy Communion was held only four times a year, was not very noticeable. There was a whitewashed gallery at the back for musicians. A tall pulpit stood high in the nave, above the box pews (enclosed seating areas).

Today, all that remains from this period are the memorials placed on the west wall of the nave and the north wall of the chancel. These were made by Taylor of York and show the style and lettering of that time.

Other items from the 1700s include a legal document by the south door. It lists family members and their proof of inheritance claims. This was important when possible heirs were spread out. There's also a stone behind the font (the basin for baptisms) that records a gift of money to help repair the church building.

Victorian Changes

In 1863, George Fowler Jones led a major restoration of the church. This work unfortunately destroyed most of the church's medieval (Middle Ages) interior. Some of the old gravestones with carved crosses, possibly belonging to the de Stonegrave family, now lie in the churchyard. They were moved there during the restoration.

A flat gravestone made of Purbeck marble, which once had brass letters and the head and shoulders of a person inlaid (around 1300), was placed near the south door. This was not its original spot. The marble was brought in by ship through Scarborough or Whitby. The marks left by the letters show they were made in York or Lincoln. There is also a tombstone with engraved shears (scissors) beneath the great cross.

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |