Thomas Savery facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Savery

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | c. 1650 |

| Died | 1715 London, England

|

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

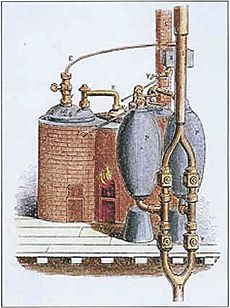

Thomas Savery (around 1650 – May 15, 1715) was an English inventor and engineer. He created the first steam-powered machine used for business. This machine was a steam pump, often called the "Savery engine." His steam pump was a new way to move water. It helped drain water from mines and made it easier to supply water to towns.

Contents

Thomas Savery's Early Life and Work

Thomas Savery was born in a large house called Shilstone, near Modbury, in Devon, England. He became a military engineer, reaching the rank of captain by 1702. In his free time, he liked to experiment with machines.

In 1696, he received a patent for a machine that could polish glass or marble. He also patented a device for "rowing ships with greater ease." This involved paddle-wheels moved by a capstan. However, the navy did not approve this invention.

Savery also worked for a group that supplied medicines to the Navy. This job took him to Dartmouth, Devon. This is likely how he met Thomas Newcomen, another famous inventor.

How Savery's Steam Pump Worked

On July 2, 1698, Savery patented his steam-powered pump. He called it "A new invention for raising of water by the force of fire." He said it would be very useful for draining water from mines and supplying water to towns. People often called it the "Savery engine." He showed his invention to the Royal Society in 1699.

In 1702, Savery wrote a book called The Miner's Friend. In it, he explained how his machine worked. He claimed it could pump water out of mines.

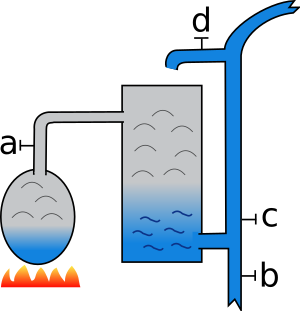

Savery's pump was special because it didn't have a piston. It only had taps that moved. Here's how it worked:

- First, steam was made in a boiler.

- This steam went into a working vessel. It pushed air and water out through a pipe.

- Once the vessel was full of steam, the tap to the boiler was closed. Sometimes, the outside of the vessel was cooled.

- Cooling the vessel made the steam inside turn back into water (condense). This created a partial vacuum (a space with very little air).

- The air pressure from outside then pushed water up the pipe into the vessel until it was full.

- Next, the tap below the vessel was closed. The tap to the up-pipe was opened. More steam from the boiler was let in.

- As the steam pressure grew, it pushed the water from the vessel up the up-pipe to the top of the mine.

However, Savery's pump had some challenges:

- Wasted Heat: Each time water entered the vessel, a lot of heat was lost warming up the water being pumped.

- High Pressure: The pump needed very high-pressure steam to push water up. The parts of the pump, especially the soldered joints, often broke under this high pressure. They needed frequent repairs.

- Deep Mines: To clear water from a deep mine, many pumps would be needed, placed one above the other.

- Limited Suction: Water was only pulled into the pump by air pressure. This meant the pump had to be no more than about 30 feet (9 meters) above the water level. So, it had to be placed deep inside the dark mines.

The Fire Engine Act

Savery's first patent in 1698 protected his invention for 14 years. The next year, 1699, a special law was passed. This law extended his patent protection for another 21 years. This law was called the "Fire Engine Act." It meant that Savery's patent covered all pumps that used fire (steam) to raise water.

Because of Savery's broad patent, Thomas Newcomen had to work with him. By 1712, Newcomen had developed a better steam engine. This new engine was sold under Savery's patent. Newcomen's engine used only air pressure to work, which was safer than high-pressure steam. It also used a piston, an idea from Denis Papin in 1690. This made it the first steam engine that could lift water from very deep mines.

After Savery died in 1715, his patent rights went to a company. This company, called The Proprietors of the Invention for Raising Water by Fire, gave permission to others to build and use Newcomen engines. They charged a lot of money for these rights, sometimes as much as £420 per year. The Fire Engine Act lasted until 1733.

Where Savery's Steam Pump Was Used

In March 1702, a newspaper announced that Savery's pumps were ready. People could see them at his workshop in London.

One of his pumps was set up at York Buildings in London. It was said to produce steam "eight or ten times stronger than common air." But this high pressure often broke the pump's joints.

Another pump was built to help control the water supply at Hampton Court. One at Campden House in Kensington worked for 18 years.

Some Savery pumps were tried in mines. One attempt was made to clear water from a flooded area called Broad Waters in Wednesbury. But the pump could not handle the large amount of water. The steam pressure was so great that it "rent the whole machine to pieces." This pump was put aside, and the idea of using it there was given up.

Savery's Pump vs. Newcomen's Engine

Savery's steam pump was cheaper to build than the Newcomen steam engine. A 2 to 4 horsepower Savery pump cost about 150–200 GBP. It also came in smaller sizes, even down to one horsepower. Newcomen's engines were much larger and more expensive. Savery-type pumps continued to be made until the late 1700s.

Later Inventions Inspired by Savery

Several later pumping systems were based on Savery's pump. For example, the twin-chamber pulsometer steam pump was a successful improvement on his design.

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Savery para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Savery para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |