Australian paralysis tick facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ixodes holocyclus |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Ixodes holocyclus before and after feeding | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Ixodida |

| Family: | Ixodidae |

| Genus: | Ixodes |

| Species: |

I. holocyclus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ixodes holocyclus Neumann, 1899

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Ixodes holocyclus, often called the Australian paralysis tick, is a very important tick found in Australia. It's known for injecting a special substance called a neurotoxin into its host, which can cause paralysis. This tick usually lives along the eastern coast of Australia, in a strip about 20 kilometers wide.

Because many people and their pets live in this area, bites from the Australian paralysis tick are quite common. These ticks like places with lots of rain, like wet forests and rainforests. Their natural homes are on animals like koalas, bandicoots, possums, and kangaroos.

Contents

- What are the different names for this tick?

- How scientists first learned about this tick

- Life cycle of the paralysis tick

- How to tell Ixodes holocyclus apart from other ticks

- Who are the common hosts for this tick?

- What eats the paralysis tick?

- When are ticks most active?

- How big are ticks?

- How ticks feed

- How much do ticks swell when they feed?

- Where do paralysis ticks live?

- What happens if a tick bites you?

- Allergic reactions to tick bites

- Tick paralysis in animals

- How to remove a tick

- Diseases ticks can carry

- See also

What are the different names for this tick?

People use many different names for Ixodes holocyclus. The most common names in Australia are Australian paralysis tick or just paralysis tick. It's best not to use names like "dog tick" or "bush tick" for Ixodes holocyclus, because these names are also used for other types of ticks in Australia.

Here are some of the names people use for the Ixodes holocyclus at different stages of its life:

| Common Name | Life Stage/Gender | What it means |

|---|---|---|

| Paralysis tick of Australia | All stages | This is the best name for Ixodes holocyclus. Other ticks around the world can also cause paralysis. |

| Scrub tick | Adult female, Adult male | In Queensland, this name is also used for another tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. |

| Bush tick | Adult female, Adult male | Across Australia, this name is also used for Haemaphysalis longicornis. |

| Dog tick | Adult female, Adult male | In New South Wales, this name is more correctly used for the Rhipicephalus sanguineus (the Brown Dog Tick). |

| Wattle tick | Adult female, Adult male | Early settlers in New South Wales used this name for the tick that caused paralysis, especially in sheep. |

| Bottle tick or blue bottle tick | Adult female | This name describes how the tick swells up with blood, looking like a bottle. The "blue" part might come from a bluish color it gets when it's partly full. |

| Shell back tick | Adult male | This name describes the male tick's hard, shell-like back. |

| Grass tick | Nymph and Larva | This term is used for smaller ticks, but any tick can be found in the grass. |

| Seed tick | Larva | This term is used for the smallest stage of the tick. |

| Shower tick | Larva | This name comes from how hundreds of tiny larvae can seem to "shower" onto a person at once. This happens because they hatch from a single cluster of eggs. |

| Scrub itch tick | Larva | Used in Queensland, this name describes the larvae that can cause a rash when many of them bite humans or animals. |

How scientists first learned about this tick

One of the first times ticks were mentioned as a problem in Australia was in 1824. A traveler named Capt William Hilton Howell wrote about a "small insect called the tick, which buries itself in the flesh, and would in the end destroy either man or beast if not removed in time."

Later, in 1899, scientists officially identified the paralysis tick. In 1921, a scientist named Dodd proved that Ixodes holocyclus was indeed causing illness in dogs. He found that it took about 5 to 6 days after a tick attached for signs of paralysis to appear.

Another scientist, Ian Clunies Ross, studied the tick's life cycle in 1924. He also showed that a special substance (a toxin) produced by the tick caused the paralysis, not a germ carried by the tick.

In 1970, a book called Australian Ticks gave a full description of many Australian ticks, including Ixodes holocyclus.

Sadly, the first confirmed human death from a tick bite in Australia was reported in 1912. It was a child who became paralyzed and couldn't breathe. In the first half of the 1900s, at least 20 human deaths were linked to the paralysis tick. Most of these victims were children under four years old.

Life cycle of the paralysis tick

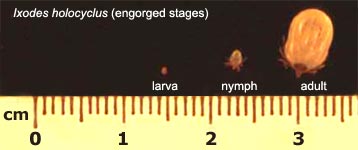

The Ixodes holocyclus tick goes through four stages in its life: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. This whole process takes about a year.

- Eggs: Adult female ticks lay thousands of tiny eggs (2,000 to 6,000!) in leaf litter or under tree bark. These eggs need warmth and humidity to hatch.

- Larvae: After 40 to 110 days, tiny, six-legged larvae hatch from the eggs. They are sometimes called "seed ticks" because they are so small. Larvae climb onto plants and wait for a host to pass by. They feed for 4 to 6 days, then drop off and change into nymphs.

- Nymphs: Nymphs have eight legs, like adults. They are very active and need a second blood meal. They feed for 4 to 7 days, then drop off and change into adult ticks.

- Adults: Adult ticks also have eight legs. Female adults need a large blood meal to lay eggs. They can feed for up to 10 days, swelling up greatly. Male adults usually look for females on the host to mate. They rarely feed on blood from the host directly, but sometimes feed from the female ticks.

To find a host, ticks "quest." This means they climb onto plants and wave their front legs, waiting for an animal or person to come close enough to grab onto. Once on a host, they might wander for up to two hours before finding a good spot to attach, often behind an ear or on the back of the head.

When a female tick is full of blood, she is called "replete." Her body can swell to 200 to 600 times her original weight!

Egg stage

Adult female ticks lay between 2,000 and 6,000 eggs in a sticky mass. They hide these eggs in moist places like leaf litter or under tree bark. Only a small number of these eggs survive to hatch into larvae. This hatching takes 40 to 110 days, depending on how warm and humid it is.

Adult female ticks lay between 2,000 and 6,000 eggs in a sticky mass. They hide these eggs in moist places like leaf litter or under tree bark. Only a small number of these eggs survive to hatch into larvae. This hatching takes 40 to 110 days, depending on how warm and humid it is.

Larva stage

![]() Larvae are tiny, just barely visible to your eye. They emerge from the eggs and climb onto plants, waiting for a host. They feed for 4 to 6 days, then drop off. Over the next 19 to 41 days, they change into nymphs. This stage can last longer in cooler temperatures. Unfed larvae can live for up to 162 days.

Larvae are tiny, just barely visible to your eye. They emerge from the eggs and climb onto plants, waiting for a host. They feed for 4 to 6 days, then drop off. Over the next 19 to 41 days, they change into nymphs. This stage can last longer in cooler temperatures. Unfed larvae can live for up to 162 days.

Nymph stage

Nymphs are very active. About 5 to 6 days after changing from a larva, they find a new host. They feed for 4 to 7 days, then drop off. After another 3 to 11 weeks, they change into adult males or females. Dry conditions can make this process longer or even kill the nymphs. Unfed nymphs can survive for up to 275 days.

Nymphs are very active. About 5 to 6 days after changing from a larva, they find a new host. They feed for 4 to 7 days, then drop off. After another 3 to 11 weeks, they change into adult males or females. Dry conditions can make this process longer or even kill the nymphs. Unfed nymphs can survive for up to 275 days.

Adult female stage

A newly grown adult female tick looks for a host. After mating with a male, or sometimes before, she feeds on blood to get the energy to lay eggs. Adult females feed for 6 to 30 days, depending on the temperature. When she is completely full, she drops off the host.

About 11 to 20 days later, the female starts laying 2,000 to 6,000 eggs over several weeks. She lays them in moist places like leaf litter. The female tick dies 1 to 2 days after she finishes laying her eggs.

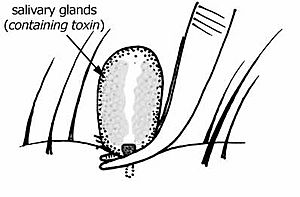

The female tick usually doesn't inject much toxin until the 3rd or 4th day of feeding. The most toxin is injected on days 5 and 6. This means a host might have a tick for a few days without showing signs of paralysis.

Adult male stage

Newly grown male ticks also look for a host. However, male ticks do not feed on the host's blood. Instead, they wander around on the host looking for unfertilized female ticks to mate with. The male tick dies after mating, though some can live longer if they feed from an engorging female.

Newly grown male ticks also look for a host. However, male ticks do not feed on the host's blood. Instead, they wander around on the host looking for unfertilized female ticks to mate with. The male tick dies after mating, though some can live longer if they feed from an engorging female.

How to tell Ixodes holocyclus apart from other ticks

There are two easy ways to recognize an Ixodes holocyclus tick:

- Its first and last pairs of legs are much darker than its two middle pairs of legs.

- The groove around its anus forms a complete, pear-shaped circle. This is why it's called holocyclus, which means 'complete circle'.

Other common ticks in Australia that might be confused with Ixodes holocyclus include the Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Brown dog tick) and Haemaphysalis longicornis (Bush tick).

Who are the common hosts for this tick?

Common hosts for the paralysis tick include bandicoots, echidnas, and possums. Many other mammals, birds, and sometimes even reptiles can also host these ticks. Native animals are usually immune to the tick's toxins because they are often bitten.

Most mammals, like calves, sheep, goats, horses, pigs, cats, dogs, rats, mice, and humans, can be bitten by the Australian Paralysis Tick. Young animals and pets like dogs and cats are most likely to get very sick from a single adult female tick. Even larvae and nymphs can cause problems. For example, 50 larvae or five nymphs can kill a small rat. Many larvae or nymphs can also cause paralysis in dogs and cats.

It's important to check your pets daily for ticks if you live in an area where ticks are common. Ticks can be hard to find on animals with long fur. By the time you can feel a tick, it might have already injected a lot of toxin.

What eats the paralysis tick?

Birds that eat insects and wasps are natural predators of the Ixodes holocyclus tick.

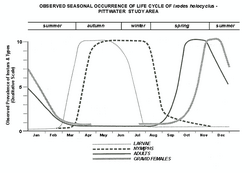

When are ticks most active?

Paralysis ticks need humid conditions to survive. Very dry or very hot (above 32°C) or very cold (below 7°C) weather can kill them quickly. A temperature of 27°C with high humidity is best for them to grow quickly.

Tick numbers in a year are often affected by how much rain fell the previous year. Warm, moist breezes from the ocean create ideal conditions, especially in spring and early summer. This is why tick paralysis in pets usually peaks from spring to mid-summer.

Generally, larvae appear from late February to May, nymphs from March to October, and adult ticks from August to February, with a peak around December. However, adult ticks can be found at any time of the year if the conditions are right, even in winter. They are only hard to find during the very hot summer months.

How big are ticks?

Comparing Unfed Ticks

| Unfed Larva (6 legs) | Unfed Nymph (8 legs) | Unfed Adult (8 legs) | Fed Adult Female (8 legs) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| 0.5 mm long, 0.4 mm wide | 1.2 mm long, 0.85 mm wide | 3.8 mm long, 2.6 mm wide | 13.2 mm long, 10.2 mm wide |

These measurements are for the tick's body only, not including its legs.

Comparing Fed Ticks Larvae, nymphs, and adult females all feed. Adult male ticks do not swell up with blood. Larvae and nymphs are not male or female.

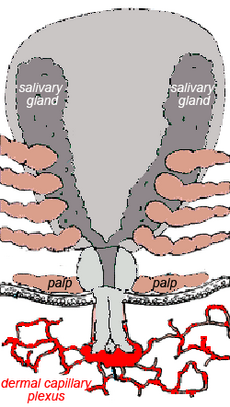

How ticks feed

Ticks must feed on blood to survive. All active stages (larvae, nymphs, and adults) need blood for energy. Adult ticks also need blood to produce sperm or eggs.

Tick feeding has two phases: a slow phase for several days, followed by a fast phase in the last 12 to 24 hours before they drop off. During the fast phase, a tick can increase its weight tenfold! This quick feeding at the end helps the tick avoid being found and removed by the host.

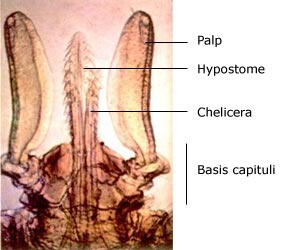

The tick's mouthparts are called the capitulum. This isn't a true head, as its brain and other organs are in its body. Ixodes holocyclus ticks do not have eyes.

- Palps: These are paired feelers that stay on the skin surface.

- Chelicerae: These are paired cutting jaws that cut a channel into the skin.

- Hypostome: This is a single feeding tube that the tick inserts into the skin. It has backward-pointing barbs that help anchor the tick firmly.

Once a tick chooses a spot, it uses its legs to lift its body. The chelicerae cut into the skin, creating a small pool of blood. The hypostome is then inserted deep into the skin. The tick then sucks blood from this pool. The tick also injects substances into the wound, like anticoagulants, which stop the blood from clotting.

Unlike some other ticks, Ixodes holocyclus does not produce a "cement" to seal itself to the skin.

How much do ticks swell when they feed?

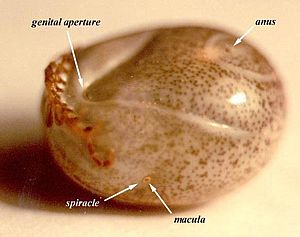

The following pictures show the adult female Ixodes holocyclus. Their color and markings change a lot as they fill with blood. The "moderately engorged" tick (the third one shown) is most often found on dogs with tick paralysis. If a dog has a fully engorged tick, it might mean the dog has some immunity to the toxin.

Adult female - No engorgement

Adult female - No engorgement

Adult female - Early engorgement

Adult female - Early engorgement

Adult female - Moderate engorgement

Adult female - Moderate engorgement

Adult female - Full engorgement

Adult female - Full engorgement

These pictures are not to scale with each other. The size of the tick's "shield" (scutum) does not change as it feeds, so you can use it to compare their relative sizes.

Where do paralysis ticks live?

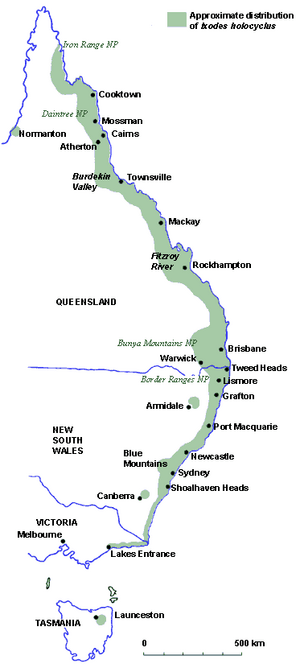

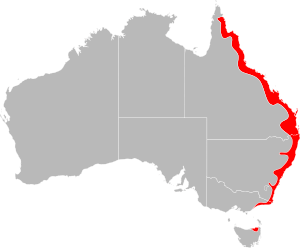

Ixodes holocyclus is found mostly along the eastern coast of Australia, from Queensland down to Victoria. In some places, it can be found more than 100 kilometers inland, especially in moist, hilly areas.

The map shows where the paralysis tick generally lives, but its range can change. There have been reports of these ticks in inland Victoria, possibly due to climate change.

These ticks need humid conditions, which is why they prefer low, leafy plants. This environment also suits their main hosts, like bandicoots, who look for food in leaf litter.

There are different ideas about whether paralysis ticks climb trees. Some say they climb to the tops of trees, while others say they stay within 50 centimeters of the ground.

What happens if a tick bites you?

The effects of an Ixodes holocyclus bite depend on who gets bitten and what stage the tick is (larva, nymph, or adult).

- Humans: People often get local irritation, numbness, or allergic reactions. Tick paralysis is possible but not common.

- Pets and farm animals: These animals are most often affected by tick paralysis. Allergic reactions are possible but not often diagnosed.

- Native animals: These animals are usually immune to the toxin. They might get anemia if they have many ticks feeding on them.

Tick bites on humans

If an adult female Ixodes holocyclus bites a human, you can expect a numb, itchy lump that lasts for several weeks.

While most tick bites on humans are not serious, some can be dangerous. These include severe allergic reactions, tick-transmitted diseases like Queensland tick typhus, and tick paralysis.

Even tiny larvae and nymphs can cause strong allergic reactions. Within 2 to 3 hours of a bite, you might see a lot of redness and swelling. Some people are so sensitive that just having a tick crawl on their hand can cause intense itching.

In southeast Queensland, many tick larvae can cause a very itchy rash called "scrub itch." If a tick bites near an eyelid, it can cause a lot of swelling in the face and neck within hours.

Systemic paralysis (paralysis affecting the whole body) is rare in humans now. This is because an adult female tick needs to stay attached for several days, and people usually find and remove them before that happens. In the past, it was more common, especially in children, and sometimes mistaken for other illnesses. Up to 1989, 20 human deaths were reported in Australia due to tick bites.

If you get an unusual black scab (called an eschar) where a tick bit you, or if you feel sick with flu-like symptoms, fever, rash, or muscle pain within a few weeks of a tick bite, see a doctor. You might have a Rickettsial infection. Early treatment with antibiotics can help. Doctors in Australia might also check for a Lyme-like disease, especially if you have a "bullseye" shaped rash.

Tick bites on domestic animals

The tick's paralyzing toxin affects many domestic animals each year. It's estimated that up to 100,000 pets and farm animals are affected, with about 10,000 pets needing veterinary care.

Allergic reactions to tick bites

All stages of Ixodes holocyclus can cause allergic reactions in humans.

Allergies to larvae

If a person is bitten by a few larvae for the first time, they might not have much of a reaction. But if they've been bitten before, they can become very sensitive. Even one larva bite can cause redness, numbness, swelling, and itching within 2 to 3 hours. If many larvae bite a sensitive person, it can lead to a severe rash called "scrub-itch."

Allergies to nymphs and adults

Bites from nymphs and adult ticks cause different reactions. Sometimes, there's little to no reaction, and a person might not even know a tick is there for days. Other times, the bite area becomes very sensitive, red, and itchy.

After the tick is removed, the itchiness might come back for weeks, and a small, firm lump usually forms. This lump can also last for many weeks. Some people also report headaches.

Meat allergy from tick bites

Interestingly, some people have developed an allergy to red meat after being bitten by a tick. This happens because mammals (like cows, sheep, and pigs) have a sugar called alpha-gal in their bodies. When a tick feeds on a mammal, it takes in alpha-gal. If that same tick then bites a human, it can transfer alpha-gal to the human.

The human immune system might see alpha-gal as foreign and create antibodies against it. This can lead to a delayed allergic reaction (3 to 6 hours after eating) when the person later eats mammalian meats (like beef, lamb, or pork). Symptoms can range from mild stomach problems to severe allergic reactions like skin rashes, swollen tongue, and a dangerous drop in blood pressure. This allergy does not affect eating chicken or fish.

A blood test can now detect alpha-gal in humans. People who have immediate allergic reactions to tick bites (due to proteins in tick saliva) might also be more likely to develop the alpha-gal meat allergy later.

Tick paralysis in animals

The toxins from Ixodes holocyclus can cause paralysis in dogs and cats along Australia's East Coast. A similar tick, Ixodes cornuatus, causes paralysis in Tasmania. The toxin is made in the tick's salivary glands and injected while it feeds.

Usually, an adult female tick needs to be attached for at least 3 days before the first signs of paralysis appear. In warm weather, signs might show up sooner. In colder weather, it can take up to two weeks. Dogs rarely show serious signs until the adult female tick has swelled to at least 4 mm wide.

If not treated, tick paralysis is often fatal. The toxin paralyzes muscles, especially:

- Leg muscles: This causes the obvious paralysis. It usually starts in the back legs, then moves to the front legs, and then to the body muscles.

- Breathing muscles: This makes breathing fast and shallow, and the animal can't cough. In severe cases, breathing becomes slow and exaggerated.

- Throat muscles: This changes the animal's voice (bark or meow) and increases the risk of food or saliva going into the lungs (aspiration pneumonia).

- Esophagus muscles: This causes drooling and regurgitation, increasing the risk of choking and aspiration pneumonia.

- Heart muscle: This can lead to heart problems and fluid in the lungs, also causing difficulty breathing.

Spring is the busiest time for tick paralysis because this is when adult ticks are most active. However, cases can happen all year round.

When a female tick attaches, she feeds slowly at first. But after about four days, she starts feeding very quickly and injects the most toxin.

Early signs in dogs and cats can be subtle, like being tired, not wanting to eat, groaning when lifted, a changed voice, noisy breathing, coughing, drooling, or enlarged pupils (in cats). Sometimes, only one leg might seem weak.

As the paralysis gets worse, the animal's back legs become weak, and they might walk as if they are "drunk." They might struggle to climb stairs. Breathing can become slow and grunting. Animals can get scared at this stage, so handle them calmly.

Eventually, the animal might not be able to stand or even lift its head. Breathing becomes slow, exaggerated, and gasping. A bad smell from the breath can mean aspiration pneumonia. Even though tick paralysis isn't thought to be painful, animals seem to be in great distress. Finally, their gums might turn bluish, and they can fall into a coma, meaning death is very near.

It's important to know that even after the tick is removed, the signs of paralysis usually get worse for up to 48 hours, especially in the first 12 to 24 hours.

The main treatment for tick paralysis is anti-tick serum. The sooner it's given, the better the chance of recovery. Even though tick paralysis develops slowly, it can be very deadly if the serum isn't given early enough.

Other treatments might include:

- Helping the animal breathe (making sure their airway is clear, giving oxygen).

- Keeping the animal calm to reduce stress.

- Keeping their body temperature normal.

- Making sure they stay hydrated.

- Protecting their eyes if their eyelids are paralyzed.

- Helping them urinate if they can't.

To prevent tick paralysis, you should check your pets daily and use tick-repelling or tick-killing products like sprays, rinses, collars, or oral medicines. Some owners even clip their pet's fur short to make ticks easier to find.

Daily checks give you a few days to find a tick. However, ticks are small and flat when they first attach, so they can be easily missed. Most ticks on dogs are found around the head, neck, and shoulders, but they can be anywhere, even between the toes.

Cats often get ticks in places they can't groom, like the back of the neck, between the shoulder blades, under the chin, or on the head. Long-haired cats that go outside are more at risk.

Matted fur or lumpy skin can also make it harder to find ticks. Some vets might shave an animal's entire coat to help find ticks.

Tick paralysis in horses

It's not known how many paralysis ticks it takes to paralyze a horse. In one study, large horses became paralyzed and couldn't stand even with only one or two ticks. Horses of any age can be affected. In that study, 26% of the horses died. Many of the surviving horses had other problems like pressure sores or pneumonia. This high death rate might be because horses are often very sick before a vet is called, or because it's hard to care for a large, paralyzed horse.

How to remove a tick

There's a lot of discussion about the best way to remove a tick. The main concerns are that the removal method might inject more harmful substances (allergens, toxins, or germs) into the host, or that the tick's mouthparts might be left behind in the skin.

The tick's salivary glands and gut contain the harmful substances. If you irritate the tick or squeeze its body, it might inject more saliva or gut contents into you. This is why you should avoid putting things like methylated spirits, nail polish remover, turpentine, or tea-tree oil on the tick, as they can irritate it. Spreading butter or oil on the tick is also not recommended.

Leaving the tick's mouthparts (often called the "head") in the skin is usually not a big problem. They usually cause a small reaction and eventually come out like a splinter. However, if you pull an Ixodes holocyclus tick out forcefully, its feeding tube (hypostome) is often damaged, meaning part of it stays in the skin.

If a tick is in a sensitive area, like an eyelid, touching it can suddenly make it painful.

Before removing a tick:

- If you have trouble removing a tick, or if you're worried about allergic reactions, it's best to get help from a doctor or nurse. Removing ticks in humans has been linked to severe allergic reactions, so it's good to have medical supplies ready.

- Tell children to ask an adult for help to remove a tick properly.

- Wear thin disposable gloves if you have them.

- Try not to touch the tick's body unnecessarily.

If you have freezing ether-spray:

- For adult ticks, it's recommended to freeze them with an ether-containing spray (used for warts, available at pharmacies).

- Once the tick is dead, you can carefully remove it without squeezing its body, or let it fall off on its own.

If you don't have freezing ether-spray:

- Use fine, curved forceps (tweezers) to grasp the tick's mouthparts as close to the skin as possible. Do NOT squeeze the tick's body. Regular household tweezers are not recommended because they can squeeze the tick.

- Grasp very firmly because the Ixodes holocyclus has a long feeding tube with backward-pointing barbs that are deeply embedded.

Other ways to grasp the tick:

- A special tick removal tool, like a tick hook, scoop, or loop. These are usually cheap and useful in tick-prone areas.

- A loop of thread can sometimes be used, but it can be tricky to place without disturbing the tick.

After removing the tick:

- Put antiseptic on the bite site. Also, clean your tick removal tool.

- Save the tick in a small airtight container with a moist piece of paper or a leaf. Label it with the date you removed it and where you think you got the tick. This can help if you get sick later. (Be careful: a full female tick will lay thousands of eggs that can escape if the container isn't sealed well!)

- Check yourself and your pets for more ticks.

Removing larval ticks:

- Larval ticks are usually found in large numbers.

- For larvae and nymphs, you can use permethrin cream (available at pharmacies).

- Another safe method is to soak in a bath with 1 cup of baking soda for 30 minutes, then scrape off the dead larvae.

Diseases ticks can carry

Hard ticks usually don't spread diseases just by carrying them from one host to another. For a disease to spread between tick stages, the germ usually needs to be able to grow inside the tick.

Bacterial diseases

Spotted fevers

Ixodes holocyclus is the main carrier of Rickettsial Spotted Fever (also called Queensland tick typhus) and Flinders Island Spotted Fever. These diseases are caused by bacteria that grow inside small blood vessels. Spotted Fever is probably more common than Lyme-like disease.

Sometimes, you can get a Rickettsial infection without a rash, just a high fever. Usually, there's a black spot (an eschar) where the tick bit, which looks like a scab with redness around it. Often, nearby lymph glands become swollen and painful. Fever starts 1 to 14 days after the tick bite, followed by a rash a few days later. The rash can look like chicken pox. Other symptoms include headache, stiff neck, nausea, vomiting, confusion, and aching muscles and joints. The illness can be more severe in adults and older people.

Spotted Fever is diagnosed with blood tests. It usually gets better on its own in about two weeks, but antibiotics can cure it faster. It's rarely fatal.

Q-fever

Ixodes holocyclus is also thought to be a possible carrier of Q-Fever.

Lyme-like disease in Australia

Lyme Disease is an illness caused by spiral-shaped bacteria called spirochaetes. The most common one is Borrelia burgdorferi. While Lyme disease is well-known in Europe and North America, it's still debated whether it can be caught in Australia. Some doctors believe it can, while others do not. If a doctor suspects Lyme-like disease, they usually treat it with antibiotics, as early treatment often leads to a full recovery.

Some studies suggest that Ixodes holocyclus cannot transmit the specific Borrelia burgdorferi strain found in the United States. However, many people strongly believe that some kind of Lyme-like bacteria causes a Lyme-like disease in Australia, and that Ixodes holocyclus carries it.

Skin rashes of Lyme-like disease. Early signs in the first four weeks after a tick bite can include a rash that slowly gets bigger over several days. It can become quite large (50 mm or more). This rash is called erythema migrans (EM). It can be hard to tell apart from an allergic reaction. Allergic rashes usually appear within 48 hours and then fade. EM usually appears after 48 hours and gets bigger over days or weeks. As it grows, EM often looks like a "target" or "bullseye," with a clear center and a red edge. EM can last for months or years. Only about 20% of people with Lyme disease get this rash.

Other body systems affected by Lyme-like Disease. More common than the rash are symptoms affecting the nervous system, heart, muscles, and joints. These can start weeks or months after the tick bite. Early symptoms might include flu-like illness, fever, headache, sore throat, tiredness, and aching muscles and joints. More serious problems can include swelling of joints, and heart problems. Lyme disease can be hard to tell apart from other illnesses like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome because the symptoms can be similar. If you have symptoms that could be Lyme disease, even if you don't remember a tick bite, see your doctor.

Treatment of Lyme-like Disease. Early treatment with antibiotics is important to prevent more serious problems. Pregnant women bitten by a tick should see their doctor.

Viral diseases

So far, no viruses have been found in Ixodes holocyclus. But it's possible they could be found in the future.

Protozoal diseases

So far, no protozoa (tiny single-celled organisms) have been found in Ixodes holocyclus. But it's possible they could be found in the future.

See also

In Spanish: Ixodes holocyclus para niños

In Spanish: Ixodes holocyclus para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |