Wright brothers patent war facts for kids

The Wright brothers patent war was a big legal fight over their invention of airplane flight control. The Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville, were American inventors. Many people believe they built the world's first successful airplane. They also made the first controlled, powered, and long-lasting human flight on December 17, 1903.

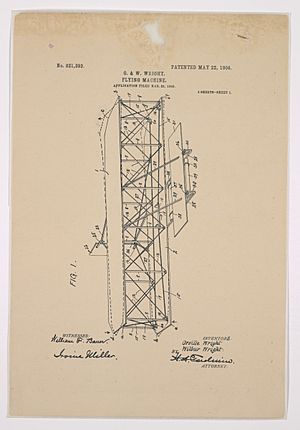

In 1906, the Wrights got a U.S. patent for their special way of controlling an airplane. A patent is like a legal document that protects an invention. In 1909, they sold this patent to a new company called the Wright Company. They got a lot of money and a share of the company.

This company then started the "patent war." They wanted to be the only ones making airplanes in the U.S. When that didn't work, they sued other pilots and companies. One famous person they sued was Glenn Curtiss, another early airplane inventor. They wanted him to pay them money for using their ideas.

In 1910, the Wrights won their first lawsuit against Curtiss. A judge said that Curtiss was using the Wrights' invention without permission. The judge ordered Curtiss to stop. The Wright brothers eventually won every case they brought in U.S. courts.

Even after Wilbur Wright died, and Orville Wright retired in 1916, the patent war kept going. Other companies even started their own lawsuits. Many historians think this legal fighting slowed down airplane development in the U.S. Because of this, American pilots in World War I had to fly European planes. After the war began, the U.S. government made airplane companies share their patents.

Contents

How the Wright Brothers Patented Flight Control

During their experiments in 1902, the Wright brothers learned how to control their glider. They could control its movement in three ways: up and down (pitch), side to side (roll), and turning left or right (yaw). Their big discovery was using wing-warping for roll control. They used a rear rudder for yaw control and a front elevator for pitch control.

In March 1903, they asked for a patent for their control method. They wrote the application themselves, but it was turned down. In 1904, they hired a patent lawyer named Henry Toulmin. On May 22, 1906, they received U.S. Patent 821,393 for a "Flying Machine."

This patent was important because it protected their new way of controlling a flying machine. It didn't matter if the machine had an engine or not. The patent described how to twist the wings (wing-warping). But it also said that other methods, like ailerons, could be used. Ailerons are small flaps on the wings that help control the plane's roll.

Wilbur Wright wrote letters in 1910 about their invention. He said that everyone using their control system owed it to them. He believed they deserved credit for the way airplanes were controlled.

U.S. courts agreed that ailerons were covered by the Wrights' patent. This meant the Wrights won lawsuits against inventors like Glenn Curtiss. These inventors used ailerons to control their planes, similar to what the Wrights described.

The Patent War Begins

|

|

|

| Wilbur Wright | Orville Wright | Glenn Curtiss |

|---|

After the Wright brothers showed their airplane, many others tried to claim credit. The New York Times said in 1910 that before the Wrights, all flying attempts failed. But after them, everyone seemed able to fly. This led to a "patent war" with many lawsuits.

In 1908, the Wrights warned Glenn Curtiss not to use their patent for profit. Curtiss refused to pay them. He sold an airplane to a group in New York in 1909. So, the Wrights sued him, starting a long legal fight.

They also sued foreign pilots who flew in U.S. shows, like French pilot Louis Paulhan. Some people joked that the Wrights would sue if someone just jumped and waved their arms.

The Wrights' companies in Europe also sued manufacturers there. These lawsuits were not always successful. In Germany, a court said the patent wasn't valid. This was because Wilbur Wright and Octave Chanute had talked about their ideas publicly before.

In the U.S., the Wrights made a deal with the Aero Club of America. This allowed airshows approved by the Club to happen without legal threats. Show organizers paid fees to the Wrights.

The Wright brothers won their first case against Curtiss in February 1913. But Curtiss appealed the decision. The Wrights also contacted Samuel Franklin Cody in the UK. They claimed he used their patent. But Cody said he used wing-warping on his kites even before their flights.

The Wrights focused so much on legal issues that they didn't develop new planes as quickly. By 1910, other European companies made better aircraft. Some say this slowed down U.S. aviation. When the U.S. entered World War I, they had to use French airplanes.

However, some researchers disagree. They say that before World War I, airplane makers didn't face patent problems. Others supported the Wrights. They compared it to Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison. Their lawsuits didn't stop their inventions from being widely used.

In January 1914, a U.S. court supported the Wrights' win against Curtiss. But Curtiss kept using legal tricks to avoid paying.

To fight back, Glenn Curtiss and the Smithsonian Institution tried to make it look like Professor Samuel P. Langley's failed 1903 plane could fly. They secretly changed it. After showing it could fly, they changed it back to its original state. It took until 1928 for the Smithsonian to admit the Wright brothers deserved credit for the first successful flight.

A lawyer named Russell Klingaman later studied the Wright-Curtiss lawsuit. He found problems with how the case was handled. He believes the judge made mistakes and that the Wrights' lawyer met privately with the judge.

After the Wrights' Patent Battles

After Wilbur Wright died, Orville Wright left their company in 1916. He sold his rights to their important patent for a lot of money. His company merged with another, forming the Wright-Martin Corporation. This new company continued the patent battles. They wanted to get back the money they invested.

At the same time, Glenn Curtiss and his company also fought over their patents. This made airplanes in America very expensive.

Lawsuits scared many people away from making aircraft. This happened just as the war in Europe was starting. The U.S. military needed more planes. But they found it hard to get enough from manufacturers.

In December 1916, Wright-Martin demanded that other companies pay them money for each plane sold. They wanted a fee for all aircraft. This included planes using the Wrights' older wing-warping method or the more popular ailerons.

A Solution: The Patent Pool

By 1917, the two main patent holders, the Wright Company and the Curtiss Company, had stopped new airplane building in the U.S. This was a big problem as World War I began. The U.S. government stepped in. They followed advice from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. They pushed the industry to create a "patent pool."

This patent pool was called the Manufacturer's Aircraft Association. All airplane makers had to join. Each member paid a small fee for every plane they built. Most of this money went to the Wright-Martin and Curtiss companies. This continued until their patents ran out.

This agreement was meant to last only during the war. But in 1918, the lawsuits were not started again. By then, Wilbur had died, and Orville had sold his share of the company. The "patent war" finally ended.

What Happened Next

The lawsuits hurt the public image of the Wright brothers. Before, people saw them as heroes. Critics said their actions might have slowed down aviation. They compared them to European inventors, who shared their ideas more openly.

The Manufacturers Aircraft Association was an early example of a government-backed patent pool. This idea has been used in modern times. For example, it helped make HIV medicines more available in Africa.

The Curtiss and Wright companies later merged in 1929. They formed the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which still exists today.

Who Invented What First?

There are different ideas about who first invented ailerons for flight control. In 1868, a British inventor named Matthew Piers Watt Boulton patented ailerons. This was about 40 years before ailerons became common. His patent was forgotten for a long time.

Aviation historian Charles Gibbs-Smith said in 1956 that if Boulton's ailerons had been known, the Wright brothers might not have been able to patent lateral control. However, the judge in the Wright-Curtiss lawsuit, John R. Hazel, disagreed. He said Boulton's ideas were too unclear to teach others how to build them.

American inventor John Joseph Montgomery also experimented with ways to control gliders. In 1885, he used spring-loaded flaps for roll control. Later, he used wing-warping on his gliders from 1903 to 1905. He patented his wing-warping system around the same time as the Wrights. People often asked him to share his patent to avoid the Wright brothers' lawsuits.

New Zealander Richard Pearse might have flown a powered plane with small ailerons as early as 1902. But his claims are debated. Even by his own accounts, his aircraft were hard to control.

Robert Esnault-Pelterie, a Frenchman, built a glider in 1904. It used ailerons instead of wing-warping. Even though Boulton had patented ailerons in 1868, Esnault-Pelterie was the first to actually build them.

The Santos-Dumont 14-bis biplane added ailerons in late 1906. But it was never fully controllable. The Blériot VIII was the first plane to use a modern joystick and rudder bar. It used wingtip ailerons for roll control in 1908. Henri Farman's ailerons on the Farman III in 1909 were the first to look like modern ailerons.

In 1908, U.S. inventor Glenn Curtiss flew a plane controlled by ailerons. Curtiss was part of the Aerial Experiment Association, led by Alexander Graham Bell. This group developed ailerons for their June Bug plane. Curtiss made the first officially recognized flight over a kilometer in the U.S. in this plane. In 1911, the Association's aileron design received a patent.