Antankarana facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| over 50,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (syncretic with traditional beliefs) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Malagasy groups, Austronesian peoples, Bantu peoples |

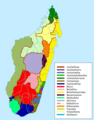

The Antankarana people live in the northern part of Madagascar, near a city called Antsiranana. Their name means "people of the tsingy." Tsingy are special limestone rock formations found in their homeland. You can see these unique rocks at the Ankarana Reserve. As of 2013, there are more than 50,000 Antankarana people in Madagascar.

The Antankarana group separated from the Sakalava people in the early 1600s. This happened because of a disagreement over who should be king. They moved to the northern tip of the island and became the main group there. When they faced conflicts with the Sakalava or the Kingdom of Imerina (another powerful kingdom), they would hide in the natural caves and rock shelters of the Ankarana Reserve. This place became very important and sacred to them, and they even named themselves after it.

In the 1800s, an Antankarana king made a deal with French visitors from Réunion. The French helped them fight against the Merina people. In return, the French gained control of some small islands near Madagascar. The Antankarana also helped the French take over Madagascar in 1896. Today, the Antankarana are one of the few groups in Madagascar that still honor a single king. They perform old ceremonies to show respect for his special role passed down from his ancestors.

The Antankarana share many traditions with their Sakalava neighbors. They practice tromba, which is when ancestral spirits are believed to possess someone. They also believe in nature spirits. They follow many fady, which are traditional rules or taboos. Some of these rules help protect wildlife and nature. In the past, the Antankarana mainly fished and raised animals. Now, many also farm or work in jobs like teaching or trade.

Contents

History of the Antankarana People

The Antankarana were originally part of the Sakalava royal family, known as the Zafin'i'fotsy (children of silver). In the 1500s, they had a disagreement with another branch, the Zafin'i'mena (children of gold). The Zafin'i'mena won the right to be kings. So, the Zafin'i'fotsy left the Sakalava area and settled north of their land.

The first Antankarana king, Kozobe (1614–1639), claimed a large area in the north. He divided it among his five sons. However, the Sakalava, led by Prince Andriamandisoarivo, soon started taking over parts of the Antankarana land. Many Antankarana nobles were killed or gave up. But some, like Andriamanpangy, fought back.

His son, Andriantsirotso (1692–1710), founded the Antankarana kingdom. He led his people further north into the Ankarana Reserve area. He became king of the north, and the people already living there joined him. They all united under the name Antankarana, meaning "people of the Ankarana rocks." The Sakalava continued to fight them, but the Antankarana hid in the natural rock shelters and caves of Ankarana.

Later, they had to seek safety in a town called Maroantsetra. Andriantsirotso was able to push back the Sakalava with help from a relative. During this time, Andriantsirotso set up the kingdom's rules. He organized the military, created an administration, and developed economic rules. He also introduced customs that strengthened their social order. One tradition he started was tying a mat to two special trees outside the king's house. This showed it was a royal home and symbolized the kingdom's unity.

Challenges from the Merina Kingdom

From its beginning, the Antankarana Kingdom was led by kings from Andriantsirotso's family. These included Lamboeny (1710–1790), Tehimbola (1790–1802), Boanahajy (1802–1809), and Tsialana I (1809–1822). In the early 1800s, the Kingdom of Imerina grew very powerful. They started military campaigns to control coastal areas. The Merina set up checkpoints to tax Antankarana traders, gaining economic control. Soon, Merina officials were governing Antankarana land.

King Tsialana I was forced to accept Merina rule. From 1835 to 1837, his son, King Tsimiaro I (1822–1882), tried many times to remove the Merina. He was not successful. The Merina fought back, forcing Tsimiaro to lead his people to hide in the Ankarana rocks in 1838. They lived there for over a year.

During this time, one of his own people betrayed the king, and Merina soldiers surrounded them. Stories say the king prayed for help and promised that if they survived, the Antankarana would become Muslim. Many people were shot, but the king and most of his followers escaped to Nosy Mitsio island. There, they converted to Islam. Many others drowned trying to cross. The place where they crossed, Ambavan'ankarana, is now a sacred site. People visit it to remember the escape.

French Alliance and Modern Times

In 1838-1839, the Sakalava king made a deal with the King of Zanzibar. This deal would have given Zanzibar control over the Sakalava and Antankarana kingdoms. However, King Tsimiaro never knew about this, and it did not change how things were run. While in exile on Nosy Mitsio, Tsimiaro traveled to Réunion. On April 5, 1841, he signed a treaty with the French. This treaty promised French protection for the Antankarana. In return, the French gained rights to the islands of Nosy Mitsio, Nosy Faly, Nosy Be, and Nosy Komba.

The French eventually helped push back the Merina. This allowed King Tsimiaro to move the capital back to Ambatoharaña. However, it took over 40 years for all the Antankarana to return to the mainland. When Tsimiaro died, he was buried in the Ankarana cave where he had hidden from the Merina. Other nobles are mostly buried in the Islamic cemetery near Ambatoharaña.

When France recognized Madagascar's independence in 1862, they kept their claim over the Antankarana and Sakalava areas. Tsimiaro was followed by his son, Tsialana II (1883–1924). He was born on Nosy Mitsio in 1843. Tsialana II worked closely with the French during their first military campaign against the Merina (1883–1885). He also helped them during the successful campaign of 1895. This led to French control of the island and the end of the Merina monarchy. His son, Abdourahaman, fought for the French in World War I. Later kings included Lamboeny II (1925–1938), Tsialana III (1948–1959), and Tsimiharo II (1959–1982).

After Madagascar became independent from France in 1960, the government mostly left the kings alone. This changed when Albert Zafy (1991–1996) became president. He was an Antankarana noble himself. Zafy tried to reduce the power of King Tsimiaro III. The king responded by "declaring war" on the president. This conflict ended when Didier Ratsiraka became president. He went back to not interfering with local traditions. King Tsimiaro III was thought to be removed in 2004 due to accusations, and Lamboeny III was chosen. However, conflicts between them have kept Tsimiaro III as the actual King of the Antakarana. He still leads traditional royal ceremonies and represents the Antakarana kingdom.

Antankarana Society and Culture

The Antankarana people live in the northernmost part of Madagascar. Their territory starts at Antsiranana and goes down the west coast, including Nosy Mitsio island. It is bordered by the Bemarivo River to the east and extends south to Tetezambato village.

Even though they follow national laws, the Antankarana also respect their king (Ampanjaka). He is a living descendant of a royal family that goes back almost 400 years. Every five years, the king's authority is celebrated in a ceremony called tsangantsainy in Ambatoharaña village. This ceremony includes a trip to Nosy Mitsio. This trip remembers the Antankarana people who fled to the island in the 1830s to escape the Merina army. They also visit the tombs of their ancestors who died there.

The king is chosen by a group of older royal family members. He leads joro (ancestral prayers) at ceremonies to ask for blessings from their ancestors. Another important person is the Ndriambavibe. This is a noble woman chosen by the community. She has a leadership role that is as important as the king's. The Antankarana are known for being one of the few groups in Madagascar that still strongly honors their king's ancestral power through these old rituals.

Family Life

Antankarana homes are usually built on stilts above the ground. When young men want to start a family, they often build their own houses using wood and thatch from the area. After getting married, a young woman moves into her husband's house. She manages the home and helps with planting and harvesting rice. The husband is responsible for earning money and farming the family's land. Friends and family usually give furniture and other important items as wedding gifts. It is common for people in Antankarana society to divorce and remarry.

Social Classes

Like in other parts of Madagascar, Antankarana society traditionally had three groups: nobles, commoners, and slaves. Slavery was ended by the French, but families often still remember their old connections. In traditional villages, descendants of nobles live on the northern side, and commoners live on the southern side. A central open area, often with the town hall, might separate them. If a village had a zomba (a house for royalty), it would traditionally be in this central area.

People from different classes often marry each other among the Antankarana. Most people can find a family connection to a noble. In the past, commoners were further divided into groups called karazana (types of people). These groups were based on their jobs or how they earned a living.

Religious Beliefs

Most Antankarana people identify as Muslim to some extent. Once a year, Muslims from northern and western Madagascar gather in Ambatoharaña village. They visit the tombs of Muslim kings buried there. The Islam practiced by the Antankarana mixes traditional ancestor worship and local customs with Muslim holidays and culture. Very few Antankarana practice a strict, traditional form of Islam.

Antankarana Culture and Traditions

Antankarana culture is very similar to that of their Sakalava neighbors. Their rituals are alike, and they honor many of the same ancestors. Both groups follow many of the same fady, which are traditional rules. Because of this, it can sometimes be hard to tell the two groups apart. They have friendly relations.

A unique Antankarana custom is the tsangatsaine. In this ritual, two trees growing in front of a noble family's house are tied together. This symbolizes the community's unity and the connection between the past and present, and the living and the dead. Like many other coastal groups, the Antankarana practice tromba. This is a spirit possession ritual used to communicate with ancestors. The royal ancestral spirits that possess tromba mediums are almost always of Sakalava origin. Many people believe that the spirits of the dead often live in crocodiles. Because of this, it is often fady for the Antankarana to kill crocodiles. The Antankarana also believe in tsiny, which are nature spirits.

Rice is the main part of every meal. It is often eaten with fish broth, greens, beans, or squash. Manioc (cassava) and green bananas are common foods when other preferred foods are too expensive or not in season. The Antankarana were historically herders, but now most are farmers. They still keep cattle for milk. Cattle are also seen as a sign of wealth. Giving away many cattle shows generosity, and sacrificing many to ancestors shows loyalty. Sacrificing zebu (a type of cattle) is a common part of many major rituals and celebrations. These include Muslim holidays and life events like marriage, death, and birth.

The traditional martial art of Madagascar, moraingy, and large dance parties (baly) are very popular among Antankarana youth. Young people are often more interested in Western culture than in older traditions.

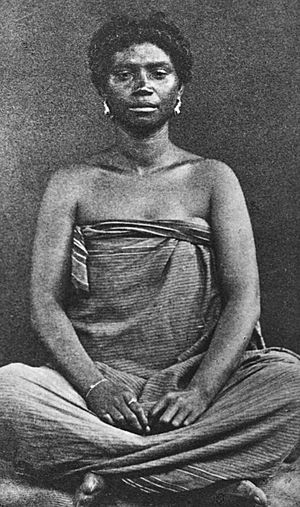

In the past, clothing was made from woven raffia. The raffia fibers were combed into strands and knotted together to make cords. These cords were then woven into panels, which were sewn together to create prayer rugs and clothes. Both women and men traditionally wore long raffia smocks.

Fady (Traditional Rules)

Many fady protect natural areas, especially the Ankarana massif. It is forbidden to cut too many mangrove trees for wood or to start bush fires. It is also forbidden to use fishing nets with holes smaller than 15 millimeters. This rule helps prevent catching young fish. Certain animals are protected by fady that forbid hunting them, such as sharks, rays, and crocodiles.

Many fady also control how men and women interact. For example, it is forbidden for a girl to wash her own brother's clothes. Some traditional communities follow a fady against medical injections, surgery, or modern medicines. This is because these things were first widely used by the Merina, their historical enemies. Instead, tromba ceremonies and traditional herbal remedies are often used for healing. These rules are strongest in the center of Antankarana territory, around Ambatoharaña village. They are less strict in villages on the edges of the region.

Funeral Customs

Funerals among the Antankarana are often joyful events. For villagers living near the sea, it is common for the family to carry the coffin of a loved one and run into the sea.

Dance and Music

At royal ceremonies, a traditional dance called the rabiky is often performed.

Language of the Antankarana

The Antankarana speak a dialect of the Malagasy language. This language comes from the Malayo-Polynesian language group. It is related to the Barito languages spoken in southern Borneo.

Antankarana Economy

In the past, the Antankarana were mainly fishermen and zebu herders. However, in recent years, most have become farmers. Sea fishing is done in two-person canoes made from a single hollowed-out log. Antankarana fishermen used these canoes to hunt whales, turtles, and fish. They also used nets to fish in rivers, catching eels, fish, crayfish, and other food. Making salt was also an important economic activity in the past. Historically, the Antankarana traded with European sailors, exchanging tortoiseshell for guns.

Today, most Antankarana still work in these traditional areas. Shrimp fishing is very profitable, and sugarcane farming is growing. However, many Antankarana now work as wage laborers. More educated community members, especially from the noble class, work in salaried jobs. These include government officials, teachers, and various other trades. The SIRAMA national sugar company factories are in Antankarana territory and employ many people. However, relatively few Antankarana work there, as their average living standard is high enough for them to find better opportunities.

The largest city in the Antankarana homeland is Antsiranana (formerly Diego-Suarez). Ambilobe, where the current king lives, is the closest major city to Ambatoharaña, the traditional center of Antankarana royal power.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Antankarana para niños

In Spanish: Antankarana para niños