Three-drum boiler facts for kids

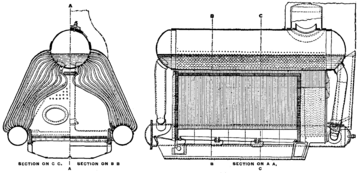

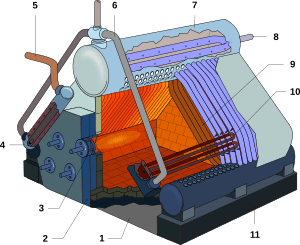

Three-drum boilers are special machines that make steam, usually to power ships. They are called "three-drum" because they have three large metal containers, or "drums," arranged in a triangle shape. One drum is at the top, called the steam drum, and two are at the bottom, called water drums.

Lots of small pipes, called water tubes, connect these drums. The furnace, where the fire burns, is in the middle of this triangle. The heat from the fire turns the water in the tubes into steam. These boilers are great for ships because they are powerful and don't take up much space. They can be heated by burning coal or oil.

How Three-Drum Boilers Were Developed

Three-drum boilers started to be developed in the late 1800s. Navies needed powerful boilers that were also small enough to fit on their ships. Older boilers, like the Babcock & Wilcox, were good but often too big. The three-drum design was lighter and more compact for the same amount of power.

Newer "small-tube" boilers used water tubes that were only about 2 inches (5 cm) wide. This was much smaller than older designs. Smaller tubes meant more heating surface for the water, which helped the boiler make steam faster. These fast-steaming boilers were sometimes called ""express" boilers".

The tubes in three-drum boilers were often almost straight up and down. This helped the water move around naturally, like a thermosyphon (where hot water rises and cooler water sinks), which also made steaming faster.

Over time, boiler makers tried to make these designs simpler. Early boilers had tubes with lots of bends, which were hard to clean. Later designs used straighter tubes that were easier to maintain.

Cleaning Boiler Tubes

Cleaning the inside of boiler tubes was a big challenge. Over time, scale (like limescale in a kettle) could build up inside the tubes. This scale made the boiler less efficient and could cause problems.

Early designs with sharp bends in their tubes, like the du Temple boiler, were almost impossible to clean properly. Later, people used special tools, like hinged rods with brushes, or even 'bullet' brushes shot through the tubes with compressed air. It was very important to make sure no brushes were left behind, as they could block a tube!

Water Flow in Boilers

For a boiler to work well, water needs to constantly move through the tubes. Hot water rises as it turns into steam, and cooler water needs to flow down to replace it. This is called circulation.

Some boilers used separate pipes called downcomers for the cooler water to flow down. However, some designs, like the Yarrow boiler, found ways for the water to circulate even within the heated tubes themselves.

Types of Three-Drum Boilers

White-Forster Boiler

The White-Forster boiler was designed to be easy to build and maintain. Its tubes had only gentle curves, which meant they could be replaced without taking out other tubes. This was very helpful for repairs on ships.

These boilers had very small tubes, making them efficient at heating water. They also had their lower water drums raised up, which created more space for the fire. This was good for burning oil, which was becoming more common on warships around 1906. The White-Forster boiler looked a lot like the later Admiralty boiler.

Normand Boiler

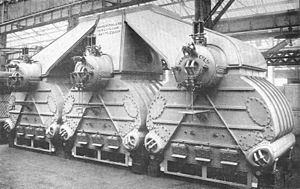

The Normand boiler was created in France and was used by many navies, including those of France, Russia, Britain, and the United States. By 1896, the British Royal Navy had more Normand boilers than any other water-tube design.

This boiler had a very large heating area because it packed so many tubes into a small space. The tubes were bent into complex shapes, but their ends entered the drums straight, which helped prevent leaks.

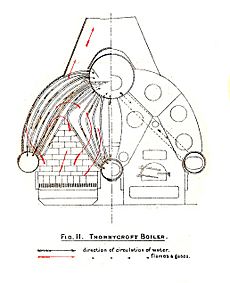

Thornycroft Boiler

The Thornycroft boiler was different because it had two separate furnace areas instead of one central one. It also used "water-walls," which are tubes placed very close together to form a solid wall around the fire. This helped protect the boiler casing from the intense heat.

This design was first used in the destroyer HMS Daring in 1893, so it became known as the 'Daring' boiler.

Thornycroft-Schulz Boiler

Later versions, like the Thornycroft-Schulz, made the outer parts of the boiler more important. They added more tubes to these sections, making them the main areas for heating. The side drums became big enough for a person to go inside for cleaning and repairs.

Yarrow Boiler

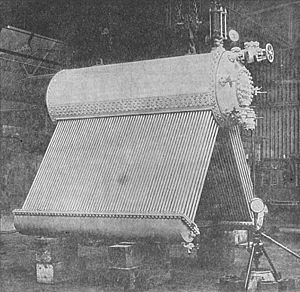

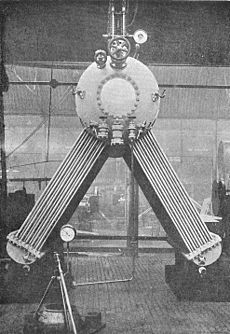

The Yarrow boiler is famous for using straight water tubes and not needing separate pipes for water to flow downwards (downcomers). All the water circulation happens within the same group of heated tubes.

Alfred Yarrow started developing his boiler in 1877. He realized that straight tubes would be much easier to make and clean.

Yarrow's Circulation Experiments

People used to think that water could only circulate if the cooler water flowed down through unheated pipes. But Alfred Yarrow did a famous experiment that proved this wrong.

He used a U-shaped tube and heated one side. As expected, the water flowed upwards on the heated side. Then, he also applied some heat to the "cooler" side. Surprisingly, the water flow actually increased! This showed that circulation could continue even if all the tubes were heated, as long as there was some difference in heating.

This meant the Yarrow boiler didn't need separate downcomers. Water flowed up through the tubes closest to the fire and down through the tubes further away, all within the same tube bank.

The British Royal Navy tested the Yarrow boiler on HMS Hornet in 1893, comparing it to a traditional boiler on its sister ship. The Yarrow boiler worked very well, and the Navy started using it, especially in smaller ships. Eventually, the Navy developed its own version, the Admiralty three-drum boiler.

Woolnough Boiler

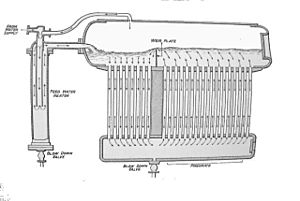

The Woolnough boiler was used by a company called Sentinel for their larger railcars and steam locomotives. It looked similar to other three-drum designs with almost straight tubes.

A special feature of the Woolnough boiler was a firebrick wall inside the furnace. The hot gases from the fire would pass through one set of tubes, then travel along an outer casing, and then come back through a second set of tubes. This meant the gases passed through the tubes twice, making the boiler very efficient.

Sentinel used this boiler on some unique locomotives, including four powerful articulated locomotives built in 1934. These locomotives ran at a very high pressure of 550 psi (3.8 MPa), much higher than typical locomotives of the time.

Admiralty Boiler

The Admiralty three-drum boiler was an improved version of the Yarrow boiler, developed for the Royal Navy between World War I and World War II. These boilers were first used in the A class destroyers in 1927.

This design was similar to later Yarrow boilers, but its tubes were slightly bent at the ends. They were arranged in two groups with a gap in between. Superheaters (which make the steam even hotter) were placed inside this gap. This helped the boiler work better by making the water circulate more effectively.

Improving Water Flow

Early Admiralty boilers had problems with water circulation. Engineers fixed this by changing how the feedwater (cold water entering the boiler) was added. They also put special plates inside the steam drum to guide the water flow. This helped steam bubbles escape and made sure the water circulated smoothly.

Better Superheaters

At first, the superheaters didn't work as well as hoped. But engineers from Babcock & Wilcox improved them by making the steam flow faster through the superheater tubes. This prevented the tubes from getting too hot or breaking. Newer boilers could make steam much hotter, which made the ships more efficient.

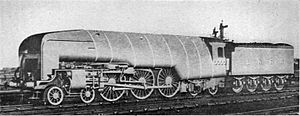

Engine 10000 Boiler

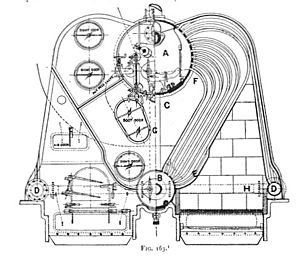

The only large three-drum boiler used in a railway locomotive was on Nigel Gresley's experimental Engine 10000. This locomotive was built in 1924 for the LNER company in Britain.

Gresley wanted to try using higher pressures and more advanced engine designs, similar to what was being done in marine engines. The boiler on Engine 10000 was a special version of the Yarrow design. It was like two Yarrow boilers joined together, end-to-end.

This boiler worked at a very high pressure of 450 pounds per square inch (31 bar), much higher than other locomotives at the time. It was fired with coal from one end. Because of how the hot gases flowed, the water circulated differently than in a typical Yarrow boiler, more like the Woolnough design.

Images for kids