Assam tea facts for kids

|

|

| Type: | Black |

|

|

|

| Other names: | NA |

| Origin: | Assam, India |

|

|

|

| Quick description: | Brisk and malty with a bright colour. |

|

|

|

Assam tea is a type of black tea. It gets its name from Assam, a region in India where it's grown. This tea comes from a special plant called Camellia sinensis var. assamica. This plant is native to Assam. Early attempts to grow Chinese tea plants there didn't work out.

Assam tea is usually grown close to sea level. It's famous for its strong, full taste, lively feel, and bright color. Many "breakfast" teas, like Irish breakfast tea, use Assam tea or blends that include it. These teas often have a malty flavor and are quite strong.

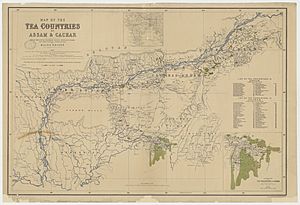

Assam is the world's largest tea-growing area. It's located on both sides of the Brahmaputra River. It borders countries like Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, and is close to China. This part of India gets a lot of rain, especially during the monsoon season. It can rain up to 250 to 300 millimeters (10 to 12 inches) per day. Daytime temperatures can reach about 36 °C (96.8 °F). This creates a very humid and hot, greenhouse-like environment. This tropical climate helps give Assam tea its special malty taste.

While Assam is known for its black teas, the region also produces smaller amounts of green and white teas. These also have their own unique qualities. Historically, Assam was the second place in the world, after southern China, where tea plants grew naturally.

The story of how the Assam tea bush came to Europe involves Robert Bruce. He was a Scottish adventurer who found the plant in 1823. Bruce reportedly saw the plant growing "wild" in Assam while he was trading there. A local person named Maniram Dewan introduced him to the Singpho chief, Bessa Gam. Bruce noticed the Singpho people making tea from the leaves of this bush. He arranged to get samples of the leaves and seeds. He wanted them to be studied by scientists.

Robert Bruce died soon after, before the plant was properly identified. It wasn't until the early 1830s that Robert's brother, Charles, sent some leaves from the Assam tea bush to the botanical gardens in Calcutta. There, the plant was finally identified as a type of tea, Camellia sinensis var assamica. It was different from the Chinese version, Camellia sinensis var. sinensis. The native Assam tea plant was first written about by historian Samuel Baidon in his 1877 book, Tea in Assam.

Contents

History of Assam Tea

In 1823, Robert Bruce was on a trading trip in Assam with the Singpho people. He learned about a plant that the Singpho and Khamti people used to make drinks and food. His brother, Charles Alexander Bruce, who was in Sadiya, sent samples of the plant to a botanist named Nathaniel Wallich. Wallich mistakenly thought it was a different plant.

More than ten years later, the Singpho plant was finally recognized. It was the same type of plant as Camellia sinensis growing in China. This happened after Francis Jenkins and Andrew Charlton responded to a request from the British East India Company's Tea Committee. They wanted to find a new source of tea outside of China.

In 1836, Charles Bruce led a team to study the plant in its natural environment near Sadiya. This team included Nathaniel Wallich, William Griffith, and John McClelland. The plant was grown in the company's experimental garden. The first batch of tea was sent to London in 1838 and sold at auction in January 1839. It sold well, but people noted it didn't smell as fragrant as Chinese tea. They thought this was because of inexperienced processing.

That same year, two companies were started to develop tea in Assam. They were the Assam Tea Association in London and the Bengal Tea Association in Kolkata. They soon joined together to form the Assam Company. Even with supporters like Maniram Dewan, the Assam Company faced challenges. British land reforms, like the Waste Lands Act, cleared land for farming. The company struggled and had to reorganize in 1847.

Assam was a hot, humid, and undeveloped area with few people. Many workers died from diseases. Even though there was cheap labor, including tea makers brought from China, and people from famine areas, conditions were tough. Despite poor results, more money came from Britain to start other tea gardens. One example was the Jorehaut Tea Company around Jorhat in the 1860s. However, by 1870, 56 out of 60 tea companies in Assam went bankrupt.

Things changed with industrial machines in the 1870s. These machines helped dry more tea leaves without them rotting in the humid climate. Heated tables for drying and steam-powered rolling machines made it possible to process more tea. This led to a need for grading the tea. The British adapted existing tea leaf grading systems to sort their products.

The Indian Tea Districts Association was created in London in 1879. It was also formed in Kolkata in 1881 as the Indian Tea Association. These groups helped organize and promote tea interests. By 1888, the amount of tea imported from India finally became more than the tea from China.

How Assam Tea is Made

Most tea estates in Assam are part of the Assam Branch of the Indian Tea Association (ABITA). This is the oldest and most important group of tea producers in India.

Steps in Tea Processing

Making tea from fresh leaves involves between two and seven steps. Adding or removing any of these steps creates a different type of tea. All these steps happen in special rooms where the temperature and humidity are controlled. This prevents the tea from spoiling.

Withering

Withering means letting the fresh green tea leaves wilt. The goal is to reduce the water in the leaves. This also helps the flavors develop. While it can be done outside, controlled withering usually happens indoors. Freshly picked leaves are spread out on trays. Hot air is blown up from underneath them. During withering, the leaves lose about 30% of their moisture. This makes them soft and ready for rolling. Also, the natural compounds in the leaf, including caffeine and flavors, start to get stronger. A short wither keeps the leaves greener and gives them a grassy taste. A longer wither makes the leaf darker and strengthens the aromatic flavors.

Fixing

Fixing, or "kill-green," stops the leaves from turning brown too much. This is done by applying heat. The longer it takes to fix the leaves, the more fragrant the tea will be. Fixing can be done by steaming, pan-firing, baking, or using heated tumblers. Steaming heats the leaves faster than pan-firing. Steamed teas often taste "green" and like vegetables. Pan-fired teas taste more toasty. This step is used for green teas and yellow teas.

Oxidation

Oxidation makes the leaves turn brown and makes their flavors stronger. As soon as leaves are picked, their cells are exposed to oxygen. The compounds inside them start to change. At this stage, special compounds like theaflavin and thearubigin begin to form. Theaflavins give tea a lively and bright taste. Thearubigins give the tea a deeper, fuller flavor.

Tea makers control how much oxidation the leaves go through to create specific flavors. Controlled oxidation usually happens in a large room. The temperature is kept at 25–30 °C (77–86 °F). The humidity stays at 60–70%. Here, withered and rolled leaves are spread on shelves. They are left to "ferment" for a set time, depending on the tea type. To stop or slow down oxidation, the leaves are moved to a heating area. They are heated and then dried.

Because of oxidation, the leaves change completely. They get a smell and taste that is very different from leaves that aren't oxidized. Less oxidized teas keep most of their green color and vegetable-like qualities. This is because fewer polyphenols are produced. A semi-oxidized leaf looks brown and makes a yellow-amber drink. In a fully oxidized tea, the leaves turn blackish-brown. The flavors in such a tea are more lively and strong.

Rolling

Rolling shapes the processed leaves into a tight form. During this step, wilted or fixed leaves are gently rolled. Depending on the style, they might be shaped to look like wires, kneaded, or rolled into tight pellets. As the leaves are rolled, essential oils and sap come out. This makes the taste even stronger. The tighter the leaves are rolled, the longer they will stay fresh.

Drying

To keep the tea free of moisture, the leaves are dried at different stages of production. Drying makes a tea's flavors better. It also makes sure the tea lasts a long time on the shelf. Drying reduces the tea's moisture content to less than 1%. To dry the leaves, they are heated or roasted at a low temperature for a controlled time. This usually happens inside a large industrial oven. If the leaves are dried too quickly, the tea can taste rough and harsh.

Aging

Some teas are aged and fermented to make them taste better. For example, some types of Chinese Pu-erh tea are fermented and aged for many years, much like wine.

Separate Time Zone

Tea gardens in Assam do not follow the Indian Standard Time (IST). IST is the time used across India and Sri Lanka. The local time in Assam's tea gardens is called "Tea Garden Time" or Sah Bagan Time. It is one hour ahead of IST. Myanmar also uses this time. This system was started by the British. They knew the sun rises earlier in this part of the country.

This system has generally helped tea garden workers be more productive. They save daylight by finishing work during the day. Working hours for tea laborers are usually from 9 a.m. (which is 8 a.m. IST) to 5 p.m. (which is 4 p.m. IST). This might change a little from one garden to another.

Famous filmmaker Jahnu Barua has been asking for a separate time zone for India's northeast region.

Where Assam Tea Grows

The tea plant is grown in the lowlands of Assam. This is different from Darjeeling and Nilgiri teas, which grow in highlands. Assam tea is grown in the valley of the Brahmaputra River. This area has clay soil that is rich in nutrients from the river's floods.

The climate in Assam has a cool, dry winter and a hot, humid rainy season. These conditions are perfect for growing tea. Because of its long growing season and plenty of rain, Assam is one of the world's most productive tea regions. Each year, Assam's tea estates produce about 680.5 million kg (1,500 million pounds) of tea.

Assam tea is usually harvested twice. The first harvest is called the "first flush" and is picked in late March. The second harvest, picked later, is called the "second flush." This "second flush" is more valued. It's also known as "tippy tea" because of the golden tips on the leaves. This second flush, tippy tea, is sweeter and has a fuller body. It is generally thought to be better than the first flush tea. The leaves of the Assam tea bush are dark green, shiny, and quite wide compared to Chinese tea plants. The bush also produces delicate white flowers.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |