American Indian boarding schools in Wisconsin facts for kids

There were ten American Indian Boarding Schools in Wisconsin that operated in the 19th and 20th centuries. These schools aimed to change Native American children to fit into European-American culture. This was often done by force and sometimes involved abuse. Churches, the government, and private groups ran these boarding schools.

Contents

Hayward Indian Boarding School

The Hayward Indian Boarding School was in Hayward, Wisconsin. It opened on September 1, 1901. Most students were from the Lac Courte Oreille Reservation, who are also known as the Chippewa (Ojibwe). The government ran and paid for this school for over 30 years, based on Christian values.

In 1923, the school had 1,309 people living there. This included 251 boys under 20, 232 girls under 17, 386 men 20 and older, and 440 women 17 and older.

Robert Laird McCormick, who owned the North Wisconsin Lumber Company, was important to the school. He pushed for the school to be built in Hayward. The school closed in 1934 during the Great Depression. It closed because it didn't have enough money, staff, or space.

| Minors | Adults | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 251 | 386 | 637 |

| Female | 232 | 440 | 672 |

| Total | 483 | 826 | 1309 |

Life at the School

The school often didn't have enough money, was too crowded, and didn't have enough staff. Many students got sick because of too many people, poor cleaning, dirty water, uneven heating, and bad air systems. The school's hospital could only treat eleven patients at a time. It was the only hospital for miles and served over a thousand people on the reservation. Many patients died there because of the limited care.

Daily Routines

At the Hayward Indian Boarding School, students were forced to adopt a Christian way of life. They had to give up their own beliefs and learn Christian ideas. Staff cut the students' hair and changed their names to English ones. Students lived by a strict military-like schedule, wearing uniforms and following bells. They also marched and drilled every day.

The people running the school believed these rules would make students change faster. The school aimed to teach students skilled trades and Christian beliefs. Few students graduated because of poor schoolwork. Many students had never used common American things like silverware before. Besides learning American culture, students could play sports like basketball, baseball, and football. However, these activities stopped in the 1920s due to lack of money.

Oneida Boarding School

The Oneida Boarding School was on the Oneida Reservation in Oneida, Wisconsin. It operated from 1893 to 1918. In 1887, the U.S. government planned to build a school there. This was to encourage the Oneida Nation to accept dividing their land under the Dawes General Allotment Act. The school opened on March 27, 1893. By 1899, it had 131 students and 5 staff members.

Children could attend this school for free. The lessons focused on farming and housekeeping skills, as it was a rural area. Students were not allowed to speak their native language. Those who didn't understand English would hide to speak freely and avoid being whipped.

In 1907, Dennison Wheelock suggested turning the boarding school into a day school. Because of money problems, the school closed in 1918 when the U.S. entered World War I. Some Oneida parents protested because they wanted their children to keep getting government education.

In 1924, the Catholic Diocese of Green Bay bought the school. They reopened it as the Guardian Angel Boarding School for boys and girls. It closed in 1954 and became the Sacred Heart Seminary for training Catholic priests. The seminary ran for 20 years.

In 1976, after the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act passed, the Oneida Nation leased the space from the diocese. They opened their own education office there. In 1984, the Oneida bought the school site and renamed it the Norbert Hill Center.

School Leaders

Charles F. Pierce was the first superintendent of the Oneida Government Boarding school. He was sent by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1892 to oversee building the school. He served from 1893 to 1899. His wife also helped develop the school as a teacher-administrator. She supervised five teachers. Other jobs at the school included matron, seamstress, cook, farmer, and nurse.

After Pierce, Joseph C. Hart became the Indian Agent for the Oneida in 1898 and superintendent in 1900. His time as superintendent involved many investigations due to problems and suspicions.

Hart kept detailed reports about daily life at the school. Students attended for ten months a year. Boys learned farming skills like gardening and caring for animals. Girls learned domestic tasks like cooking, cleaning, and other household chores.

The Outing System

The "Outing System" was part of the boarding school system. Native American students were encouraged to work in white families' homes during the summer. This idea started at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. It aimed to help students fit into European-American culture even more. It also stopped them from practicing their own culture when not in school.

The work they did for white families was often farming-related, like tending crops and animals. The Outing System also aimed to discipline students. If students broke rules set by their host families, they could be severely punished. This strict life forced students to quickly adapt and cut them off from their own cultures.

Some students lived with white families while attending school. In winter, Oneida children could attend public school. They would stay with a white family for a place to live and food. In return, the children worked for the family before and after school.

Saint Joseph's Indian Industrial School

The Menominee Indian boarding school, also called Saint Joseph's Indian Industrial School, was built on the Menominee Indian reservation in Keshena, Wisconsin in 1883. It operated until 1952. In 1899, the school had 170 students and 5 staff. Many students were from the Menominee Nation, but the school challenged their culture and traditions.

The school was run by the Keshena Indian Agency. This agency helped communicate with Native Americans. In 1932, school lands covered 440 acres out of 505 acres managed by the agency.

Religion's Role in Saint Joseph's

In the early 1800s, Catholic missionaries visited the Menominee. Many Menominee later became Catholic. By the early 1840s, a Catholic priest named Father Bonduel worked on the reservation. After he left, the Franciscan Order took over the schooling system.

The Franciscan Order and the Indian Office (Bureau of Indian Affairs) had disagreements. The Indian Office didn't want more people to become Catholic. They worried about Catholic priests influencing the reservation's culture, as most official staff were Protestant. They wanted to make sure Catholics weren't encouraging support for a "foreign Pope." Because of this, the Franciscan Order wanted to keep control over schooling. Saint Joseph's Indian Industrial School was built in 1883. The Indian Office stopped allowing priests and nuns to teach in boarding schools. They wanted schools to follow the model of the Carlisle Indian School.

History of Saint Joseph's Indian Industrial School

Early Years

When forced to live on the Menominee reservation around 1852, the Menominee tried to adapt. They found the federal officials' advice unhelpful. The Menominee were interested in the U.S. State government education system. They were willing to try farming and education if the U.S. federal government would end the harsh life on the small reservation.

By 1870, the U.S. federal government regularly funded education for tribal reservations, even without treaties requiring it. This money went to government or mission schools. Over the next ten years, issues between the Menominee Nation and U.S. officials about boarding schools often involved religion. The priest did not support the boarding schools. He threatened to remove church members who sent their children there.

In 1876, a U.S. federal government inspector visited the reservation. They suggested a manual labor boarding school in Keshena, Wisconsin. The government decided to build one. These schools combined academic lessons with farming and mechanical work. When the school first opened, the priest said he would expel church members who sent their children there. As a result, only two students attended from 1878 to 1880. The federal government told the priest he couldn't minister to Native Americans if he opposed parents sending their children to school.

To stay on the reservation, the priest stopped acting against parents. About 102 students signed up, with an average of 76 attending. The tribe approved spending six thousand dollars for a new building. These changes started a new era for Menominee schooling that lasted into the 20th century. More Menominee children attended boarding schools, mostly on the reservation in Keshena.

Middle Years

The "Browning Ruling" (1896-1902) greatly affected Saint Joseph's. It said the Office of Indian Affairs decided where Native American students could go to school. Saint Joseph's, as a mission school, also faced money problems. In 1897, a rule was added to a federal bill that stopped government funding for non-religious schools. Saint Joseph's had to accept more Native American students than it could afford.

The federal government allowed Saint Joseph's an unusual way to get money. In 1897, the school could use the Menominee logging fund. This was money the government held for the Menominee people from logging leases on their land. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs said the school needed a yearly petition with tribal signatures. This petition had to say they wanted the logging money to go to the school, not directly to tribal households.

Many Menominee tribal members refused to sign the petition. They relied on the logging money to buy goods and survive winter. They also didn't like the first wording of the petition, which suggested signers would get less money. So, the wording was changed to say all Menominee members would get less money. School leaders also tried to get signatures by refusing to bury or threatening to remove from the church those who didn't sign. Problems with this yearly petition for funding continued until Saint Joseph's closed in 1952.

Later Years

Over the years, Saint Joseph's became a popular place for most Menominee on the reservation. In 1933, Father Engelhard wrote that the school and Catholic Church had full community support. It became easier for the church to get enough signatures for the yearly petition.

In 1933, the Menominee tribe asked the federal government to merge Saint Joseph's with the government boarding school. They found it easier to work with Saint Joseph's than the Indian Agency. This merger gave the school more money, helping its financial problems. After the merger, Ralph Fredenberg (Menominee), a Catholic, became an Indian agent in 1934. He was appointed by John Collier, Commissioner for the Office of Indian Affairs.

Fredenberg wanted the Menominee to be able to support themselves financially. He also wanted to keep their unique culture. However, problems grew between Fredenberg and Saint Joseph's. Fredenberg wanted the school to focus more on job training instead of just reading and writing. He also wanted attendance to be based on how useful the classes were, not just required. In 1937, an inspection found the school hadn't done enough to follow Fredenberg's ideas. They also suggested fewer students. The school didn't follow these suggestions. In 1941, Father Engelhard was replaced by Father Benno Tushaus. But the U.S. entering World War Two caused delays in major changes at the school. The government kept pushing for changes.

In 1945, Father Benno Tushaus asked for a school bus to pick up students living far away. The Office of Indian Affairs used this chance to move these students to public schools closer to their homes. Father Benno didn't like this. Because of this and "irreconcilable differences" with the tribal government, Father Benno left the school in 1951.

When Father Belker became administrator in January 1952, he closed the school. He said there weren't enough teachers. Later, he said the Menominee no longer needed boarding schools. When boarding schools focused on making Native Americans fit into American culture, they had a clear purpose. But when the goal in the 1930s became self-sufficiency and self-determination, Belker felt the boarding school was no longer needed.

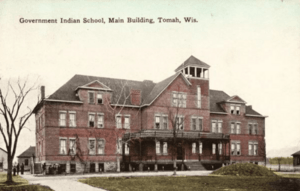

Tomah Indian Industrial School

The Tomah Indian Industrial School opened in 1893. It was a government boarding school in Wisconsin, not on a reservation. It was located along a main railroad. It educated children from the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, who were called "Winnebago" by white settlers at the time. White leaders and officials wanted this school. It was the first of its kind in Wisconsin and was known for its academic and religious teaching. Most students were Ho-Chunk, but it also served Ojibwe, Oneida, and Menominee students from Wisconsin reservations.

School Features

The school's rules were based on European-American culture. They aimed to make students "American." This meant giving students English names, teaching them English and American customs, making them attend church regularly, and teaching Christian values. The Tomah Indian Industrial School also included manual labor as part of its learning. Older students worked on nearby farms. They lived with families where they could improve their English. Subjects offered included religious practices, social life, music, sports, and military training. Classes went up to 8th grade, not including kindergarten. Few public high schools existed in the U.S. at that time. Most students taking classes above eighth grade were in private schools. Schoolwork followed the rules set by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Daily Life

In 1896, daily life at the Tomah Indian Industrial School was very strict. Boys usually did manual labor like farming, managing animals, and carpentry. Girls learned domestic duties such as sewing, cooking, and laundry.

The sewing room was where girls spent a lot of time. By the end of the school year, each girl in sewing class could make a dress for any child without help. Girls also learned long and short stitch embroidery.

All students attended church services in Tomah on Sunday afternoons. The superintendent led Sabbath school at 2 p.m., which all students and staff attended.

A Model School

Over 2,000 students attended the Tomah Indian Industrial School during its years of operation. The school was known for reducing Native American children's cultural backgrounds and making them more American. The school's goals matched the educational goals of white leaders at the time. For example, students had religious conversions, celebrated U.S. federal holidays, attended regular church services, learned patriotic and folk music, were given different names, and learned English. The U.S. Department of the Interior liked the school very much. The Tomah Indian Industrial School was seen as a model for how other schools could be developed.

List of Native American boarding schools in Wisconsin

- St. Mary's Indian Boarding School, Bad River Reservation, Odanah, run by Catholic Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration

- Bayfield Boarding School, Bayfield

- Bethany Mission, Wittenberg

- The Red Springs Indian Mission, Gresham

- Good Shepherd Industrial School, Milwaukee

- Hayward Indian Boarding School, Hayward

- St. Joseph's Industrial School, Keshena, operated by the Diocese of Green Bay

- Lac du Flambeau Government Boarding School

- Oneida Boarding School, Oneida Reservation, Oneida

- Tomah Indian Industrial School, Tomah