Anatole Broyard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anatole Broyard

|

|

|---|---|

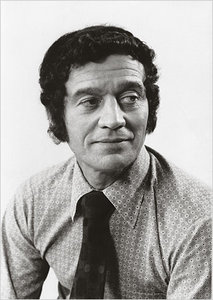

Broyard in 1971

|

|

| Born | Anatole Paul Broyard July 16, 1920 New Orleans, Louisiana, US |

| Died | October 11, 1990 (aged 70) Boston, Massachusetts, US |

| Alma mater | New School for Social Research |

| Spouse | Aida Sanchez (divorced) Alexandra (Sandy) Nelson |

| Children | 3 |

Anatole Paul Broyard (born July 16, 1920 – died October 11, 1990) was an American writer. He was also a critic and an editor for The New York Times. He wrote many reviews and articles. He also published short stories, essays, and two books while he was alive. Two more books about his life were published after he passed away.

Contents

About Anatole Broyard's Life

His Early Years

Anatole Paul Broyard was born on July 16, 1920. His family lived in New Orleans, Louisiana. They were a Black Louisiana Creole family. His father, Paul Anatole Broyard, was a carpenter. His mother was Edna Miller. Neither of his parents finished elementary school.

Anatole's family had ancestors who were free people of color before the Civil War. This meant they were not enslaved. The first Broyard in Louisiana was a French colonist in the 1700s. Anatole was the second of three children. He and his older sister, Lorraine, had light skin. Their younger sister, Shirley, had darker skin. Shirley later married Franklin Williams, a civil rights leader.

During the Great Depression, Anatole's family moved. They went from New Orleans to New York City. This was part of the Great Migration. Many African Americans moved north for work.

Anatole's daughter, Bliss Broyard, shared a story. She said her father grew up in Brooklyn. He moved there when he was six. Both white and Black kids sometimes picked on him. Black kids teased him for looking white. White kids rejected him because his family was Black. He would come home with torn clothes. His parents did not ask what happened. His mother said he kept his background a secret. He wanted to protect his own children from similar struggles.

The Broyard family lived in a diverse area of Brooklyn. Anatole saw his parents "pass" as white. This helped his father get work. The carpenters union was unfair to Black workers. By high school, Anatole became very interested in art and culture.

Starting His Career

In the 1940s, Anatole had some stories published. He started college at Brooklyn College. This was before the U.S. joined World War II. When he joined the Army, the military was segregated. Black soldiers could not be officers. Anatole was accepted as white when he joined. He finished officer training successfully. During his time in the Army, he became a captain.

After the war, Broyard continued to live as a white person. He used the GI Bill to study. He went to the New School for Social Research in Manhattan.

Life as a Writer and Critic

Broyard settled in Greenwich Village. This area was known for its bohemian artists and writers. For a while, Broyard owned a bookstore. He wrote about this time in 1979:

Eventually, I ran away to Greenwich Village, where no one had been born of a mother and father, where the people I met had sprung from their own brows, or from the pages of a bad novel... Orphans of the avant-garde, we outdistanced our history and our humanity.

Broyard did not focus on Black political causes. Sometimes, he did not tell people he was partly Black. But many people in Greenwich Village knew about his background. This was true from the early 1960s.

Writer Brent Staples said in 2003 that Broyard wanted to be a writer. He did not want to be just a "Negro writer." Historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. added that Broyard wanted to write about general human feelings. He wanted to write about love, passion, suffering, and joy. He did not want to write only about Black experiences.

In the 1940s, Broyard published stories. They appeared in magazines like Modern Writing and Discovery. He also wrote articles for Partisan Review and Commentary. Some of his stories were in books with Beat writers. But Broyard did not feel he was part of that group.

People often said Broyard was working on a novel. But he never published one. After the 1950s, he taught creative writing. He taught at The New School, New York University, and Columbia University. He also reviewed many books. For almost 15 years, Broyard wrote daily book reviews for The New York Times.

In the late 1970s, Broyard started writing short personal essays. These were for the Times. Many people thought these were his best works. They were collected in a book called Men, Women and Anti-Climaxes in 1980. In 1984, Broyard got his own column. This was in the Book Review section. He also worked as an editor there. He was seen as a "gatekeeper" in the New York literary world. His good reviews were very important for a writer's success.

His Family Life

Broyard first married Aida Sanchez. She was a Puerto Rican woman. They had a daughter named Gala. They divorced after Broyard returned from World War II.

In 1961, when he was 40, Broyard married again. His second wife was Alexandra (Sandy) Nelson. She was a modern dancer. She was also of Norwegian-American background. They had two children: Todd, born in 1964, and Bliss, born in 1966. The Broyards raised their children as white. They lived in suburban Connecticut. When their children were older, Sandy asked Broyard to tell them about his family's background. But he never did.

Before he died, Broyard said he missed his friend Milton Klonsky. They used to talk every day. After Milton died, Broyard felt "no one talked to me as an equal."

Broyard's first wife and daughter were not mentioned in his The New York Times obituary. Sandy told their children about their father's ancestry before he passed away.

His Passing

Anatole Broyard died on October 11, 1990. He passed away from prostate cancer. He was at the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

His African-American Ancestry Revealed

In 1996, six years after Broyard's death, Henry Louis Gates wrote about him. The article was called "White Like Me" in The New Yorker. Gates felt Broyard had hidden his African-American background. He thought Broyard had "passed" as white. But Gates also understood Broyard's desire to be a successful writer. He wrote:

When those of mixed ancestry—and the majority of blacks are of mixed ancestry—disappear into the white majority, they are traditionally accused of running from their "blackness." Yet why isn't the alternative a matter of running to their "whiteness"?

In 2007, Broyard's daughter, Bliss, wrote a book. It was called One Drop: My Father's Hidden Life: A Story of Race and Family Secrets. The title refers to the "one-drop rule." This rule was used in many southern states in the early 1900s. It said that anyone with any known Black ancestry was considered Black.

Anatole Broyard's Books

- 1954, "What the Cystoscope Said", Discovery magazine. This is one of his most famous short stories. It was also in Intoxicated by My Illness (1992).

Published Books

- 1974, Aroused By Books, a collection of his reviews.

- 1980, Men, Women and Other Anticlimaxes, a collection of his essays.

- 1992, Intoxicated by My Illness: and Other Writings on Life and Death (published after his death).

- 1993, Kafka Was The Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir (published after his death).

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |