Veronese Easter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Veronese Easters |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French campaign of 1797 in Italy and the Fall of the Republic of Venice | |||||||

Verona's Guardia Nobile (in blue and yellow and tricornes) and Schiavoni troops (in red jackets and black fezs,) during a re-enactment of the Pasque Veronesi. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Francesco Battaia | ||||||

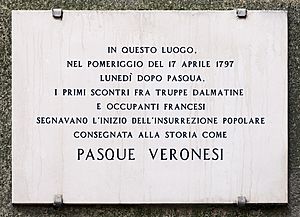

The Veronese Easter (also known as Pasque Veronesi) was a big rebellion in 1797. It happened during the Italian campaign when France was fighting many European countries. People in Verona, a city in Italy, and nearby areas rose up against the French army. The French forces were led by Antoine Balland. This happened while Napoleon Bonaparte, the top French commander, was fighting in Austria.

The revolt got its name because it was similar to the Sicilian Vespers, another anti-French uprising from the 1200s. The French soldiers were acting like occupiers. They took things from Verona's citizens and tried to change the city's government. The rebellion started on April 17, 1797, which was the second day of Easter. The angry people quickly defeated over a thousand French soldiers. They forced them into the city's forts, which the crowd then captured. The uprising ended on April 25, 1797. About 15,000 French soldiers surrounded and took over Verona. The city then had to pay a huge fine and give up many valuable items, including artwork.

Contents

What Was the Veronese Easter?

The Veronese Easter was the most important part of a larger movement. Many people across Italy fought against the French and their ideas from 1796 to 1814. Other famous uprisings included the `Armata della Santa Fede` in Naples and the `Viva Maria` group in Tuscany. These revolts were mainly against French rule. They also opposed the French political ideas, which were very different from what most Italians believed at the time. Many people joined these revolts. Some reports say at least 280,000 rebels fought, and 70,000 people died.

Why Did the Revolt Happen?

Even in 1796, Napoleon wanted to take over the rich region of Lombardy, which belonged to Venice. French troops arrived in cities like Brescia and Verona by the end of the year. People first welcomed them, thinking they would not stay long. But these cities were officially under Venetian control. This set the stage for problems later on.

French troops came to Verona on June 1, 1796. They took over military bases and stayed in other buildings. This happened even though Venice had said it was neutral in the war.

Tensions Grow in Verona

From the start, people and Venetian officials found it hard to get along with the French. The French soldiers acted more like occupiers than guests. For example, in Bergamo, a city near Verona, the French general asked to keep troops there. The city had to agree because it was neutral and could not fight back.

Napoleon had a secret plan. He wanted to change the region's government to be more like France's. This would create a new republic allied with France. When Venetian officials found out, they were worried. They tried to stop the French without using force, but it was too late. Bergamo became the first city in the Veneto region to be taken from Venice's control.

The French then moved to Brescia. They wanted local supporters to take over the government there. On March 16, French and local supporters marched to Brescia. The city's leader wanted to fight, but he was told not to use force. Two days later, 200 men entered Brescia. They easily took control with the help of local supporters. They then chased away the Venetian official who had fled to Verona.

Verona Prepares to Fight

On March 22, the Venetian official, Francesco Battaia, arrived in Verona. He met with other military leaders. They discussed taking back the lost areas. Some leaders, like conte Emilei, argued that they needed to fight. They said Verona's citizens were ready to fight against the French. Battaia eventually agreed to defend Verona's borders. This was meant to stop local French supporters, but also to prevent Napoleon's army from returning.

They quickly prepared for defense. Leaders were placed in charge of different defense lines around Verona. Meanwhile, a man named Augusto Verità, who had good relations with the French, tried to get them to stay neutral. He wrote to the French commander in Verona, General Antoine Balland. He asked for permission to defend Verona's borders. Balland agreed, and Napoleon also said French troops would not get involved. This made the people of Verona very excited to defend their land.

Many volunteers joined the defense, especially from the Valpolicella area. On March 23, news came that 500 French supporters were marching from Brescia. Officials and troops quickly took their positions.

Around the same time, people in Salò rose up. They were encouraged by Battaia, who promised them supplies. They raised the flag of Venice and forced the French supporters to flee. Other nearby towns also revolted. French and Polish soldiers gathered in Brescia to fight the rebels. They met near Salò, but the rebels lacked ammunition and had to retreat. In a second fight, the people of Salò won. They killed 66 enemy soldiers and captured several leaders.

However, a Venetian attack on Desenzano failed. News came that the French were attacking rebels in other areas. This showed that the French army still had the upper hand. A Venetian commander, Maffei, wanted to march on Brescia. But Battaia stopped him, fearing it would give France a reason to declare war on Venice.

General Charles Edward Kilmaine gathered 7,000 men in Milan and marched towards Brescia. He attacked villages along the way. Meanwhile, General Landrieux threatened Maffei with bombing Verona if he did not leave. After two small fights, Maffei decided to retreat towards Verona.

The Final Days Before the Revolt

Napoleon believed that Venice's last forces were in Verona. Even though Venice had been taking action, it still said it was neutral. Napoleon sent a spy to Verona. This spy met with about 300 French supporters to plan a secret uprising. But the police found out. On April 11, patrols arrested many of them. The spy and other leaders escaped to the French-held forts in Verona. The Venetian officials protested, but the French commander, Balland, just fortified the forts.

News also came that the French had stopped other rebellions. On April 15, the fort of Peschiera del Garda, in Verona's territory, officially became French. French troops were also moving towards other towns.

French troops were welcomed into Castelnuovo because of the neutrality. But when some Venetian soldiers left their weapons outside a church, the French took them. This was another break of neutrality. After ten months of French occupation, the situation in Verona was very tense. French soldiers often took things from citizens and plotted with local French supporters to change the government.

The Uprising Begins: April 17

During the night of April 16-17, 1797, a fake message was put up in Verona's streets. It seemed to be from Francesco Battaia, telling Verona to rebel. But it was actually a trick by the French to have an excuse to take over the city. The message was easily proven fake. It had been published before, and Battaia was not even in Verona. Venetian officials took down the messages and put up new ones, telling people to stay calm. But the revolt had already started.

Around 2 PM, French soldiers tried to provoke the crowd. They arrested a Venetian soldier. Then a fight broke out in a tavern. The French soldier lost and ran back to his patrol. This is when people started to arm themselves. A rifle shot made the French soldiers run away. More fights broke out, and people attacked guards at bridges. French commanders sent 600 men to Piazza Bra to watch.

The people were calming down when, around 5 PM, General Balland ordered cannons to fire from the French forts. Many shots landed in Piazza dei Signori. The French did this to have a reason to officially occupy the town. Verona's citizens were going into church at that moment and became very angry.

The first big fight happened in Piazza d'Armi. French troops were near the hospital, and Venetian soldiers were nearby. When the French cannons fired, the French troops ran towards Castelvecchio. The Venetian troops were confused, as they had been told for months to stay neutral. Meanwhile, people in nearby buildings started shooting, injuring French soldiers.

People attacked French troops hiding in buildings. Many soldiers were killed or captured. The French continued to bomb the city from their forts. Francesco Emilei, a Venetian commander, heard about the revolt and quickly marched back to Verona with his troops. The French had doubled their guards at the city gates, but the people easily captured them. Emilei entered the city with 2,500 volunteers and two cannons.

Armed with rifles, pistols, and even pitchforks, the townspeople rushed through the streets. They killed, wounded, and captured many Frenchmen. One of the first things they did was free Austrian prisoners to join the rebels.

In the late afternoon, Emilei decided to go to Venice to ask for help. But the Venetian government representatives in Verona tried to make a deal with the French. They stopped the church bells and raised a white flag. Balland paused the bombing. Negotiations began, but Balland wanted to stall for time so French reinforcements could arrive.

The talks failed. The Venetian governors then tried to calm the people, but it was useless. Fearing what would happen, the governors decided to leave for Vicenza. Before they left, they told their troops not to fight. So, on April 18, the governors left for Venice to ask for help from the Senate. The people continued to attack any buildings where French soldiers were hiding. The streets echoed with shouts of "Viva San Marco!"

Days of Battle: April 18-19

On April 18, with the governors gone, Emilei prepared to go to Venice. In Verona, military leaders tried to organize the army and the people. The French cannons in the forts started firing again as soon as the truce ended. French attacks from the forts were quickly pushed back.

News of the governors' flight angered the people. They kept fighting without much coordination. Many peasants and mountain people arrived from the countryside, some armed. The French forts continued to bombard the city. Some citizens managed to move cannons to a higher hill, San Leonardo. From there, they could easily fire down on the French forts.

The main goal became capturing Castel Vecchio. People moved cannons to attack it. Austrian soldiers, who were more skilled, later took over the cannons. Meanwhile, conte Augusto Verità arrived with 200 Austrian prisoners. The French in Castel Vecchio put a cannon on top of a clock tower and started firing. But Verità fired back, hitting the tower and forcing the French to leave it.

Many peasant volunteers arrived from the countryside, armed with simple tools. They were determined to fight for their homeland. Peasants attacked a church near Rivoli Veronese, and mountain people attacked forts from the north. Verona's borders were guarded and calm for the moment.

An Austrian colonel, Adam Adalbert von Neipperg, arrived in the city. He told Balland about a peace treaty Napoleon had made between France and Austria. The people rejoiced, thinking he was bringing help. But this meant the rebels lost the support of Austrian troops. Verona was bombed from the forts, and its people continued to fight.

On April 19, Venetian forces were defeated at Legnago and Bardolino. Only Maffei's troops were outside Verona. He decided to retreat to avoid being cut off by the French. Emilei returned from Venice without the hoped-for help. The two Venetian representatives tried to negotiate again with Balland. The general said he would leave if the people disarmed, but he no longer trusted anyone.

The battle continued, especially at Castel Vecchio. The cannons were now in the hands of inexperienced citizens, so they did not do much damage. The forts kept bombing the city, causing fires and damage. During one French attack from Castel Vecchio, they set fire to two palaces. But on their way back, almost all the French soldiers were killed by the rebels. Near a French hospital, armed peasants heard shots. They broke in and killed the six French soldiers they found inside.

In the afternoon, the Austrian colonel and his soldiers left Verona. He warned the people that if they resisted while the truce was still on, he would return to help them. Meanwhile, French scouting parties approached the city gates but were driven back by cannon fire from the walls.

The Final Stand: April 22-23

On the morning of April 22, the French tried to force their way into the city again but were stopped by gunfire from the citizens on the walls. The French soldiers inside Castel Vecchio were in a bad situation, and many escaped. There was also an attempt to retake the Hill of Saint Leonardo.

The rebels were running out of gunpowder and ammunition. Food was also scarce because so many volunteers and soldiers had come into the city. The Venetian government sent a letter telling the city to surrender. After a meeting, the city leaders decided they could not get more help. They began preparing to surrender. Military leaders went into the streets and told everyone to stop fighting. Venetian officials tried to calm the people. Their advice worked, and the people were convinced to stop fighting. The battle, which had lasted from April 17 to April 23, finally ended. The loud sounds of battle were replaced by a deep silence.

The people of Verona had managed to fight off French attacks and endure the bombing. But they could not resist a siege by 15,000 soldiers. So, on April 23, they decided to surrender. They sent a message to Balland asking for a 24-hour truce. The commander agreed to a break until noon the next day.

Out of the three thousand French soldiers in Verona, five hundred were killed, and about a thousand were wounded. Five hundred soldiers and nineteen hundred of their family members were captured by the rebels.

The End of the Revolt

The revolt ended with the surrender of Verona on April 23, 1797. The city was then fully occupied by the French army.

What Happened Next?

After the French victory, Verona was forced to pay a huge fine. The city also had to give up many valuable items, including precious artwork. This event was a major step towards the Fall of the Republic of Venice, which happened shortly after. The Veronese Easter showed the strong desire of the Italian people to resist French control during this period.

See also

- Devotion of Verona to Venezia

- Domini di Terraferma

Sources

- "Pâques véronaises", in Charles Mullié, Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 à 1850, 1852

- 211° Anniversario delle Pasquale Verona

- E. Bevilacqua. Le Pasque Veronesi. Verona, Remigio Cabianca Libraio, 1897.

- G. Bacigalupo. Le Pasque Veronesi: sonetti. Bologna, Libr. Beltrami, 1914.

- E. Fancelli. L'ussero di Napoleone o le pasque veronesi. Firenze, G. Nerbini, 1931.

- R. Fasanari. Le Pasque veronesi in una relazione inedita. Verona, Linotipia Veronese, 1951.

- A. Zorzi. La Repubblica del Leone. Storia di Venezia. Milano, Rusconi, 1979.

- R. M. Frigo. Le Pasque veronesi nella relazione, inedita, di un generale napoleonico. Verona, Fiorini, 1980.

- I. Menin. Breve storico compendio della Guerra d'Italia dell'anno 1796–1797. Verona, Biblioteca civica, 1997.

- F. Bonafini. Verona 1797: il furore di una città. Verona, Morelli, 1997.

- E. Santi. Le Pasque Veronesi. Ronco all'Adige, Comune di Ronco all'Adige, 1997.

- F. M. Agnoli. Le Pasque veronesi: quando Verona insorse contro Napoleone. Rimini, Il Cerchio, 1998. ISBN: 88-86583-47-8.

- F. M. Agnoli. I processi delle Pasque veronesi: gli insorti veronesi davanti al tribunale militare rivoluzionario francese. Rimini, Il Cerchio, 2002. ISBN: 88-8474-008-8

- A. Maffei. Dalle Pasque Veronesi alla pace di Campoformido. Rimini, Il Cerchio, 2005. ISBN: 88-8474-101-7

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |