Studebaker facts for kids

Badge used in the 1950s and 1960s

|

|

|

Formerly

|

Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Automotive, manufacturing |

| Fate | Merged with Packard to form the Studebaker-Packard Corporation Merged with Wagner Electric and Worthington Corporation to form Studebaker-Worthington Some naming and production rights, along with Studebaker's South Bend plant, acquired by the Avanti Motor Company |

| Successor | Studebaker-Packard Corporation Studebaker-Worthington |

| Founded | February 1852 |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | November 1967 |

| Headquarters | 635 S. Main St., South Bend, Indiana, U.S. 41°40′07″N 86°15′18″W / 41.66861°N 86.25500°W |

|

Key people

|

|

| Products | Automobiles (originally wagons, carriages and harnesses) |

Studebaker was a famous American company. It started by making wagons and later became known for its cars. The company was based in South Bend, Indiana. It was founded in 1852 and officially became the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company in 1868.

At first, Studebaker built many types of horse-drawn vehicles. These included wagons, buggies, carriages, and even harnesses for horses.

Contents

The Studebaker Story

Early Family History

The Studebaker family came from Germany. They arrived in America in 1736. Among them was Peter Studebaker, who was a wagon-maker. This skill became very important for the family's future success.

In 1918, the company president, Albert Russel Erskine, wrote a book about Studebaker's history. He confirmed that Peter Studebaker's wagon-making trade was the start of the company's wealth.

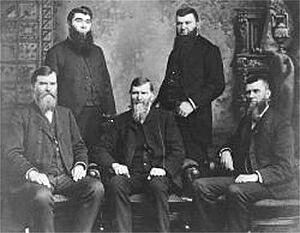

The Five Brothers

The Studebaker company was started by five brothers. Their names were Henry, Clement, John Mohler, Peter Everst, and Jacob Franklin. They also had five sisters. These brothers built on their family's long tradition of making wagons.

The First Studebaker Factory

In 1740, Peter Studebaker built his home and the first Studebaker wagon factory in Maryland. Here, he worked with steel and wood to make wagons. He also built a mill and a road called Broadfording Wagon Road. This road helped transport goods and people, making the wagon business grow.

Peter Studebaker's skills and ideas were passed down through his family. This helped the business expand across the country. They became known for making famous wagons like the Conestoga and Prairie Schooner.

From Horses to Horsepower

For a long time, Studebaker made horse-drawn wagons. John M. Studebaker believed cars would be a good addition, but he thought wagons would still be important for farmers. However, cars quickly became more popular.

By 1919, Studebaker stopped making horse-drawn vehicles. The company then focused on cars and started making trucks too. They even produced buses, fire engines, and small train parts using powerful engines.

Studebaker Cars: 1897–1966

The Beginning of Cars

In 1895, John M. Studebaker's son-in-law, Fred Fish, pushed for the company to develop a "horseless carriage." By 1897, Studebaker had an engineer working on motor vehicles.

At first, Studebaker chose to make electric cars, which ran on batteries. From 1902 to 1911, they made their own electric vehicles. They also worked with other companies to make and sell gasoline-powered cars.

The Studebaker Brand is Born

In 1911, the company officially became the Studebaker Corporation. They stopped making electric cars that year. After taking over another car company's factories, Studebaker worked hard to fix any problems with their cars. They even paid mechanics to fix issues for unhappy customers.

This effort led to Studebaker making very strong and reliable cars. From then on, all new cars made in their factories carried the Studebaker name. This showed customers that the cars were well-built.

Engineering Improvements

During World War I, Studebaker received huge orders from countries like Britain, France, and Russia. They made transport wagons, artillery parts, ambulances, and cars for the war effort.

These war orders helped Studebaker improve its engineering. They started using new engine designs and stronger materials like molybdenum steel. This led to even better cars.

First Car Testing Track

In 1926, Studebaker became the first car company in the United States to open its own outdoor testing ground. This was a special track where they could test cars in different conditions. In 1937, they even planted 5,000 pine trees there that spelled "STUDEBAKER" when seen from the air!

By 1929, Studebaker was selling many different car models. However, the Great Depression hit, causing many people to lose their jobs. This made it very hard to sell cars, even inexpensive ones.

Dealing with Tough Times

The Great Depression was a very difficult time for Studebaker. The company faced financial problems. However, with help, Studebaker managed to recover.

By 1935, the company was back on track. They introduced a new car called the Champion in 1939. This car was very popular and helped double the company's sales.

World War II Efforts

During World War II, Studebaker played an important role. They produced many Studebaker US6 trucks for the military. They also made a unique cargo and personnel carrier called the M29 Weasel. Studebaker was one of the top companies in the U.S. for wartime production.

Post-War Car Designs

After World War II, Studebaker was ready with new car designs. They used the slogan "First by far with a post-war car." Their 1947 Studebaker Starlight coupé had a unique, flat back and a wrap-around rear window. This design was very new and influenced other car makers.

Some people joked that you couldn't tell if the car was coming or going because of its unusual back design!

Leaving the Car Business

Studebaker tried to merge with another car company, Packard, in 1954. This didn't solve their money problems. The company's name was changed back to 'Studebaker Corporation' in 1962.

However, the main factory in South Bend stopped making cars on December 20, 1963. The very last Studebaker car was made in Canada on March 17, 1966. Studebaker then merged with other companies and stopped being a car manufacturer.

Studebaker's Legacy

Even though Studebaker stopped making cars, its impact is still felt today. Many classic car fans love Studebaker vehicles.

The Studebaker US6 truck, made during WWII, was used as a design for the famous GAZ-51 Soviet truck. This Soviet truck was made until 1975 and influenced many other GAZ trucks that came after it.

Also, the designers of the 1993 Dodge Ram truck said that the Studebaker E series pickup was a major inspiration for their design.

Today, you can even find "retro" audio equipment sold under the Studebaker brand name.

Products

Studebaker Car Models

- Studebaker Electric (1902–1912)

- Studebaker-Garford (1904–1911)

- Studebaker Six monobloc-engine models (1911–1918)

- Studebaker Light Four (1918–1920)

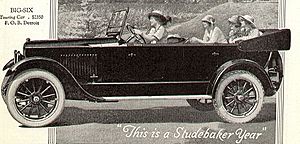

- Studebaker Big Six (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Special Six (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Light Six (includes Standard Six model) (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Commander (1927–1935, 1937–1958, 1964–1966)

- Studebaker President (1928–1942, 1955–1958)

- Dictator/Director (1927–1937)

- Studebaker Champion (1939–1958)

- Studebaker Land Cruiser (1934–1954)

- Studebaker Conestoga (1954–1955)

- Studebaker Speedster (1955)

- Studebaker Scotsman (1957–1958)

- Hawk series:

- Studebaker Golden Hawk (1956–1958)

- Studebaker Silver Hawk (1957–1959)

- Studebaker Sky Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Flight Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Power Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Hawk (1960–1961)

- Studebaker Gran Turismo Hawk (1962–1964)

- Studebaker Lark (1959–1966) (Includes the Lark-based 1964–66 Cruiser, Daytona, Commander, and Challenger)

- Studebaker Avanti (1962–1964)

- Studebaker Wagonaire (1963–1966)

Studebaker Trucks

- Studebaker GN series (1929–1930)

- Studebaker S series (1930–1934)

- Studebaker T series (1934–1936)

- Studebaker W series (1934–1936)

- Studebaker J series (1937)

- Studebaker Coupe Express (1937–1939)

- Studebaker K series (1938–1940)

- Studebaker M series (1941–1942, 1945, 1946–1948)

- Studebaker US6 (1941–1945)

- Studebaker M29 Weasel (1942–1945)

- Studebaker 2R Series (1949–1953)

- Studebaker 3R Series (1954)

- Studebaker E series (1955–1964)

- Studebaker Transtar (1956–1958, 1960–1964)

- Studebaker Champ (1960–1964)

- Studebaker Zip Van (1964)

- M35 2-1/2 ton cargo truck (1950s through 1964)

Studebaker Car Styles

- Studebaker Starlight (1947–1955, 1958)

- Studebaker Starliner

- Coupe Express

Other Car Brands Connected to Studebaker

- Tincher: An early luxury car builder Studebaker invested in, 1903–1909

- Studebaker-Garford: Cars with Studebaker bodies, 1904–1911

- E-M-F: Car maker that sold cars through Studebaker dealers, 1909–1912

- Erskine: A car brand made by Studebaker, 1926–1930

- Pierce-Arrow: Owned by Studebaker from 1928–1934

- Rockne: A car brand made by Studebaker, 1932–1933

- Packard: Merged with Studebaker in 1954

- Mercedes-Benz: Sold through Studebaker dealers, 1958–1966

Advertisements and Logos

-

1924 illuminated tiled display for Big Six touring car in Seville

See also

In Spanish: Studebaker para niños

In Spanish: Studebaker para niños

- Automotive industry

- Charles Brady King

- List of defunct United States automobile manufacturers

- South Bend Watch Company (maker of Studebaker watches)

- Studebaker Canada Ltd.

- Studebaker National Museum

- Story Monument

- The Three Musketeers (Studebaker engineers)

- Turning Wheels magazine

- Tippecanoe Place

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |