Tetragonula hockingsi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tetragonula hockingsi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Side view - female worker | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Tribe: | Meliponini |

| Genus: | Tetragonula |

| Species: |

T. hockingsi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tetragonula hockingsi Cockerell, 1929

|

|

|

|

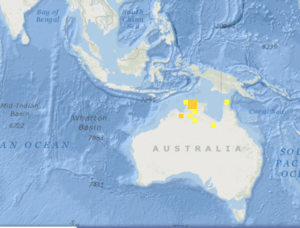

| Where T. hockingsi lives | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Tetragonula hockingsi is a small stingless bee that lives in Australia. It was first described by Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell in 1929. You can mostly find these bees in the Northern Territory and northern Queensland. Their colonies can grow very large, with up to 10,000 worker bees and one queen bee. Sometimes, Tetragonula hockingsi workers have big fights with other Tetragonula bee species. They risk their lives to protect important resources like food and their home.

Contents

About T. hockingsi

Tetragonula hockingsi is a type of stingless bee. This means it belongs to a group of bees called Meliponini, which has about 500 different species. T. hockingsi is part of the Tetragonula family. This bee species is named after Harold J. Hockings, who wrote many important notes about Australia's stingless bees back in 1884.

Changing Names

Tetragonula hockingsi used to be called Trigona hockingsi. However, its name was changed recently, following the work of Charles Duncan Michener. In 1961, a bee expert from Brazil, Professor J.S. Moure, suggested the name Tetragonula. He wanted to make the bee classification system better by splitting the very large Trigona group into smaller sub-groups. This new classification divides Trigona into 9 smaller groups. The Tetragonula group includes about 30 other stingless bee species. These bees are found in places like Australia, Indonesia, New Guinea, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, and the Solomon Islands.

What Does It Look Like?

T. hockingsi bees are easy to spot because they are completely black. The sides of their body (called the thorax) are covered with many fine, short hairs. This helps tell them apart from other species like T. clypearis and T. sapiens. The only main difference between T. hockingsi and T. carbonaria is that T. hockingsi is a bit bigger.

How to Tell Them Apart

A female worker bee is usually about 4.1 to 4.5 millimeters long. Her wings are about 4.4 to 4.7 millimeters long, including a small part called the tegula. The sides of her body are covered with fine hairs.

A male drone bee is typically 4.0 to 4.4 millimeters long. His wings are about 4.5 to 4.7 millimeters long. The male's back legs (hind tibia) are wide and flat. The last part of his body (last tergum) is rounded at the end.

Where Do They Live?

Bees from the Trigona group are commonly found in warm, tropical areas. T. hockingsi bees like to build their nests inside hollow dead trees or logs. You can find T. hockingsi bees all over northern Australia, especially in parts of the Northern Territory and along the north coast of Queensland.

How They Build Their Homes

T. hockingsi bees build their brood cells (where the young bees grow) in small, uneven horizontal layers. This is different from T. carbonaria, which builds its larval cells in a spiral shape. Also, T. hockingsi nests do not have a long, sticking-out entrance tunnel. The combs inside the nest are very important. They are where the worker bees live, where food is stored, and where the young bees are raised. The wax of the combs also helps spread special scents (pheromones) and creates a unique smell for the nest. T. hockingsi bees use very little, or no, resin and wax to line the entrance holes of their nests.

Life in the Colony

All stingless bees in the Meliponini group build special cells in a brood chamber inside their nest. Unlike other bee groups, they do not reuse these cells. Instead, they constantly build new ones. The brood chamber is surrounded by many layers of a protective cover called the involucrum. T. hockingsi builds its brood combs during a process called Provisioning and Ovipositioning (POP). First, worker bees build a new brood cell and fill it with liquid food. Next, the queen bee lays an egg on top of this food in the cell. Finally, the worker bees close and seal the brood cell. This completes the POP.

Tetragonula hockingsi builds its brood cells in an older, more basic way. They create loose groups of cells with lots of space between them. The cells are built randomly within horizontal layers, which are flat areas of cell clusters. These brood layers are held up by pillars, which are vertical wax structures. These pillars also act as connectors, allowing bees to move between the different layers. Only a small number of worker bees are involved in building these cells. The average size of a brood cell for T. hockingsi is about 3.35 millimeters wide and 4.0 millimeters tall.

Bee Behavior

How They Find Food

Like other stingless bees, individual worker bees make choices that affect how the whole colony finds food. These choices depend on the environment, information from the colony, and the bee's own instincts. T. hockingsi colonies have clear daily patterns for finding food. These patterns are influenced by things like how much food is available, sunlight, temperature, and wind speed. These bees collect the most pollen in the morning. However, they collect resin (a sticky plant material) steadily throughout the day, without any big peaks of activity.

Bee Battles

Fighting Other Bees

Small fighting groups, called skirmishes, are common among Tetragonula bees. Sometimes, these small fights can turn into much bigger battles, leading to the deaths of hundreds of bees. When Tetragonula colonies fight, the winning colony can even take over the defeated hive. This means they get the territory, resources, and nest of the other colony.

Often, T. hockingsi colonies will invade nearby T. carbonaria hives. A common tactic is for T. hockingsi workers to kick out the young adult T. carbonaria bees from the hive. This makes the fight shorter and less costly, meaning fewer bees die. The T. hockingsi colony still takes control of the hive entrance. When they win, they gain valuable resources like pollen, propolis (bee glue), and honey. This big reward might explain why workers are willing to risk their lives to attack or defend a nest.

Why Bees Fight to the Death

In these fighting swarms between Tetragonula colonies, the attacking bees face a huge risk of dying. Fighting to the death is not common in nature. It's believed that this behavior evolved because the value of the resources (like food and a home) is greater than the value of an individual worker bee's life. The benefits for each bee in the attacking hive (gaining resources and making the colony safer) must be more important than the risk of losing many workers. Scientists think that these fighting swarms between Tetragonula colonies developed as a way to survive and thrive. Taking over another nest might have started from behaviors like defending territory, raiding nests, finding new nest sites, or swarming to reproduce.

Bees and People

Beekeeping

T. hockingsi is a great bee for beekeeping, and many beekeepers like to keep one colony. It's common to keep these stingless bees in a log nest, rather than trying to move the colony. Keeping stingless bees in Australia is a fairly new practice. As of 2013, there were more than 600 commercial hives in Australia that contained stingless bees from the Tetragonula group.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |