Water vole (North America) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Water vole |

|

|---|---|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Arvicolinae |

| Genus: | Microtus |

| Species: |

M. richardsoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Microtus richardsoni (De Kay, 1842)

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The water vole (Microtus richardsoni) is the biggest North American vole. You can find it in the northwestern United States and southern parts of western Canada. For a long time, people thought this animal belonged to the Arvicola group. But new genetic tests show it's actually more closely related to other North American Microtus species. Water voles are on a special list from the USDA Forest Service. This is because their populations are very small, and their homes might be shrinking.

These animals have fur that is gray-brown or red-brown. Their bellies are gray. They have large back feet, which make them amazing swimmers! You can find them in high mountain meadows or semi-mountain areas near water. They eat grasses, leaves, roots, and seeds. Sometimes they also eat small bugs. Water voles dig tunnels that connect to water. This is why they are called "semi-aquatic," meaning they live partly in water.

Water voles are active all year, even digging tunnels through the snow in winter. Their burrows often have entrances right at the water's edge or even under the water. They usually live in groups of 8 to 40 voles along waterways.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The word "vole" first appeared around 1805. It's a short version of "vole-mouse," which means "field mouse." The word "vole" comes from the Norwegian word "vollmus." "Voll" means field, and "mus" means mouse. It might also have been influenced by the Swedish word "vall," which also means field.

The Microtus richardsoni is also known by many other names. Some of these are Richardson's water vole, Richardson vole, Richardson's meadow vole, water rat, and giant water vole.

Water Vole Family Tree

Even though this animal was once thought to be part of the Arvicola group, genetic evidence shows it's closer to North American Microtus species. Scientists have done DNA tests that suggest the closest relative to Microtus richardsoni is the meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus).

Old fossil evidence suggests that the M. richardsoni came from an ancient type of vole called Mimomys in Siberia. This happened about 1.5 million years before the Arvicola group appeared in Europe. This makes scientists think the water vole is a very old type of Microtus. The similarities between M. richardsoni and Arvicola are likely because they developed similar traits for similar lifestyles, not because they are closely related. Today, there are about 62 different species in the Microtus group.

How They Look

Water voles have unusually large back feet. These feet are usually between 25 and 34 millimeters long. This helps tell them apart from other small rodents and makes them fast in the water. Male water voles are usually bigger than females.

On average, these animals are about 20 to 27 centimeters long, including their tail. Their tails are usually 6 to 10 centimeters long. They weigh between 125 and 178 grams. The water vole is the second largest rodent in its area, after the muskrat.

Their fur is grey-brown, dark brown, or reddish-brown on their backs. Their undersides are grayish-white. Water voles have large front teeth (incisors). They also have a very large skull and strong cheekbones. These features help them dig tunnels well and chew through tough roots easily.

Water Vole Life

Where They Live and What They Eat

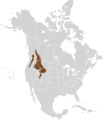

Water voles live in two main areas across the western United States and Canada. These areas stretch from British Columbia and Alberta through parts of Oregon, Washington, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. They live in high mountain or semi-mountain meadows near water. They are usually found between 914 and 3,201 meters high.

Their homes can be very different from place to place. This is because of natural barriers like large forests, mountains, and big valleys without water. However, genetic studies show that water voles can travel over land to find other groups and reproduce. This travel between groups happens more often with nearby populations. Because water voles live in small, separate areas, it's important for them to be able to move between these groups. This helps balance out when a local group might die out.

Their main food is plants, including leaves, stems, grasses, and willows. Sometimes they eat seeds or insects. What they eat can change a lot depending on where they live. Studies show that water voles have a very fast metabolism. This means they don't have to eat as much food as other rodents their size. Most often, water voles eat the parts of plants that grow underground. These are available to them all year. There is no sign that they store food for winter. In winter, they dig tunnels through the snow. They usually stay under the snow once it's about 6 centimeters deep. This can be for about 7 to 8 months of the year.

Water voles are most active at night. They travel between tunnels, nests, and water using paths on the surface. These paths are 5 to 7 centimeters wide through the plants. Often, the entrances to their tunnels or burrows are found at the water level or under the water along river banks. They build these tunnels and nests just below the plant roots, about 4 to 6 centimeters underground. They do this during their breeding season, from June through late September. Females give birth and care for their babies in these underground nests, which are lined with leaves and grass.

Social Life and Reproduction

Water voles are usually found within 5 to 10 meters of water. They have a social system where one male mates with several females. Females tend to stay in their own areas, which don't overlap with other females. Males travel between burrows to mate with different females. Because of this, males travel over a much larger area than females. Males also tend to be more aggressive than females, especially during the breeding season. Females become ready to mate when they are around active males. This usually happens when plants start growing in the spring.

Both male and female water voles have rather large glands on their sides. These glands help them mark their territories. This stops other voles from entering their nests. They also use these scents to signal to mates during the breeding season. Water voles breed for 3 months during the summer. Babies are born from June until late September. Females usually have about 5 to 6 babies in a litter. The shortest time for a pregnancy is 22 days. The number of babies in a litter tends to increase as the mother gets older, ranging from 2 to 10 young. Even though water voles seem able to have many babies, like other rodents, their group sizes stay very small, usually 8 to 40 individuals. This might be because their breeding season is very short compared to other rodents, who breed for 6 months or more.

Birthing and Parental Care

Newborn voles are born without fur and cannot see. They weigh about 5 grams. They can make sounds right away. Within 3 days, they start to grow fur. By day 10, they are running and climbing. By day 17, they can swim on their own. The mother feeds them milk until they are 21 days old. They stay in the nest together for about 32 days. During this time, the babies grow about 1.24 grams per day. Even though they might still be in the nest with their mother, she provides very little care after they stop drinking milk. Around 40 days old, they move to their own nests. About 3 weeks later, they are old enough to reproduce themselves.

About 26% of young males and females start to reproduce during the same breeding season they were born. However, adult voles who lived through the winter are responsible for most of the reproduction. Some adult females might have up to two litters in one breeding season. Among adults who lived through the winter, 90% of females and 100% of males are able to reproduce.

How Long They Live

Studies show that for every adult vole that dies, a young vole takes its place. Most water voles only live through one winter. They usually die at the end of their second breeding season. Very few adults survive two winters.

Why Water Voles Are at Risk

Scientists have studied water vole homes because they have very specific needs. They want to know if grazing by animals or the amount of rain affects vole populations. This helps us protect them. It has been found that more rain creates more good places for water voles to live. In wetter years, young water voles become ready to reproduce sooner. This means they can have more babies. The average number of babies in each litter also increased.

It has also been found that grazing by animals affects water vole populations. In areas with light or moderate grazing, not as many young voles survived. The group sizes were also much smaller than in other areas. Where there was severe grazing, it damaged the stream bank so much that it was no longer a good home for them. Farm animals can cause many harmful changes to the water vole's home. They can compact the soil, increase water runoff, break stream banks, and cause erosion. They also eat the plants that voles use for cover and food. Lots of ferns, mosses, and shrubs are very important ground cover to protect water voles from predators. In grazing areas, these plants were rare or gone. Because of this, water voles were not often found in these places.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Microtus richardsoni para niños

In Spanish: Microtus richardsoni para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |