Y Sap mine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Y Sap mine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of the Somme, First World War | |||||||

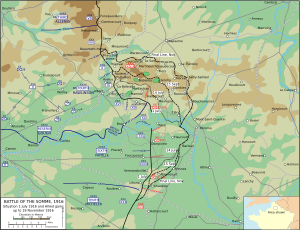

Battle of the Somme 1 July – 18 November 1916 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Douglas Haig | Erich von Falkenhayn | ||||||

The Y Sap mine was a huge underground bomb used by the British army during the First World War. It was secretly placed under German lines and set to explode on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

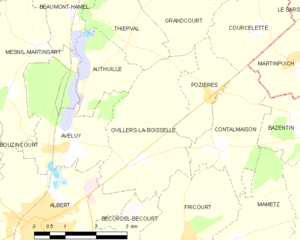

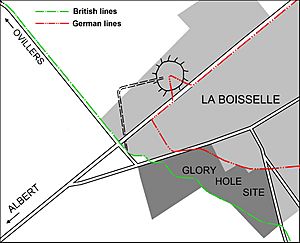

This giant bomb was dug by special British soldiers called the Tunnelling Companies of the Royal Engineers. They dug it under a German machine-gun spot known as Blinddarm (which means 'appendix' in German). This spot was near the village of La Boisselle in France. The mine was named Y Sap after the British trench it started from. It was one of 19 mines that were blown up by the British at the start of the battle.

The Y Sap mine exploded at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916, creating a very large hole in the ground. However, the explosion did not help the British attack as much as planned. German soldiers had overheard British messages and moved their machine guns away from the Blinddarm spot. When the British soldiers attacked, the Germans were ready and fired at them from other positions. The British 34th Division suffered the most losses of any division that day. The Y Sap mine crater was filled in after the war and cannot be seen today.

Why Dig Underground?

Warfare Below Ground in 1914

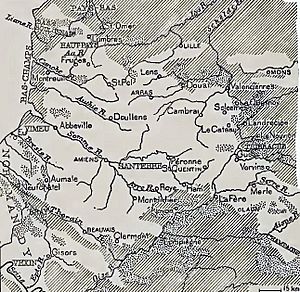

Warfare on the Somme front began in September 1914. German troops tried to move west towards Albert but were stopped by French soldiers near La Boisselle. Both sides then started to dig in, creating strong underground tunnels and positions.

On 18 December 1914, French soldiers captured a cemetery in La Boisselle. They set up a forward post very close to the German front line. By Christmas Day 1914, French engineers began digging the first mine shaft in La Boisselle.

Underground Battles in 1915

Fighting continued fiercely in the "no man's land" (the area between the two armies) near La Boisselle. Even when other parts of the front were quiet, the underground war kept going. On the night of 8/9 March, a German tunneller accidentally broke into a French tunnel that was already packed with explosives! A group of brave German volunteers spent 45 minutes carefully taking the bomb apart.

From April 1915 to January 1916, 61 mines were exploded around a key area called L'îlot (which the Germans called Granathof, or Shell Farm). Some of these mines contained huge amounts of explosives, up to 25,000 kilograms (about 55,000 pounds).

In July 1915, British soldiers took over positions from the French north of the Somme. The British formed their own special Tunnelling Companies, like the 178th and 179th, to continue the underground war. The area near La Boisselle was very narrow, sometimes only 50 yards (about 45 meters) wide. It was full of craters from previous explosions.

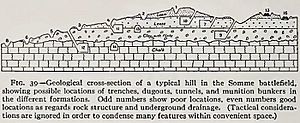

Keeping the underground work secret was very important. The British front line did not run continuously through this area, so soldiers defended the mine shafts with special posts. The underground war involved digging tunnels to destroy enemy strong points and also digging defensive tunnels to stop enemy tunnels. Around La Boisselle, the Germans dug tunnels parallel to their front line to defend against British attacks.

On 19 November 1915, Captain Henry Hance, who led the 179th Tunnelling Company, thought the Germans were very close to their tunnel. He ordered 6,000 pounds (about 2,700 kg) of explosives to be placed in their mine chamber. Early on 21 November, the Germans blew their own mine. This explosion caused the British mine to explode too, filling their tunnels with dangerous gas.

Preparing for the Big Attack

Plans for 1916

The Battle of Albert (1–13 July) was the first part of the Battle of the Somme. La Boisselle was right in the middle of the British attack. The Tunnelling Companies of the Royal Engineers had a big job. They had to place 19 mines under German positions. They also had to dig shallow tunnels called "Russian saps" from the British front line into no man's land. These would be opened at the exact moment of the attack, allowing soldiers to start their charge from a shorter distance.

At La Boisselle, the British prepared four mines. Two were at L'îlot to destroy German tunnels. Two more, Y Sap and Lochnagar, were placed to help the attack on either side of the German strongholds in the village.

In early 1916, British scouting parties found that the German Blinddarm strongpoint (Y Sap to the British) was protected by deep mines. The Y Sap mine was dug right under this Blinddarm strongpoint, which overlooked a valley called Mash Valley.

The Y Sap mine tunnel started from the British front line. It had to be dug in a zigzag pattern because the Germans had tunnels 30 to 120 feet (9 to 36 meters) deep. The tunnel went about 500 yards (457 meters) into no man's land, then turned right for another 500 yards. About 40,000 pounds (18,000 kg) of explosives were placed in the chamber under the Blinddarm.

To keep their work secret, the tunnellers used bayonets with special handles and worked barefoot on floors covered with sandbags. They carefully removed flints from the chalky ground. The dirt they dug out was put into sandbags and passed along a line of miners. This dirt was later used to pack the explosives tightly. The Y Sap and Lochnagar mines were "overcharged" (filled with extra explosives) to make sure they created very large craters.

Captain Henry Hance, the commander of the 179th Tunnelling Company, suggested blowing up the Y Sap mine two days early. He believed this would destroy the Blinddarm and stop German machine guns from firing along the British lines during the attack. He also thought the British could then take over the crater and use it as a closer starting point for their attack. However, his superiors decided against it. They worried that an early explosion would warn the Germans that a big attack was coming.

The Battle Begins

1 July 1916

The four mines at La Boisselle exploded at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916. The Y Sap and Lochnagar mines were the biggest mines ever detonated at that time. The explosions were so loud that some people reported hearing them all the way in London!

The Y Sap mine created a huge crater. However, it did not help the British attack as planned. The Germans had found out about the mine in time and moved their soldiers away from the spot. When the British infantry attacked, the Germans were ready. They fired at the British from other positions, especially at the 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigade. This brigade suffered the most casualties of any brigade on the first day of the Somme. Many soldiers were hit even before they reached the German lines. The losses were so severe that the brigade had to be replaced just five days later.

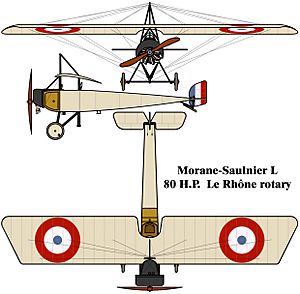

2nd Lieutenant Cecil Lewis, a pilot from 3 Squadron RFC, watched the explosions from his plane, almost 2 miles (3.2 km) away:

We were over Thiepval and turned south to watch the mines. As we sailed down above all, came the final moment. Zero! At Boisselle the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earthly column rose, higher and higher to almost four thousand feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like a silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.

—Cecil Lewis, whose aircraft was hit by lumps of mud thrown up by the explosion.

After the War

After the war ended in 1918, the people of La Boisselle returned and rebuilt their homes. The Y Sap mine crater was filled in and the land was reshaped. Today, you can no longer see the crater.

See also

- List of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |