Arai Hakuseki facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arai Hakuseki

|

|

|---|---|

Arai Hakuseki

|

|

| Born | March 24, 1657 Edo |

| Died | June 29, 1725 Edo |

| Occupation | Neo-confucian scholar, academic, administrator, writer |

| Subject | Japanese history, literature |

Arai Hakuseki (新井 白石, March 24, 1657 – June 29, 1725) was a very smart and important person in Japan during the middle of the Edo period. He was a Confucianist scholar, which means he studied the teachings of Confucius. He also worked as a government official, a writer, and a politician. He was a trusted advisor to the Japanese leader, the shōgun Tokugawa Ienobu. His real name was Kinmi or Kimiyoshi, but he was known by his pen name, Hakuseki.

Contents

Arai Hakuseki's Life Story

Hakuseki was born in Edo (which is now Tokyo) in 1657. From a very young age, he showed signs of being extremely intelligent. One story says that when he was just three years old, Hakuseki copied a whole book written in Kanji characters.

He was born in the same year as the Great Fire of Meireki, a huge fire in Edo. Because he was also known for being hot-tempered, people lovingly called him Hi no Ko (火の子), meaning "child of fire." This was because his brow would crease, looking like the Japanese character for fire (火).

Hakuseki first worked for a powerful lord named Hotta Masatoshi. But after Masatoshi was killed, his family lost much of their wealth. Hakuseki decided to leave and became a rōnin, which was a samurai without a master. He then studied under a famous Confucian teacher named Kinoshita Jun'an.

Serving the Shogun

In 1693, Hakuseki was asked to work for the Tokugawa shogunate. This was the government led by the shōgun. He became a key advisor, almost like a "brain," for the shōgun Tokugawa Ienobu. He became the most important Confucian scholar advising both Ienobu and the next shōgun, Tokugawa Ietsugu.

After Ienobu died, some of Hakuseki's ideas were still used. However, when the 6th shōgun, Tokugawa Ietsugu, passed away and Tokugawa Yoshimune became shōgun, Hakuseki left his government job. He then focused on writing many books about Japanese history and Western countries.

He was first buried in Hoonji temple in Asakusa. Later, his grave was moved to Kotokuji temple in Nakano, Tokyo.

Economic Changes

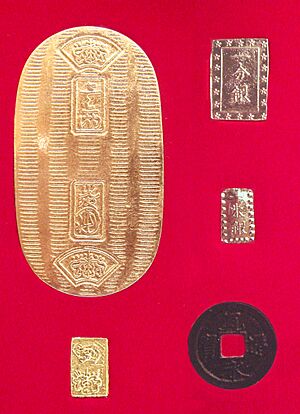

Hakuseki helped create new economic plans to make the shogunate stronger. These plans were called Shōtoku no chi. He helped control rising prices by making new, better-quality money.

He also realized that Japan was losing a lot of its gold and silver. About 25% of Japan's gold and 75% of its silver had been used to trade with other countries. To stop this, he introduced a new trade rule called Kaihaku Goshi Shinrei. This rule said that instead of precious metals, Japan should trade goods like silk, porcelain, and dried seafood with Chinese and Dutch merchants. This helped protect Japan's valuable resources.

Hakuseki also made the ceremonies for welcoming ambassadors from the Joseon dynasty (Korea) simpler. This was a big change, and not everyone agreed with it.

Government Ideas

Hakuseki believed that both the emperor and the shōgun had a special right to rule, similar to a "divine right." He argued that the shōgun was under the emperor. He thought that a shōgun proved his right to rule by governing well and showing respect to the emperor.

He also traced the Tokugawa clan's family history back to the Minamoto clan. This was to show that the first Tokugawa shōgun, Ieyasu, had a rightful claim to power. To make the shōguns power even stronger and to boost Japan's image, he suggested changing the shōguns title to koku-ō, meaning "nation-king."

Important Writings

Arai Hakuseki wrote many books and papers. Here are some of his most well-known works:

- Sairan Igen (1709): This book was about different views and strange stories from other places.

- Hōka shiryaku (1711): This was a short history of money and how it was used in Japan.

- Tokushi Yoron (1712): This book shared important lessons learned from studying history.

- Seiyō Kibun (1715): This work described Western countries. Hakuseki wrote it after talking with a European missionary named Giovanni Battista Sidotti.

- Hankanfu (1894): This book listed the family trees of important feudal lords, called daimyo.

- Oritaku Shiba-no-ki: This was a diary and memoir where Hakuseki wrote about his own life and memories.

See also

In Spanish: Arai Hakuseki para niños

In Spanish: Arai Hakuseki para niños