Yuquot Whalers' Shrine facts for kids

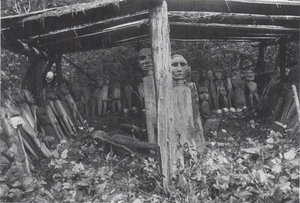

The Yuquot Whalers' Shrine is a special place that was once on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. It was used for purification rituals by the family of a Yuquot chief. This shrine held 88 carved human figures, four carved whale figures, and sixteen human skulls. Since the early 1900s, it has been kept at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. It is not often shown to the public. There are ongoing discussions about returning it to its original home.

Contents

What is the Yuquot Whalers' Shrine?

Early Western explorers first wrote about the Shrine in 1785. They described it as a ceremonial site of the Nootka people, who are now known as the Nuu-chah-nulth. We don't know exactly when the Shrine was first built.

Anthropologist Aldona Jonaitis thinks that a text from 1818 by Camille de Roquefeuil is the first clear proof of the Shrine's existence. The exact rituals performed at the Shrine are a bit of a mystery. Later writings by anthropologists Franz Boas and Philip Drucker mention rituals using skulls or bodies. However, earlier French texts from de Roquefeuil and his ship's surgeon, Yves-Thomas Vimont, do not mention these. What we do know is that the Shrine was very important. The Nuu-chah-nulth people have a long history of whaling, going back at least 4,000 years.

How Was the Shrine Moved?

It is thought that in late 1900 or early 1901, George Hunt learned about this secret Shrine. Hunt was an ethnographer, which means he studied cultures. He was part Tlingit and part English.

In 1903, Hunt contacted Franz Boas about the Shrine. He took many photos to show Boas how interesting it was. Boas was very keen to buy it for his employer, the American Museum of Natural History. Two elders said they had the right to allow the Shrine to be moved. Hunt agreed on a price with them. The condition was that he had to wait until the community left for their hunt. This was because they were worried about a negative reaction from others. In 1904, the Shrine was moved to the museum in New York, where it is today. It has not yet been fully displayed.

The Role of George Hunt and Franz Boas

After the Shrine was moved, George Hunt wrote to Boas. He said, "It was the best thing I ever bought from the Indians." For Boas, getting the Whalers' Shrine was a very important moment. It changed how he thought about museum collections and displays.

Anthropologist Harry Whitehead has spoken out about how George Hunt and Franz Boas collected items. He believes they helped continue a practice called salvage anthropology. This is when people collect objects from cultures they think are "disappearing." Whitehead says that by trying to "save" Nuu-chah-nulth items, they actually sped up the loss of their traditional culture. Also, when these items were shown in public and photographed, it made others want to collect more. This led to many years of misunderstanding and items being taken unfairly.

Aaron Glass, another anthropologist, agrees that Hunt and Boas influenced others. Photographers and anthropologists wanted to capture Nuu-chah-nulth culture before it "disappeared." This continued the practice of salvage ethnography. He mentions that famous photographer Edward Curtis was inspired by Hunt's photos. Curtis sometimes changed things for his pictures to make them more dramatic. This helped create a romantic idea of a "lost culture." In 1910, George Hunt even dressed up as a Nuu-chah-nulth person. He did this to show his version of certain ceremonies for Curtis's camera. However, George was actually acting out a Kwakiutl ceremony from eastern Vancouver Island, which he knew well.

Returning the Shrine Home

Returning the Shrine and its contents is a complex issue. Canada does not currently have laws about returning cultural items. However, museums often act as caretakers and decide what to do case by case. In the United States, there is a law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). This law requires Native American cultural items to be returned to their direct descendants.

One idea for the Shrine is to build a community center to house it, or to build a copy of the Shrine. However, Jonaitis explains that we need to understand the history better. Events before and after the Shrine was taken have made it hard to return it. This is because some of the old ceremonies and traditions for handling such sacred items have been lost. A 1994 documentary called 'Washing of Tears' by filmmaker and anthropologist Hugh Brody was about the return of the Whalers' Shrine.

Why is the Shrine Important?

Canada has recognized the Whalers' Shrine Site as a national historic site since 1983. This means it is an important part of Canada's history and heritage.

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |