Ye Antientist Burial Ground (New London, Connecticut) facts for kids

Ye Antientist Burial Ground is a very old cemetery in New London, Connecticut. It's located between Hempstead Street and Huntington Street. People have called it by many names over the years, but they all mean "Ancient Burial Ground." This cemetery is one of the first graveyards in New England and the oldest colonial cemetery in New London County. It covers about 1.5 acres (6,000 square meters) on a hillside, right next to where New London's first meeting house used to be. When it was first settled, the area was called "Pequot Plantation" until 1658. From the cemetery, you can see a wide view of the Thames River to the east and the hills of Groton, Connecticut on the other side.

Contents

History of the Burial Ground

The land for the cemetery was set aside in the summer of 1645. The first adult was buried there in 1652. However, it was a rule made on June 6, 1653, that officially made it a public burial place. This rule stated that it would "ever bee for a Common Buriall place, and never be impropriated by any," meaning it would always be a public cemetery and never owned by one person.

The Sexton's Job

An old record talks about the job of the sexton, who was like a caretaker: The sexton's job was to keep the young people in order during meetings, sweep the meeting house, and make sure dogs stayed out. For this, they earned 40 shillings a year. They also dug all the graves. They got 4 shillings for an adult's grave and 2 shillings for a child's grave, paid by the family.

Early Burials in New London

In the 1600s, New London was a wild and lonely part of early colonial Connecticut. People usually didn't have private burials, so this was the only public burial place.

People would bring the dead from miles away, sometimes carried on special frames or on a stretcher by many people. Large groups would gather and help carry the body, taking turns along the way.

Many of the very first graves didn't have markers with names. New London didn't have skilled stonecutters back then, and the early settlers didn't have much money. Some families later added markers for their loved ones. At least four stones dated in the 1600s were actually placed after 1720.

If an important person in the community died, their friends could only respectfully bury them. They would often place a rough granite stone over the grave. These heavy stones were broken from nearby rocks and dragged to the spot to protect the remains and mark where someone was buried.

Over time, the unmarked burial mounds wore away. Older graves were often covered by new burials. This means we can't tell how many people are buried there just by looking at the remaining markers. But it's believed that most of the first settlers of New London were buried in this ground.

Gravestones and Carvers

In the early 1700s, skilled stone carvers like John Hartshorne and James Stanclift made good quality grave markers for the cemetery. Later in that century, carvers from Eastern Connecticut, such as Josiah Manning, David Lamb, Gershom Bartlett, and Johnathan Loomis, carved stones from granite schist. Carvers from the Portland/Middletown area, like the Thomas Johnson Family and later Stanclifts, made markers from brownstone. You can still see these stones in the cemetery today.

Many wealthy families bought slate gravestones that were brought in from the Boston area or coastal Rhode Island. These stones arrived by ship through the New London Port. You can find work by carvers like the Lamsons of Charlestown, Massachusetts, the John Stevens Shop of Newport, Rhode Island, and James Foster & Sons of Dorchester, Massachusetts, in this cemetery.

Notable People Buried Here

It's important to remember that many of the first settlers might have unmarked graves in this cemetery. Here are some of the known notable people buried here:

- Sarah Kemble Knight (1666–1727): She was an author who wrote "The Journal of Madame Knight" in 1704.

- Gurdon Saltonstall (1666–1724): He served as the Governor of the Colony of Connecticut from 1708 to 1724.

- Lucretia Harris Shaw (1737–1781): She was the wife of Captain Nathaniel Shaw, Jr.. During the American Revolution, she turned her home into a hospital. She cared for soldiers who were sick or wounded after being held on British prison ships. Because of this, she became very sick herself and passed away. A local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution is named in her honor. Her house, the Shaw-Perkins Mansion, has been kept as the headquarters for the New London County Historical Society since 1907.

- Thomas Short (1682–1712): He was a printer who printed "The Saybrook Platform" in 1710.

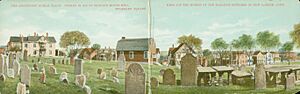

Gallery