William Keogh facts for kids

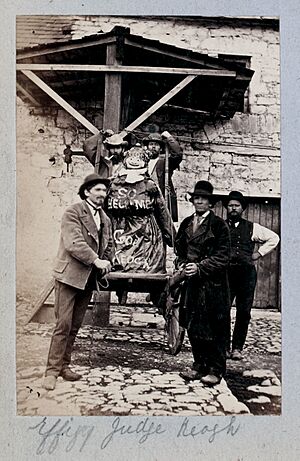

William Nicholas Keogh (1817–1878) was an Irish politician and judge. He was known for being a controversial figure whose actions were seen by many as a betrayal of his political promises. His name became a symbol in Ireland for someone who goes against their word.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Keogh was born in Galway. His father, also named William Keogh, was a clerk for the Crown in Kilkenny. William attended Dr. Huddard's school in Dublin and later studied at Trinity College Dublin. He became a lawyer in 1840 and a senior lawyer (called Queen's Counsel) in 1849.

People always recognized his intelligence. He was an excellent speaker, both in public and private. He even started a well-known debating group called the Tail-end Club. Keogh wrote several books about law, politics, and literature, including one about the writings of John Milton.

When he was young, he was known for being friendly, good-humored, and a great talker. He joined the legal circuit in Connaught where he quickly gained many clients. This was more due to his powerful speaking skills and impressive presence than his legal knowledge. These talents soon led him towards a career in politics.

Family Life

In 1841, William Keogh married Kate Rooney, whose father was a surgeon from Galway. They had one son and a daughter named Mary. Mary later married James Murphy, who became a judge of the High Court. They had six children together.

Political Journey

In 1847, Keogh was elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Athlone. In 1851, he helped create the Catholic Defence Association. This group worked to support farmers' rights. He was re-elected for Athlone in 1852.

In that same year, he helped form the Independent Irish Party, which was also known as "the Pope's Brass Band." This new party promised to cancel the Ecclesiastical Titles Act and to continue fighting for tenant reform. Most importantly, its members made a clear promise not to accept government jobs. Instead, they aimed to hold the balance of power in the British Parliament. At first, they succeeded, helping to vote out the government led by Lord Derby.

However, just a few months after promising not to take office, Keogh and his colleague John Sadleir made a decision that damaged his reputation for the rest of his life and beyond. He accepted a position in the new government. He first became the Solicitor-General for Ireland, and then the Attorney-General for Ireland in 1855.

Many Irish people saw this as an unforgivable breaking of a serious promise. His name, along with Sadleir's, became a common term in Irish politics for someone who betrays their principles. Even a century later, a politician named John A. Costello turned down an offer to become a judge because he didn't want to be accused of being "another Sadleir or Keogh."

Judicial Career

In 1856, Keogh was appointed a judge of the Irish Court of Common Pleas. Everyone agreed he was very qualified for the job because of his legal skills. In cases that were not about politics, he had a good reputation. He might not have been the deepest legal thinker, but he could quickly understand the main point of a case.

Unfortunately, his behavior as a judge did not help his reputation. He had strong opinions and always expressed them forcefully. His quick temper often led to arguments with the lawyers. Once, Peter O'Brien, who later became a very important judge, was threatened with being removed from the courtroom. However, Keogh later apologized to O'Brien in front of everyone in court. This suggests that Keogh, who was known for being friendly when he was younger, might have been suffering from stress or poor health rather than acting out of bad intentions.

Keogh's handling of the "Fenian Trials" in 1865–1866 and the harsh sentences given were heavily criticized. Some people defended him, saying that at least one person, Charles Kickham, was treated as fairly as possible based on the evidence.

His reputation was further damaged by his decision in the Galway election case of 1872. In this case, the losing candidate, William Le Poer Trench, asked for the winner, John Philip Nolan, to be removed from office. Trench claimed there had been threats and unfair pressure from Catholic priests. Keogh's judgment took nine hours to read and was seen as very biased. It did not help the reputation of the judges. Much of his speech seemed to be an angry attack on the Catholic Church leaders. This seemed very strange coming from someone who used to be part of "the Pope's Brass Band." There was a huge public outcry, and the government had to work hard to stop a motion in Parliament that called for Keogh to be removed from his job. Because of his judgment, government lawyers felt forced to prosecute Patrick Duggan, the Bishop of Clonfert, and they were clearly relieved when he was found not guilty.

Friendship with Father Healy

Keogh became close friends with Father Healy of Little Bray. They would often have dinner at each other's homes every week. Father Healy's open-mindedness and sense of humor appealed to the judge, who was a bit unconventional. Father Healy continued to support Keogh through his disagreements with the Church and during times when Keogh was struggling with his mental health.

A funny conversation between them was once written down:

"My dear Healy," said Keogh, with a very serious face, "I'll do anything you wish - only name it. I'd turn Turk or Mohammedan if it serves you."

"Turn Catholic," replied Healy.

Final Years and Death

In his later years, Keogh showed more and more signs of being eccentric. He faced constant public dislike from many Catholic people. His public argument with Peter O'Brien, which likely happened in 1877, suggests that his bad temper was due to stress rather than a mean personality. Stories from Oliver Burke show that Keogh could still be charming and good-humored at times.

In 1878, he traveled to Belgium and Germany to try and improve his health. However, on August 19, 1878, he had a fit of confusion and attacked his valet. He was then taken to a hospital. While he may have regained his clear thinking, his body continued to weaken. He died in Bingen am Rhein on September 30, 1878, and was buried in Bonn.

Legacy

Keogh's death did not reduce the strong dislike for him in Ireland. Irish newspapers wrote many negative things about him. This led The Times newspaper in London to comment that in any other country, his talents would have made him popular and respected.

There is no doubt about his intelligence. His friends remembered the charm and good humor he showed in his younger years. His son-in-law, Mr. Justice James Murphy, who was close to him, defended him until the end. A book called Anecdotes of the Connaught Circuit, published a few years after Keogh's death, mostly paints a positive picture of him.

However, as one writer, McCullagh, points out, not many politicians damage their reputation so much that people still speak of them with disrespect a century later. Despite Keogh's talents, it seems that much of the harm to his reputation was caused by his own actions.

The words on the Cormack brothers memorial at Loughmore – placed there 32 years after Keogh's death – show how much hostility there still was towards him.

Arms

|

|

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |