Æthelstan A facts for kids

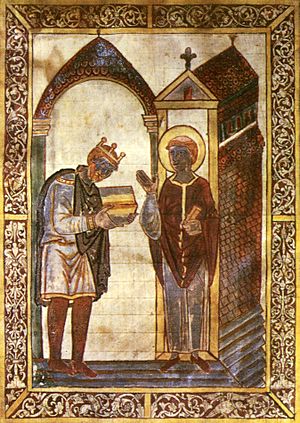

Æthelstan A (/ˈæθəlstæn ˈeɪ/) is the name historians gave to a special, unknown scribe. This scribe wrote important documents called charters (or diplomas) for King Æthelstan of England. These charters were like official papers where the king gave land to people. Æthelstan A wrote them between the years 928 and 935.

These documents are very helpful for historians. They give much more information than other charters from that time. They show the exact date and place where the land was given. They also have a very long list of people who witnessed the grant. These witnesses sometimes included Welsh kings, and even kings from Scotland and Strathclyde.

The charters written by Æthelstan A started soon after King Æthelstan took control of Northumbria in 927. This made him the first king to rule all of England. The charters gave the king grand titles like "King of the English" and "King of the Whole of Britain." Historians believe this showed the king's new, higher status.

These documents were written in a very fancy Latin style called the hermeneutic style. This style became popular in English writings from the mid-900s. It was also a key part of a big religious movement called the English Benedictine Reform. Some experts think this style was "pretentious" or "hard to understand." But others call it "poetic" and "fascinating."

Æthelstan A stopped writing charters after 935. The scribes who came after him used a simpler style. This suggests that Æthelstan A worked alone, rather than being part of a big royal writing office.

Contents

Who Was Æthelstan A?

For a long time, historians wondered if official royal documents were made by a royal office or by monasteries. In the early 1900s, a scholar named W. H. Stevenson suggested that the same person wrote charters in different parts of England. This idea supported the view that royal clerks, who traveled with the king, wrote them.

Later, in 1935, a German scholar named Richard Drögereit studied original charters. He looked at the handwriting and identified three main scribes. He named them Æthelstan A, Æthelstan C, and Edmund C. Today, we know of about twenty "Æthelstan A" charters. Only two of these are original documents; the rest are copies.

The parts of Æthelstan A's charters that described land boundaries were written in correct Old English. This makes it unlikely that he was from another country. Also, the lists of witnesses in his charters always placed Bishop Ælfwine of Lichfield in a higher spot than his rank usually allowed.

King Æthelstan likely grew up in Mercia, a part of England. Historian Sarah Foot thinks the king might have been very close to Bishop Ælfwine. She suggests that Ælfwine might have been Æthelstan A. This is because Ælfwine stopped appearing on witness lists around the same time Æthelstan A stopped writing charters.

Other historians think Æthelstan A was a priest from Mercia who worked for the king. They believe he learned his skills in a religious house in Mercia. He might have respected Ælfwine because they were both from Mercia. It's also possible Æthelstan A had a connection to Glastonbury Abbey in Wessex. This abbey was a center of learning back then.

Why Were These Charters Important?

The first charter Æthelstan A wrote in 928 called the king rex Anglorum, which means "king of the English." This was the first time this title was used! By 931, the king was called "king of the English, raised by God's hand to the throne of the whole kingdom of Britain."

Some charters were witnessed by Welsh kings, and sometimes even by the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde. This showed that these kings accepted Æthelstan's leadership. Historians believe it's no accident that these special charters started right after Æthelstan conquered Northumbria. Æthelstan A's main goal was to show how grand Æthelstan's kingship was.

Before 928, charters were made in different ways. Sometimes royal priests wrote them, and sometimes other priests wrote them for the people receiving the land. But Æthelstan A was the only one writing charters between 928 and 934. This shows that King Æthelstan took strong control over this important part of his royal duties.

In 935, Æthelstan A started sharing the work with other scribes, and then he seemed to retire. His charters have unusually long lists of witnesses. For example, one charter from 931 had 101 names! Another from 934 had 92 names. The witness lists for King Æthelstan's father and grandfather were much shorter. This suggests that King Æthelstan held larger meetings.

The king set up a new system. His scribe, Æthelstan A, traveled with him from meeting to meeting. All the charters had a similar look. They included details like the king's regnal year (how many years he had been king), the indiction (a 15-year cycle), the epact (a number for calculating Easter), and the age of the moon. Historians say nothing quite like these charters had been seen before. They must have seemed very impressive and formal.

A unique feature is that three charters for religious groups asked them to sing a certain number of psalms for the king. This shows that the king or the scribe was very interested in psalmody (singing psalms).

These charters also help historians track the king's movements. They often named the place where the royal assembly was held. This is rare for this time period in England.

In 935, a new, simpler style of charter was introduced by other scribes. This happened while Æthelstan A was still working. This new style became the standard until the late 950s. Since charters were no longer written in Æthelstan A's special style after he stopped, it's likely he worked on his own.

The Style of the Charters

The quality of Latin writing improved in England in the 900s. This was especially true after about 960, when leaders of the Benedictine reform movement started using a very fancy and decorative Latin style. This style is now called the hermeneutic style. Its use goes back to King Æthelstan's time.

Æthelstan A borrowed a lot from an earlier writer named Aldhelm. He didn't copy whole sentences, but he would take a word or a few words. Then he would put them into his own sentences, making them sound like Aldhelm's works. One historian believes Æthelstan A changed the language in each charter because he loved to experiment and wanted to show off his writing skills.

This fancy style was also influenced by Irish texts from the 600s, known as Hiberno-Latin. These texts were brought to England by scholars from Europe, like Israel the Grammarian, who visited King Æthelstan's court.

Historians note that while the big revival of fancy Latin writing happened in the mid-900s, this style actually started earlier. It first appeared in the royal charters of the 920s and 930s. Æthelstan A's charters are known for their rich, wordy style. They have very literary introductions and warnings, grand language, and detailed dating sections. They also have those very long witness lists. These documents clearly aimed to be stylish and impressive.

Some scholars don't like the style, finding it too much. However, others describe Æthelstan A's style as having a "poetic quality." They see him as a very talented writer who not only changed the legal form of the charter but also wrote Latin that is "fascinating" and "complex." It seems fitting that these grand documents appeared after King Æthelstan's big victory in the north in 927.

See Also

Sources

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |