Anti-literacy laws in the United States facts for kids

Anti-literacy laws were rules in many parts of the United States that made it illegal to teach enslaved people or even free Black people how to read or write. These laws were common in states where slavery was allowed, both before and during the American Civil War.

One reason for these laws was the fear that enslaved people who could read and write might create fake papers to escape to a free state. Many enslaved people did gain freedom this way. Another big reason was the fear of rebellions. Leaders like David Walker wrote books encouraging enslaved people to fight for their freedom. The Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831 also made slaveholders more afraid.

It is important to know that the United States is the only country known to have had these kinds of laws against learning.

Laws Against Learning in the States

Between 1740 and 1834, many states passed laws against teaching Black people to read and write. These states included Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. South Carolina was the first to pass such a law in 1739. It said that teaching enslaved people to read or write could lead to a large fine and time in prison.

Here are some important laws against Black people learning:

- 1829, Georgia: It became illegal to teach Black people to read. The punishment was a fine and prison time.

- 1830, Louisiana and North Carolina: Laws were passed to punish anyone teaching Black people to read. Punishments included fines, prison, or physical harm.

- 1832, Alabama and Virginia: These states made it illegal for white people to teach Black people to read or write. The punishments were fines and physical harm.

- 1833, Georgia: This state made it illegal for Black people to have jobs that involved reading or writing. It also made teaching Black people illegal, with fines and physical harm as punishment.

- 1847, Missouri: This law made it illegal to gather or teach enslaved people to read or write.

In Mississippi, a white person could go to prison for up to a year for teaching an enslaved person to read.

A law in Virginia in the 1800s said that any meeting of Black people for learning to read or write was against the law. Officers could enter these places, arrest Black people, and order them to be physically punished.

In North Carolina, Black people who broke this law faced physical punishment, while white people received fines or jail time.

Bishop William Henry Heard of the AME Church remembered his childhood as an enslaved person in Georgia. He said that any enslaved person caught writing faced severe physical harm. Other formerly enslaved people also remembered harsh punishments for reading and writing.

Rules about Black students' education were not only in the South. In the North, teaching Black people was not illegal. However, many Northern states, counties, and cities did not allow Black students in public schools. The few schools for Black students were often started with money from groups like the Quakers and other kind people.

In 1831, there was an attempt to open a college for Black students in New Haven. But people in the area strongly opposed it, and the project was quickly stopped. Private schools in New Hampshire and Connecticut that tried to teach Black and white students together were attacked and destroyed by angry groups of people.

People Who Fought Back Against the Laws

Teachers and enslaved people in the South found ways to get around and challenge these unfair laws. For example, John Berry Meachum moved his school from St. Louis, Missouri when that state passed an anti-literacy law in 1847. He reopened his school on a steamship on the Mississippi River. This boat was outside the reach of Missouri state law. This new school was called the Floating Freedom School.

After being arrested and serving a month in prison for teaching free Black children in Norfolk, Virginia, Margaret Crittendon Douglass wrote a book about her experience. Her book helped bring national attention to these anti-literacy laws. Frederick Douglass taught himself to read while he was enslaved, showing incredible determination.

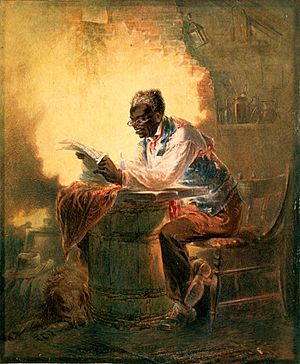

Even with all the dangers, enslaved people saw reading and writing as a way to improve their lives and gain freedom. They secretly learned from and taught each other. One historian found that 20% of enslaved people who ran away in Kentucky before the Civil War could read, and 10% could write.

Clever enslaved children would trade things like marbles or oranges to white children for reading lessons. Adults also learned from other adults, both Black and white. One enslaved man, Lucius Henry Holsey, built a small library of five books by selling rags. These books included two spelling books, a dictionary, a famous poem called Paradise Lost, and the Bible. He slowly taught himself to read by memorizing single words from these books.

Historian John Hope Franklin noted that even with these laws, schools for enslaved Black students existed throughout the South. These included schools in Georgia, the Carolinas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Florida, Tennessee, and Virginia. In 1838, free Black people in Virginia asked the state if they could send their children to school outside Virginia to avoid the anti-literacy law. Their request was denied.

Sometimes, slaveholders ignored the laws. They might look the other way when their children played school and taught their enslaved playmates to read and write. Some slaveholders even saw a benefit in having enslaved people who could read. They could help with business deals and keep records. Others believed that enslaved people should be able to read the Bible.

In Norfolk, Virginia, the anti-literacy law was not removed until after the American Civil War, in 1867. This happened because Black residents asked the federal government to end it.