Wolfgang Zuckermann facts for kids

Wolfgang Joachim Zuckermann (born October 11, 1922 – died October 30, 2018) was an American harpsichord maker and writer. He was born in Germany. He became famous for creating a very popular kit that allowed people to build their own harpsichords. He also wrote an important book called The Modern Harpsichord. Later in life, he became a social activist and wrote other books like The Mews of London and The End of the Road.

Contents

Early Life and Moving to America

Wolfgang Zuckermann was born in Berlin, Germany. His family was Jewish and loved learning. He was named Wolfgang after famous artists Goethe and Mozart. He had two brothers, Alexander and Michael. From age eight, Wolfgang played the cello, and his family even had their own string quartet.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany, Wolfgang's family had to leave their home. They moved to New York in 1938. That same year, Wolfgang became an American citizen and started using the name "Wallace" or "Wally." He served in the U.S. Army during World War II. After the war, he went to Queens College in New York, where he studied English and psychology and graduated with high honors.

Becoming a Harpsichord Builder

After college, Wolfgang tried working as a child psychologist, but he didn't enjoy it much. Instead, he decided to learn how to repair and tune pianos. He soon started buying, fixing, and selling old pianos.

Wolfgang also loved playing Baroque chamber music, which often uses a harpsichord. This led him to become interested in building harpsichords himself. He built his first one in 1955. He taught himself how to build them by visiting workshops and museums. He even got to see old harpsichords in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum.

At that time, more and more people were becoming interested in Baroque music and playing instruments the way they were played long ago. There were also very few harpsichord makers in America. So, Wolfgang's harpsichords were in high demand, and his business grew quickly. By 1960, he had sold many instruments.

The Harpsichord Kit Idea

Wolfgang realized he was spending too much time fixing harpsichords for his customers. He thought, "What if people could build their own instruments?" This way, they would know how to fix them too.

So, in 1960, he came up with the idea of selling "do-it-yourself" harpsichord kits. This idea was a huge success! These kits, sometimes called the 'Model T' harpsichord, sold to thousands of people, schools, and musicians all over the world. By 1969, over 10,000 kits had been sold. Many famous harpsichord builders today started by building a Zuckermann kit.

At first, the kits were very basic and affordable. They didn't include all the wooden parts. But over time, the kits became more complete. Wolfgang also started offering kits for other instruments like the spinet harpsichord and the clavichord.

How the Kits Were Made

The main place for making the kits was Wolfgang's workshop in Greenwich Village, New York. Some parts were made in the shop, but many were made by larger factories. For example, the wooden parts for the harpsichord case needed to be cut very precisely. Keyboards, which are hard to make, were bought from other companies. Even the special plywood for the soundboard had to be custom-ordered from a factory.

Who Bought the Kits?

Wolfgang's harpsichord kits became incredibly popular. People of all ages built them and gave them nicknames like the "Slantside" or the "Z-box."

In the 1960s, people had more free time and enjoyed building things themselves, like model airplanes. So, building a harpsichord kit was a fun and challenging hobby. Wolfgang found that many of his customers were educated people, especially those living in college towns.

Interestingly, many kits were sent to soldiers serving in the Vietnam War. One Navy officer even had his clavichord on an aircraft carrier! Soldiers found that building these instruments helped them deal with loneliness or stress.

The Z-box Harpsichord Design

The Zuckermann kit harpsichord was designed to be affordable and easy for amateurs to build. This meant it wasn't exactly like the old harpsichords from history. For example, it had straight sides instead of curved ones, and it used plywood for some parts.

Over time, harpsichord makers started to focus more on building instruments exactly like the old ones. Wolfgang's company, after he left, also moved towards making more historically accurate instruments.

The Modern Harpsichord Book

Around 1967, Wolfgang traveled a lot, visiting harpsichord workshops in America and Europe. He wrote about what he learned in his 1969 book, The Modern Harpsichord. This book looked at many harpsichord makers of the time and their ideas.

The main message of the book was that harpsichords should be built using historical methods. This means making them lightweight, like the instruments from the 16th to 18th centuries. Wolfgang believed that old builders had already found the best ways to create beautiful sounds. He thought that many new harpsichords, built using piano-making ideas, sounded weak and were hard to keep in good condition.

Wolfgang praised makers who followed historical principles, like Frank Hubbard and William Dowd. He also strongly criticized larger companies that built heavy, non-historical instruments. For example, he said one company's instrument "suffers from laryngitis, possessing a coarse, whispering tone."

The book had a huge impact. Many people say it changed how modern harpsichords are built. It helped the idea of historically accurate harpsichords become popular, which is how most harpsichords are made today. The book was so critical of some German makers that it was even banned in Germany for a while.

Leaving the Harpsichord Business

After writing his book and learning so much about historical instruments, Wolfgang decided to stop making his less-than-historical kits. In 1970, he sold his kit business to David Jacques Way. David Way continued the company, but he changed its focus to building more historically accurate instruments, using Wolfgang's research. The company is still in business today.

Even though he moved on, Wolfgang stayed involved in the harpsichord world for some time. He designed new historical instrument kits and wrote columns for a harpsichord magazine.

Supporting the Arts

While he was making harpsichords, Wolfgang also supported the performing arts. In 1963, he helped start the Sundance Festival of the Chamber Arts in Pennsylvania. This festival had classical concerts, puppet operas, theater, dance, and poetry. Famous harpsichord players performed there.

Later, Wolfgang and his friend Michael Smith also helped run Caffe Cino, a coffee house that was also an off-off-Broadway theater in New York City. The theater was known for showing new and sometimes daring plays.

As an Activist

In the 1960s, the Vietnam War was happening, and many Americans protested against it. Wolfgang was strongly against the war. He became more involved in political activism after seeing protests and even being jailed once. He helped organize "Angry Arts week" to encourage artists to oppose the war.

By 1969, Wolfgang was so upset about the war that he decided to leave the United States. He moved to England, where he bought an old 15th-century house in the countryside. There, he started a crafts business and worked with young people.

Wolfgang then focused more on being a political activist. He worked on projects that encouraged people to live differently from the usual consumer society. In London, he wrote a book called The Mews of London about old stable areas that had become unique living spaces.

In 1987, Wolfgang started working with The Commons, a research group in Paris. He helped with a program called the New Mobility Agenda, which looked for new ways to organize transportation and daily life to make it easier for people to get around. This project led to his book End of the Road (1991), which explained these ideas in a simple way for everyone. He also co-wrote a children's book called Family Mouse Behind the Wheel and helped with the Car Free Days program.

In 1994, Wolfgang helped create "Consumer Holiday," a day to think about how much we consume. This idea later joined with a similar project to become the International Buy Nothing Day program, which still exists today. Around 1995, Wolfgang moved to France and continued his research and writing there.

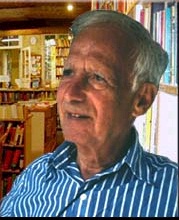

As a Bookstore Owner

In 1994, Wolfgang opened a bookstore and arts center in Avignon, France, called Shakespeare. It was named after a famous English bookstore in Paris from the early 1900s.

The bookstore was described as a cozy place where customers spoke quietly and treated books with respect. Wolfgang himself was often there, creating a calm atmosphere. He even served English cream tea with homemade scones! He retired from the bookstore in 2012, but it is still open today. Wolfgang Zuckermann passed away in Avignon, France, in late 2018.

Images for kids