Sunningdale Agreement facts for kids

The Sunningdale Agreement was a plan to bring peace and shared government to Northern Ireland in the 1970s. It aimed to create a special government called the Northern Ireland Executive where different groups would work together. The agreement also planned for a Council of Ireland to help Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland cooperate.

The agreement was signed on 9 December 1973, in Sunningdale, Berkshire, England. However, many Unionists (people who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom) were against it. Their strong opposition, along with violence and a big strike, led to the agreement failing in May 1974.

Contents

Setting Up the Northern Ireland Assembly

In March 1973, the British government suggested creating a new Northern Ireland Assembly. This assembly would have 78 members chosen by a fair voting system called proportional representation. This system helps smaller parties get seats.

The British government planned to keep control over important areas like law, order, and money. The new assembly was meant to replace the old Stormont Parliament. People hoped this new assembly would not be controlled by just one party, like the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), and would be fair to all groups, including Nationalists.

Elections for this new assembly happened on 28 June 1973. Parties that supported the agreement, like the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), the UUP, and the Alliance Party, won most of the seats. They had 52 seats compared to 26 for those against the agreement. However, a large number of people within the Ulster Unionist Party still did not support the plan.

Forming a Power-Sharing Government

After the assembly elections, talks began to form a "power-sharing executive." This meant that different political parties, including Unionists and Nationalists, would share power in the government. The main topics discussed were internment (holding people without trial), policing, and the idea of a Council of Ireland.

On 21 November 1973, the parties agreed to form a government where they would work together. This was different from later agreements, which used a specific formula to choose ministers.

Important members of this new government included:

- Brian Faulkner, a Unionist, as the chief executive (like a prime minister).

- Gerry Fitt, leader of the SDLP, as the deputy chief executive.

- John Hume, another SDLP leader and future Nobel Prize winner, as Minister for Commerce.

- Oliver Napier, leader of the Alliance Party, as Legal Minister.

This new power-sharing government started its work on 1 January 1974. The UUP was very divided about joining this government. A vote showed that 132 members supported it, while 105 were against it.

| Role | Minister | Party | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chief Executive | Brian Faulkner | UUP | Unionist |

| Deputy Chief Executive | Gerry Fitt | SDLP | Nationalist |

| Minister of Agriculture | Leslie Morrell | UUP | Unionist |

| Minister of Commerce | John Hume | SDLP | Nationalist |

| Minister of Education | Basil McIvor | UUP | Unionist |

| Minister of the Environment | Roy Bradford | UUP | Unionist |

| Minister of Finance | Herbert Kirk | UUP | Unionist |

| Minister of Health and Social Services | Paddy Devlin | SDLP | Nationalist |

| Minister of Housing, Local Government and Planning | Austin Currie | SDLP | Nationalist |

| Minister of Information | John Baxter | UUP | Unionist |

| Legal Minister and Head of the Office of Law Reform | Oliver Napier | Alliance | Non-sectarian |

The Council of Ireland Plan

The idea of a Council of Ireland had been around since 1920, but it had never been put into action. Many Unionists did not like the idea of the Republic of Ireland having any say in Northern Ireland's affairs.

In 1973, after the power-sharing government was agreed upon, talks focused on setting up the Council of Ireland. These talks happened from 6 to 9 December in Sunningdale. The British Prime Minister Edward Heath, the Irish leader (Taoiseach) Liam Cosgrave, and the three parties supporting the agreement were all involved.

They agreed on a Council of Ireland with two parts:

- The Council of Ministers would have seven members from Northern Ireland's power-sharing government and seven from the Irish Government. Its job was to make decisions and help with cooperation.

- The Consultative Assembly would have 30 members from the Dáil Éireann (Irish Parliament) and 30 from the Northern Ireland Assembly. Its role was to give advice and review things.

On 9 December, the agreement was officially announced. It became known as the "Sunningdale Agreement."

Reactions to the Agreement

It was decided that the Council of Ireland's main tasks would be limited to things like tourism, protecting nature, and animal health. However, this did not calm the fears of Unionists. They worried that any influence from the Republic of Ireland would be a step towards a united Ireland. Their fears grew when an SDLP politician, Hugh Logue, publicly said the Council of Ireland would "trundle unionists into a united Ireland."

The day after the agreement was announced, on 10 December, loyalist paramilitary groups formed the Ulster Army Council. This group, which included the Ulster Defence Association and the Ulster Volunteer Force, strongly opposed the agreement.

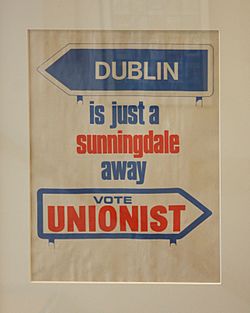

In January 1974, the Ulster Unionist Party voted against continuing to be part of the assembly. Brian Faulkner then resigned as leader and was replaced by Harry West, who was against Sunningdale. The next month, a general election took place. Anti-agreement Unionists formed a group called the United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC). They put forward one candidate in each area to oppose the Sunningdale Agreement.

The parties that supported Sunningdale, like the SDLP and Alliance, were not united and ran candidates against each other. The UUUC won 11 out of 12 seats in Northern Ireland. They said this showed that people did not want the Sunningdale Assembly and government. They then tried to bring them down.

In March 1974, some Unionists who had supported the agreement changed their minds. They demanded that the Republic of Ireland first remove Articles 2 and 3 from its constitution. These articles claimed Northern Ireland as part of the Republic. (These articles were not changed until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998).

How the Agreement Collapsed

After a vote in the Northern Ireland Assembly failed to stop power-sharing, a loyalist group called the Ulster Workers' Council called for a general strike starting on 15 May 1974.

For two weeks, there were roadblocks, shortages, riots, and threats. On 28 May 1974, Brian Faulkner resigned as chief executive, and the Sunningdale Agreement collapsed.

The strike worked because the British government did not want to use force to stop the disruption of important services. The most damaging part of the strike was its effect on electricity. The Ballylumford power station provided most of Northern Ireland's electricity. The workers there were mostly Protestant and controlled by the Ulster Workers' Council.

In later strikes, security forces were ready to act immediately. This meant that roadblocks, which were key to the success of the 1974 strike, were quickly removed.

Legacy of Sunningdale

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) of 1998, which set up the current way Northern Ireland is governed, is quite similar to the Sunningdale Agreement. SDLP politician Séamus Mallon, who was involved in the 1998 talks, famously called the GFA "Sunningdale for slow learners."

However, some experts say there are important differences between the two agreements. They point out that the situations around the talks and how the agreements were put into action were very different. For example, in 1973, some republicans believed that Britain would eventually leave Northern Ireland, but this was not the case in 1998.

See also

- Unionism in Ireland (Sunningdale Agreement and the Ulster Workers' Strike)

- Anglo-Irish Agreement

- Downing Street Declaration

- Good Friday Agreement

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |