André Gide facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

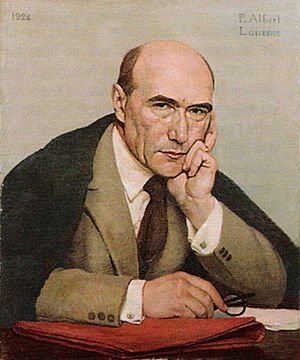

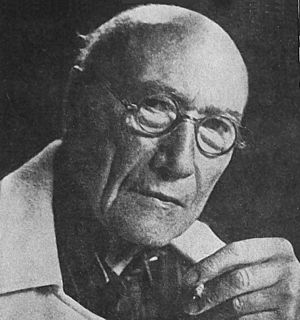

André Gide

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | André Paul Guillaume Gide 22 November 1869 Paris, France |

| Died | 19 February 1951 (aged 81) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Cuverville, Cuverville, Seine-Maritime |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Lycée Henri-IV |

| Notable works | The Immoralist Strait Is the Gate Les caves du Vatican (The Vatican Cellars) The Pastoral Symphony The Counterfeiters The Fruits of the Earth |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1947 |

| Spouse |

Madeleine Rondeaux

(m. 1895; died 1938) |

| Children | Catherine Gide |

| Signature | |

|

|

André Paul Guillaume Gide (22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a famous French writer who won the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. His career was long and varied, starting in a style called Symbolism and later including critiques of imperialism (when powerful countries control weaker ones).

Gide wrote more than 50 books. He was known for his novels and his autobiographical works, which are stories about his own life. A major theme in his writing is the search for freedom and honesty. He explored the conflict between strict societal rules and the need to be true to oneself. His work encourages readers to think for themselves and to live with intellectual honesty.

Contents

Early Life and Career

André Gide was born in Paris, France, on November 22, 1869. His family was middle-class and Protestant. His father, Jean Paul Guillaume Gide, was a law professor who passed away when André was just 11 years old. His mother was Juliette Maria Rondeaux.

Gide grew up mostly in Normandy and felt quite isolated. He started writing at a young age. He published his first novel, The Notebooks of André Walter, in 1891 when he was 21.

In the 1890s, Gide traveled to North Africa. These trips were very important to him. They helped him better understand himself and gave him new ideas for his writing.

The Middle Years

In 1895, Gide married his cousin, Madeleine Rondeaux. A year later, he was elected mayor of La Roque-Baignard, a small community in Normandy.

In 1908, Gide helped start an important literary magazine called the Nouvelle Revue Française (The New French Review). This magazine became very influential in French literature.

During World War I, Gide spent time in England. He became friends with the artist William Rothenstein. Rothenstein later wrote about Gide's visit, describing him as a deep thinker with a unique style. He said Gide had a "half satanic, half monk-like mien" and that "the heart of man held no secrets for Gide."

In the 1920s, Gide became a role model for younger writers like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1924, he published a book called Corydon, which discussed his personal beliefs. The book was very controversial at the time and was condemned by many people. Gide, however, felt it was one of his most important works.

In 1923, Gide had a daughter named Catherine. She was his only child.

After 1925, Gide began to speak out for better treatment of criminals. His wife, Madeleine, died in 1938. He wrote about their life together in a memoir called Et nunc manet in te.

Travels in Africa

From 1926 to 1927, Gide traveled through French colonies in Africa, including the Congo and Chad. He kept a detailed journal of his experiences, which he published as two books: Travels in the Congo and Return from Chad.

In these books, Gide criticized how French companies were treating the African people. He described how local workers were forced to collect rubber in the forest under terrible conditions, which he compared to slavery. His writing helped to expose the problems of colonialism and inspired many people in France to call for reform.

Political Views

Thoughts on Communism

During the 1930s, Gide became interested in Communism. He was what is known as a "fellow traveler," meaning he supported the ideas of Communism but never officially joined the Communist Party. He was invited to visit the Soviet Union in 1936.

However, his trip left him very disappointed. He saw that people were not truly free and that the government controlled what artists could create. He wrote about his experiences in a book called Return from the U.S.S.R. In it, he criticized the lack of freedom and the pressure for everyone to conform. He wrote:

What is wanted now is compliance, conformism. What is desired and demanded is approval of all that is done in the U. S. S. R. ... the smallest protest, the least criticism, is liable to the severest penalties, and in fact is immediately stifled.

His book was not welcomed by the Soviet government or its supporters. In a follow-up book, Afterthoughts on the U.S.S.R., he was even more critical. He argued that a new ruling class had emerged in the Soviet Union that was exploiting the workers.

Later Beliefs

During World War II, Gide's views continued to evolve. He came to believe that total freedom could be destructive without tradition and discipline. He rejected Communism because he felt it broke away from the important traditions of civilization. In 1947, he said that he remained an individualist who protested against "the submersion of individual responsibility in organized authority."

Later Life and Legacy

In 1939, Gide became the first living author to have his work published in the respected Bibliothèque de la Pléiade collection.

He spent most of World War II in North Africa. In 1947, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel committee praised his "comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight."

André Gide died in Paris on February 19, 1951. In 1952, the Roman Catholic Church placed his works on its list of forbidden books because of his challenging ideas.

Gide is remembered as one of the most important writers of the 20th century. His work continues to be read and studied for its beautiful style and its deep exploration of freedom, morality, and the search for one's true self.

See Also

In Spanish: André Gide para niños

In Spanish: André Gide para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |